A Guy Called Gerald - ’Black Secret Technology’

No. 26 in our Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s

“There’s so much color in it. So much rhythm. So much texture. You could go into a jungle and find these things. You could sit there in a pool in the middle of a jungle and there would be flowers, insects, dangerous animals, dangerous plants. But there would be a lot of beauty…” — A Guy Called Gerald, “Future Soul Jungle Revolution,” Chris Campion, Urb magazine, Summer 1995

“Gerald deep in the jungle” — that’s how the man who penned The Haçienda anthem ‘Voodoo Ray’ saw himself by the mid-1990s. He was apart and on a solemn mission. Long gone were the acid house rhythms and joyous melodies of his earlier career. Instead he travelled the primal tribal jungle of Rage, dilating time into illumination. Following his seminal drum ‘n’ bass album, 28 Gun Bad Boy, A Guy Called Gerald continued to push his distinctive style deep through the forest of time; with Black Secret Technology, Gerald hacked his way right into a vast new continent of time.

Hugely influential, 28 Gun Bad Boy had hacked a path into the jungle — what critic Peter Schapiro had described as “a flurry of gun-play beats and rude bwoy swagger.” Beyond its defiant attitude, what separated Gerald’s “artcore” statement from others’ showmanship was its raw technical ease within a gritty production patina. Through its audio haze — a result of Gerald’s preference for older analog gear and sequencers — his deft acid house hand sliced through time, cutting beats up and restitching them into a new kind of cybernetic relativity. That razor sharp philosophy put complex, understated, and yet hypnotic rhythms, right at the forefront of the dance floor.

“Originally, I was into drum machines,” he told Melody Maker in 1995. “I used to hate breaks. But then, I discovered that with a sampler you don’t just have to take a break and loop it, you can chop it up into segments, recombine it, enhance and stretch the sounds. Basically, you can turn a couple of hits into a whole drum solo.” Released on his own Juice Box label, 28 Gun Bad Boy was a collection of lonely and grimy proto-jungle, evoking Manchester’s wet and dangerous streets, and folding into London’s hardcore underbelly — it mixed acid house with rough hip hop on tracks like ‘Got A Feeling’ and channeled gangster brio on ‘Money Honey.’ On the seventeen-minute intro ‘Mix,’ Gerald kicked open the doors with gunfire samples and racing rhythms, blasting and blazing with the drum ‘n’ bass movement’s most assured manifesto.

Jungle was an idea. Not just a place or a music genre. It was born out of the deep tensions and trials of British class and racial discord. Arrhythmic cultural patterns rose especially out of the fractured experience of African-descent Brits — many of whom had come to England from Jamaica and the former slave colonies of the Caribbean; Gerald Simpson came from Manchester’s mix of industrial decay and immigrant ferment, from Afro-Caribbean, South Asian and even Irish displacement, in neighborhoods like Moss Side, Ardwick, Hulme, Rusholme and Cheetham.

In fact, Manchester was one of the main centers of the diasporic Windrush Generation, the large Afro-Caribbean immigration wave from the late 1940s to the early 1970s, which first came on the HMT Empire Windrush. London, Birmingham, and Bristol were also important urban hubs of the Windrush Generation, who not only had to face massive migration changes in terms of identity and opportunity but also racial discriminations in their new English home. Mixmag’s Bethan Cole captured some of Gerald’s own fractured experience in 1995, describing how his father was a rubber molder at a Dunlop factory and his mother a nurse, but who then divorced when Gerald was five, forcing his family to leave Moss Side and then return later to Rusholme when he was eight, further breaking his childhood into fragments.

“They put us in a home because I wouldn’t attend school,” Gerald told Mixmag, explaining how he and his brother would get into trouble. “We were terrorists and I don’t mean like little things. We used to rob cars and set fire to things.” But in time, they channeled their fragmentation into music by setting up a sound system in their mother’s attic. “We had two 18 inch speakers,” he recalled. “On top of that we had a pair of 15 inch speakers, on top of them we had a pair of 12 inch speakers and on top of them airhorns. There was an amp, decks and the records I used to play. Everything was stolen. Even the wood for the speakers was robbed from a building site.”

