A Future End to the Techno Religion

A half century into the digital frontier, the ground moves again

It’s tense. That’s the overwhelming mood in 2022, thirty years after the “rave” revolution began. It’s also been over a year since I posted here on Ghost Deep. Disruption is no longer the mantra of Silicon Valley but the mixed outcome across the planet. Electronic music, house, techno, EDM, whatever one wants to call it, was the sonic precognition of the digital age, and for those who were there to hear it, and if you were lucky enough, dance to it — long before the massive music festivals, and their pop conquests — it’s safe to say things haven’t turned out as expected.

Why? It seems disappointingly clichéd to write, but we all know, and I would argue many of us knew, that history can’t simply be outdone or outrun. There was and sometimes still is the exciting sense that we are surfing the waves of change. Technology offers so many possibilities. It is thrilling. It is dizzying. When the electronic music revolution began, it was that excitement one could hear in synthesized chords and machine beats that said “Go!”

Which in a way is kind of funny because maybe Doug Liman had it right more than Danny Boyle did, at least it seems from this Californian’s vantage. I know, many of us probably remember Boyle’s Trainspotting more than Liman’s Go, and yet the latter has grown as a 1990s cult classic in its own right. Following his 1996 hit Swingers, Liman’s 1999 Los Angeles rave comedy was written off by some critics as a Quentin Tarantino copycat. But that misses the mark. Go didn’t kill its way into minds and hearts. It floated like a Bruce Lee soliloquy.

“It’s like, ‘Hey man! How’s the ground down there?’" So says a raver to Go’s lead characters Ronna and Claire in a van outside a warehouse party, believing he’s high on what is fake ecstasy. Looking back now, it’s the film’s comment on the universal search for the spiritual. The truth is, Trainspotting maybe elevated heroin — and more than it celebrated ecstasy — the latter proposed as a salve to kicking the smack habit; Pulp Fiction on the other hand was homicidal mania, riding a heroin high of rock ‘n’ roll, a film that dared audiences to laugh at a poor kid’s head exploding at the end of John Travolta’s pistol point-blank. One semi-glorified drug use. The other clearly glorified violence. In contrast, Go, which was written by John August, was a more humane document, and ultimately the deeper, more sustained laugh.

It was somewhere between Fiction and Trainspotting, yet more immersed in the low cost seedy ways of LA’s nightlife and youth’s fascination with living the ultra life — its soundtrack lacked Trainspotting’s brilliant edge, but it also imbibed in the electronica rhythms and breakbeat flows throughout its winding, fracturing narrative that were its soundtrack to the underground. Its more astonishing magic trick however, was how it captured today more than yesterday. Mixed up, sexed up, stoned, and lost, its diverse group of heroines and heroes indexed heavily toward equality and diversity — faced with criminality, faced with consequences, the impulse at the end of the century, a decade before Barack Obama’s presidency, was “Go! Go! Go!”

So we did, and we have. We did go. We are going. But where? The things we took for granted are now up for debate: democracy, decency, dignity. Truth be told, I would have added “reality” to that list, but that would be disingenuous. There I personally have revised my own interpretation of the past and what resides in memory. No. Factually speaking, most ravers I knew, including myself, were eager to debate fundamental tenants of reality. Rave, above all else, was hallucinatory.

We were a ragtag band of renegade philosophers. Nihilists. I don’t write that word lightly. Often associated with the German philologist, philosopher and tortured soul, Friedrich Nietzsche, nihilism is one of those words that most people pick at gingerly, as if it were radioactive. Before it had the “nihilism” label — based on the Latin nihil for “nothing at all” — the Buddha described it as a spiritual orientation, in which we throw our hands up in disinterest and despair at the meaninglessness of life. I am not saying that “ravers” and the techno-enchanted are nihilists, but that there is a powerful strain of nihilism in the futurist mentality, because much of it stems relentlessly from a deep dissatisfaction with the past and the present.

And yet that is only part of the picture, because many ravers were also hippies. Zippies. That was what some U.K. observers dubbed the “new age travelers” that formed part of the ranks of the “Acid House” or “Ecstasy” generation that “saw the light” or “heard the future” in the late 1980s and early 1990s in grassy fields and dark warehouses, embracing the social liberation at the heart of rave’s artistic fire. The intense fascination with the “spiritual” among many early ravers pulled in the Goa trance of India and the rhythmic mysticism of Africa. Just like the hippies of the psychedelic 1960s, the ravers of the 1990s were drawn to fantasy, ecology, pharmacology and science.

These two ends of a spiritual spectrum are part of a tension that has emerged in the mass cultural waves of the 2010s and 2020s. Hedonism is perhaps where the two meet, from the disaffected to the earnest, converging in a cybernetic synthesis of circuits, cells and code, forming an interconnected system of electricity — as we migrated more and more from analog means to digital metamorphoses, caught between the tactile thrills of turntables and speaker cables, and the expansive “metaverse” that computer screens and sequencing software predicted, we overlooked the persistence of one immutably critical factor — human folly.

Hedonists. “One who regards pleasure as the chief goal of life.” Or at least those who put pleasure as the highest goal. Nihilists, it is said, more easily substitute pleasure for meaning. And the Zippies — the techno hippies, the lotus-eaters, the free spirits, the global experimentalists — found succor and fellowship in the hearty deconstruction and rejection of conformist capitalism. “Rave” was a new rebellion — dancing and hacking, experimenting and dosing, exploring and roaming. Technology, as ravers deemed — both chemical and instrumental — promised an instantaneous zap or groove into a more open, more colorful, and more exciting world.

Time was both faster and slower. The more everything accelerated through the zip of ones and zeroes, on and off, the pulse of electricity through the integrated circuits that became motherboards and microchips, from mainframes to desktops to phones, the more we seemed to be living in the mythic. Central to the urgent questioning was the search — which in a way found its purest expression in Google’s search bar — the quest for meaning, and behind that, what the Buddha in Sanskrit would call taṇhā, or desire, and what Nietzsche would call the Will to Power.

Yet it was not to me a selfish search, at least not in the beginning. There was the search for community, for commonality. We live in a time of backlash against cultural synthesis, a backlash to immigration, a backlash to miscegenation, and a backlash to multiculturalism — the accusations between the “woke” and the “anti-woke.” But the dawning of a global network of humanity — the Internet — was in many ways prefigured by the global wave of rave. For decades, it gave many hope.

In 1999, I wrote a 200-page thesis about the impact of electronic and digital technology on art, media and culture. The pretentiousness of that work was I hope balanced by sincerity. It was the outcome of five years of serious meditation on the potential of rave culture and the religious fervor I heard in its music and saw in its adherents. I have a vivid memory of taking my Brazilian friend Lucas Fortini — an ecologist and geologist nowadays — to a Moontribe in the Mojave desert in the summer of 1994; and him watching from the side of the dance floor, confused, perturbed even, at the “animal” dance moves of its “Full Moon” disciples.

Let go. Let the rhythm take you. Let the algorithm take you — and yet, in retrospect, risk losing control. Twenty years after the big bang of rave somewhere in the swamps of social media, witnessing the dissolution of friendships and basic common decency — my faith in the future — an optimism over technology’s empowerment of the hidden talents of the masses — was finally shaken. Lucas was actually onto something. I was naïve. Or at least, I have come to understand that the techno revolution was perilous. My stubborn faith in the good of ravers has clashed against those who have cheered authoritarians, or those taken with conspiracy theories about mass shootings. I still have compassion for the misled, but I cannot ignore the ebb of reason. For techno coincided with a rise of the paranoid style, that has led to violence and dissolution.

It’s easy to say what fools we techno-enthusiasts were, given today’s proliferation of paranoia on the worldwide web. It turned out all that connection also meant getting mixed up in each others’ ignorances, every one of us dragged into the mud. It’s not that I didn’t see the darkness. In my 1999 thesis, titled Pan and the Cyborg — the hybrid goat-man dancing with the hybrid cyber-man — its core theme was that humans are as irrational as we are rational and that the “animal” hedonism and hallucinatory visions surging through 1990s techno art embodied this tension.