So desperation became inspiration as Gerald fell in love with sound and music. He picked up on new rhythms, listening to the groove-heavy funk and the Northern Soul played by Mike Shaft on Manchester’s Piccadilly Radio, which echoed throughout the northwest of England. Northern Soul was a uniquely Northern England music culture, prizing American soul and rare groove records from labels like Ric-Tic Records and Tamla, often played switched up to 125-140 BPM speeds. Eventually, Gerald also discovered the jazz-electronic sounds of Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock too.*

His favorite record of all time was Tap Step, by Corea. Graham Massey, who would later form 808 State with him, recalled how Gerald “used to go to Longsight Library like myself and borrow the records. He used to come back with Chick Corea L.P.’s, and we’d share things like Tania Maria L.P.’s. So in the period when we first got together as a group, under the guise of dance music, we were listening to a lot of ‘70s stuff really.” The song ‘The Slide’ from Tap Step was Gerald’s template, an endlessly changing, billowing, warping and surprising twist through a percussive and melodic storm.

It’s here that Gerald’s vision of jungle finds its flashes of lightning and its distant thunder. Its percussive and even militant jazz-fusion syncopation, as Cole observed, was the electrical charge that arguably formed the initial crystallization of his unique soulful, musical DNA, simultaneously spiraling inward and outward at all times, his sense of groove winding deep down into a shared past, present, and future. In an “Invisible Jukebox” feature on Gerald for The Wire, Massey could easily pick out Gerald’s jungle rethink of ‘Voodoo Ray’ — ‘Voodoo Rage’ — in about 15 seconds.

It was voodoo in a tempest. Jungle, Gerald’s jungle, was about the purest self-expression one might achieve through drums and melodies. “The great thing about Gerald is that he’s completely autonomous,” Massey told The Wire. “He lives in Gerald world. No industry person could ever get near him or deal with him because it was too much hassle. You could do a great Jackson Five type cartoon of Gerald in Gerald world.” Massey had put his finger on the invisible pulse at the heart of Gerald. Surrealistically, “Gerald world” was not a cartoon, but as real as real can get.

“When Gerald made ‘Voodoo Ray,’ he was living in a squat, conducting phone interviews from a call box and still working in McDonald’s,” Cole reported. “You’d see him walking around Hulme on TV documentaries. The classic stuff of Manchester mythology.” Hulme, the home of brutalist Manchester housing estates and tower blocks, like Hulme Crescents, the vast quadruple arcs of soul-crushing urban architecture — the largest public housing project in Europe at the time — and sheltering over 13,000 people, was a symbol of Manchester’s rotting heart.

And yet in that urban jungle, Gerald found the light. He struck fire. Or as he told American journalist Chris Campion for Urb magazine in 1995, he was using a Roland SH-101 synthesizer to try to make Detroit techno, much of its early sound developed on Korg D50 synthesizers by Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson: “I was trying to mimic them. I didn’t have the technology so it was coming out wrong, but it was a good wrong, if you know what I mean.” The classic SH-101 xylophonic notes spiraled down in a Corea-like coruscation, and yet a hypnotic swirl from another otherworldly dimension, not jazz fusion, but rave revolution. In and within. Out, freakout. Acid’s forever horizon — Nicola Collier’s sweet cries a shining dawn.

In the years leading up to that dawn, Gerald was constantly experimenting. He collaborated with Nicky Lockett (MC Tunes), and the brothers Anderson and Carson Hinds before they formed The Ruthless Rap Assassins, jamming on the sound system he had set up in his mother’s attic — Attic Studios. “Sundays were hip hop only days,” recounted Cole. “The rest of the week Gerald would mess around on the 303 he had picked up and heard on Ice-T records.” The Roland TB-303 — the “303” — was the sound of acid that Gerald twirled around his SH-101 marimba magic, cascading its bass line to its climbing wails of bliss on ‘Voodoo Ray,’ transforming the nature of Manchester overnight — a spilling out of pain — bringing light into the darkness.

The Windrush legacy of Hulme, Rusholme and Moss Side, found its most famous expression in ‘Voodoo Ray,’ but not necessarily its liberation. The hip hop of Ruthless Rap Assassins on their album, Killer, with its classic ‘And It Wasn’t A Dream,’ was later considered UK hip hop’s finest hour, setting the stage for grime. But as the journalist Ophira Gottlieb documented for The Mill, the London music scene’s indifference to Mancunian hip hop, amateurism, and racism, greatly muted its breakbeat impact. Instead, Gerald, who had been critical in that scene’s genesis, would find greater cultural success with his acid house music — a voodoo trick of epic proportions.