Even so, I was not prepared for the gut-punch that the last 10 years would bring. Just as electronic music became as popular as ever, so the world seems to be teetering on the brink of disaster: climate change, Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine, the storming of the US Capitol on Jan. 6, 2020, the military signals of China to “take back” Taiwan, the raw divisions over gender identity, the woke-anti-woke metadata tagged tribalism, the tolerance among tech companies for the uglier sides of human nature in the name of free speech ruled by corporate algorithms and the almighty advertising dollar.

Whatever you dream, whatever you want. Here’s the thing. I’m not here to wallow in despair or claim I am ashamed of my raver days. In fact, I am nowadays more upbeat about the future than I have been in a long time. It’s just I am in no hurry to get to the future any more. The future is here, and in many ways, it’s not that great. But it also isn’t hopeless or without its signs of progress. It was silly for us partisans of the techno religion to think human nature could be quarantined in the 21st century.

Wisdom in rhythm is simply how the universe works, I’ve come to believe. I can’t prove it, but then again, the historical evidence is rather convincing. Over the last 12 months I have spent much more energy on my creative writing and Ghost Deep’s sister blog, Wraith Land, which was originally conceived as a forum to explore the warping and “wraithing” caused by algorithmic communications i.e. social media; and also how mythology had not only grown as today’s entertainment bent, but perhaps a last common ground for human connection and understanding.

The more I write and meditate on what J.R.R. Tolkien called Faerie, however, the more these two sides of the same coin — one focused on technology and one focused on mythology — converge. Like many writers, I am engaged both with the past and the future, and very much through the fiery lens of the present, and vice versa. This waywardness is due in part to my own restlessness as a storyteller.

I do not see myself as a journalist. I do not see myself as a fantasist. I see myself simply as a writer. It is my duty, I feel, to translate what I have experienced, learned, and understood, into words and images, a communion between you and me and the universe. Rave was something I had the privilege to experience — early enough that it came to me almost as if it were a child, and late enough that I did not birth it — hence I am both engaged and removed. Myth was something I had the privilege to experience as a child late enough in its evolution that it came to me as truth, and late enough that Tolkien had perfected it as an art form that could speak to timelessness, and critical awareness, after the rise of the machines and not in the form of a religion.

I have another distinct memory riding in the back of a van to Moontribe listening to one of my older brother’s mixtapes — my brother DJ John Kelley had quickly become the second resident DJ of Moontribe, the breakbeat Yang to DJ Daniel Chavez’s trance Yin. On that drive at the end of the tape, came the techno riffs of React 2 Rhythm’s ‘Whatever You Dream (Dark Mix),’ yo-yoing up through the octaves; its propulsive polyrhythms scaling a kind of cyber mountain of psychedelic delirium — a voice repeating “Whatever you want, whatever you dream” … off into the ecstatic.

“Not all who wander are lost.” Anyone familiar with wizards will know the aphorism. Both Tolkien and Nietzsche, who did not live to see the Digital Revolution — and lived closer to the big bang of the Industrial Revolution — were confronted in their own time by a crisis of nihilism. While Tolkien created a modern mythology, that would appeal to kids in a secular modern world, bestowing a sense of awe at the universe and a clever kind of restoration of “God” to the center of our moral compass, Nietzsche in contrast celebrated the “death of God,” and from there tried to draw a new map for the affirmation of life and its glories. Those two legacies still live with us today.

I’m not one to declare myself as living in only one tribe or the other. As a mixed race individual — and let’s face it, we’re all ultimately mixed race, or one race, when we all do the honorable thing and trace our deceptively disparate stories back to Africa — it is inherently self-negating to wear just one pair of dancing shoes. More interesting, is to follow their example, and unpack the semantics of any question. Don’t take a word for granted, ever. Hedonistic is what critics called rave culture. While I recognize that indeed for many, and I will allow, most people, went and go to raves to get high, for myself, that was never my thing. If anything, I find the chemical path to an instant enlightenment fairly shortsighted, though I try not to judge anyone for it, and I acknowledge the powerful therapeutic applications of some psychedelics.