In his work with 808 State, he helped write the album Newbuild, which became a major influence on Aphex Twin. Released in 1988, it featured acid warps like ‘Flow Coma’ and ‘Narcossa.’ As A Guy Called Gerald, after the sensation of ‘Voodoo Ray’ on Rham! Records, he wrote the euphoric album Hot Lemonade, released in 1989 and another Aphex Twin favorite, filled with cosmic classics like the title opener, ‘Hot Lemonade,’ ‘Rhythm of Life,’ and ‘Tranquility On Phobos.’ Signing on with CBS Records, however, he ran into major label pressures and constraints, 1990’s Automanikk defiantly kicking it with gorgeous gems like ‘I Feel Rhythm’ and ‘Subscape.’ A fast tempo album, it was Gerald world to Sony’s chagrin.**

He would not bend as his soulful song ‘I Won’t Give In’ declared. And yet, commercialist demands on his artistic instincts pushed Gerald to the breaking point. Partly inspired by Frankie Bones’ breakbeat-house series, Bones Breaks, he played ‘Voodoo Ray’ over a “tearing drum and bass percussive” in New York, as Mixmag described it, pushing his ‘Voodoo Ray Americas’ version to heady new heights. Returning to England, energized, he switched gears to ‘28 Gun Bad Boy,’ his reinvention moment, released on a 1991 white label, his last trip for Sony.

“Jungle is a feeling of frustration and trying to fight your way out,” he told i-D magazine’s Kodwo Eshun. “As I hear it, it’s a mixture of things. It’s like going into a tropical rainforest. But then, there’s a lot of aggression and tension in the music as well. It’s like fighting your way out of something. I’ve had people pull shooters in my face here in Manchester. They want to shoot you down if you’re doing something for yourself, and that’s what comes across in my music now.”

It was like a gun in your face. The beats flying like bullets. The bass tugging like the recoil of gunfire on a gun barrel. ‘28 Gun Bad Boy’ was bad. The violence of it was a revelation in 1991, but its inner calm, the vast space in its torrents, turned all of that Windrush arrhythmia into a new rhythm — a rhythm made of many rhythms. Cops, Gerald’s third release on his own Juice Box label, was the white label made official. Presaged by two other E.P.’s, his Digital Bad Boy and XtRO’s Toys, it kicked off his complete break with major labels and mainstream preoccupations.

Composing the songs that would go into the album 28 Gun Bad Boy’s intro ‘Mix,’ a storm of singles and tracks followed in rapid succession, including the ragga vibes of ‘Ses Makes You Wise,’ the ricocheting funk of ‘King of the Jungle,’ the chant-down Babylon boo-yah of ‘Free Africa’ — “We gotta free dem in da jungle!” — and the wheezy, spidery ‘Anything.’ The writer Simon Reynolds — who made jungle his preferred topic in the mid-‘90s — took great pleasure in the insanely acrobatic wordplay that describing Gerald’s drum ‘n’ bass music could invite…

The song ‘Darker Than I Should Be’ was “languid, 21st Century jazz funk,” wrote Reynolds for The Wire in 1994, for a feature titled “Above the Treeline.” ‘Gloc’ sounded like “struggling through the Cubist vegetation of a planet whose lifeforms are based on silicon rather than carbon.” And ‘Nazinji-Zaka’ was “a cyber-juju barrage of poly, cross and counter rhythms that pull your body every which way, while pizzicato sound-shapes dart like birds through the digital foliage.” Birds and bullets and beats.

For Melody Maker, the same year, Reynolds gave a nice succinct inversion to mainstream assumptions about jungle music: “The complexity is rhythmic rather than melodic. Or, rather, the rhythm IS the melody. Gerald's tracks take the jungle mesh of polyrhythms, cross-rhythms and counter-rhythms to new levels of insane detail.” Ah yes, “poly,” “cross” and “counter” looped across the pages. While most latched onto jungle’s fractured and seemingly chaotic percussive nature, it was in fact still a very organized structure, its breaks looping and repeating in a rolling, hypnotic trance.