“Hedonism” is based on the Greek word for “sweet” — hēdys. That stem or source word is related to the Latin sauvis, and the Sanskrit svadis. And Sanskrit is the ancient Indian language of the Hindu Rig Vedas, wherein mystics wrote praising verses to the mind-altering or soul-opening concoction of soma. You might think I digress, but that is the point. Language evolves. Writing weaves, as the recording and manipulation of speech. Music evolves. Composing music with machines bewilders, as the recording and transformation of sound. Music and language embody change, and can open us to sweet-ness. So how do we renew sweet reason in this disembodying meta-world, without bitter-ness, soma-less? Not to lose the bitter-sweet, but to keep both in a more constructive and humanizing balance. Not order. Not chaos. But resilience.

Machines have transformed writing. After over 30 years of writing with computers, there is no shadow of a doubt in my mind that this is true. The ability to publish words to a blog or a network of newsletters — Substack — is itself a challenge to the purity and more fixed authority of the book, and the magazine, and the newspaper. We all know this as part of today’s media landscape. Choice is now vertiginous. And yet books still command greater respect. Why? In part, it’s because they too wander within many pages as they strive to transport us far outside of time.

About six years ago, I was asked to help consult on the autobiography of Pasquale Rotella, the “rave king” of EDM, the mastermind behind the Electric Daisy Carnival. It was a unique chance to map out the all-too-human side of the rave myth. At the same time, Ghost Deep was my sketchpad and conduit for my personal observations. The vision for any worthy history of rave culture had to be authentic. Its first incarnation was the Museum of Lost Tales. The second, Electrohound. Then “Ghost Deep” was envisioned as a step back from ego while also representing a recommitment to the truth of “rave” — the ghost in the dance — a tale with complex global and technological dimensions and implications.

And yet in 2018, I was asked to help someone else produce a documentary about the Los Angeles rave scene. Originally it was pitched to me as doing something like an art film with some history layered in, an emphasis put on the audio-visual potential of electronic music. As we discussed the filmic possibilities, I began to bring forward concepts and ideas I had long nurtured, going back to Pan and the Cyborg. Still, I realized over time that it was more art, than history, and while any history of rave presupposes the potential for a mesmerizing telling, the truth needs little.

With that, I decided to step away almost completely from such ambitions. But in 2021, another friend asked me to help do a very different documentary. In all of these cases, they had come to me, and the first two put me at odds with where I felt I needed to go. But this third time, focusing on the history of breakbeat techno, felt better.

To be honest, electronic music culture in many ways is lost on me these days. Not because I don’t understand the music but because finally the story is at a truly new inflection point. With the “death of tech” to my mind, so the “death of rave,” though we all know that rave will keep bouncing back like some zombie god.

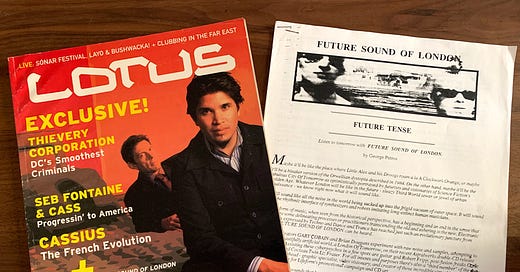

I jest darkly: maybe it’s not a zombie god, but a mixed blessing. It’s a wandering god, a dazzling muse. Leafing through my rave magazines, I recently picked up some of my old Lotus articles, in particular one on the Future Sound of London. I wrote it in 2002, twenty years ago, a year after 9/11, the last time I stepped back.

Garry “Gaz” Cobain of FSOL, nailed it: by 2001, we were already in danger of becoming too robotic. Another article, ten years before mine, I found on the Internet in 1996, where the interviewer George Petros described their music as conjuring robots playing music in a world where humanity has gone extinct. Petros saw it.

In many ways, it’s fitting. Spiritual searchers, FSOL bowed out of the rave “fairy tale” long ago to the consternation of many. Reading both stories now, however, it is clear to me that there is another side to the rave story that needed time to tell.

So, a documentary perhaps, and one day, perhaps a book. For now though, I am restarting my dispatches here along with my Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s. Go forward, then. Go!