As Gerald explained to the journalist Chris Sharp, his attraction and fascination was bound up with the parallel interchanges between different timelines but in a way that everyone experienced in the world — so that what he created was the inter-phasing of different but kindred worlds: “You know if you’re on a train, and you look right near the track everything’s, like, going mad — but if you look further back, at the trees, they’re sailing past. That’s what I try to create with the stuff that I do — there’s always a fast thing that you can latch on to, and a slow, dreamy thing, too.”

Its secret technique was cyber-black. While his music was universal, it also came from his distinctly Black British experience. “There’s a real mish-mash of music here,” Gerald explained to Vox’s Stephen Dalton of Black Secret Technology. “Jungle is just a whole cross-section of what’s happening in Britain — like, my parents were Jamaican and I grew up Jamaican in Britain. That does your head in a bit but it can also work to your advantage, listening to different influences and mapping out your own plan.”

It was as if he was on that train, looking out, looking forward, looking back. Except Gerald’s train was unique to him, shared with other Windrush descendants, and then taking in Manchester, London, England and beyond. “I’d be listening to Detroit techno in my bedroom,” he told Dalton of his experiential phasing, “then I’d go downstairs and my brother would be playing Shabba Ranks, then I’d go out and hear house music and jazz. So you end up mixing different sorts of music unconsciously.”

That was the Black and British part of Gerald. But there was also the cyber side. Seemingly left to his own devices, he developed a love of machines and the sounds they made from a very early age. From his sound system construction to an obsession with sequencers, drum machines and synthesizers, he was drawn to how they ticked. Nothing was spared his deep curiosity. “I got a toy tank for Christmas and it played a tune, and I just had to know how it worked,” he recalled for Reynolds. “I took a knife but I couldn’t get these mad screws to open. So I heated the knife in the oven and sliced through the plastic, and ripped the tape recorder out. I just had to know.”

Which is a great window into Gerald’s psyche. He had to know. Where did it all emanate from, the migrations, the rhythms, the drums? In 1995, on the eve of Black Secret Technology’s release, he talked to Urb magazine about where the album’s title came from. “I was watching this show, a late night TV chat show,” he told Campion, “and there was this totally mad woman on it and she was going on about the government using black secret technology to brainwash people.”

“I thought it had a nice ring to it,” he continued. “I thought that kind of angle, technologically, is where the old media system is coming from. Everything that is out there commercially has some kind of brainwashing technique or something within it. So [the album is] basically a form of expression to say, ‘Yeah, look we know where you’re coming from, and we’re not gonna be derailed from our missions.’”

Out of hardship, came worship. The madwoman’s superstition fit. After Sony cancelled their contract with Gerald, refusing to release his follow-up to Automanikk — High Life, Low Profile — Gerald parallel processed 28 Gun Bad Boy, making it under deprivation and duress. His studio raided in Manchester, he was piecing together a new future for himself when he got a call from Goldie down in London. The colorful ambassador and co-inventor of drum ‘n’ bass wanted Gerald to come to Rage.

“I was living in a house with no heating, it was freezing,” he told Campion of his Manchester life post-Automanikk. “I’d go into the studio and have to turn everything on and work to keep warm.” But in London at Rage — the legendary hardcore and drum ‘n’ bass club night helmed by DJs Grooverider and Fabio — Gerald found a blistering, burning hot world that warmed his whole being. Gerald had found his jungle, not just his world; jungle in London and Manchester formed an alliance.

“In Manchester there were a lot of people saying it was ‘rave music’ and they were getting out of that because after things like ‘Charly’ for them it was like ‘sweaty rave,’” he told New Musical Express, “but I knew that there was something there and I just kept me head down and kept at it. And then one day I got a phone call from Goldie saying come down. I didn’t know anything because I was up in Manchester. I was summoned down to Rage at Heaven.”

It was at Rage where Gerald got to hear the collisions of his intuitions. For The Prodigy’s ‘Charly’ had signaled a schism in the London underground, where more breakbeat-fueled “hardcore” techno and house music — undergirded by both the soul, funk, rock and hip hop legacies across the Atlantic and their translations in England, and the upwelling bass legacies of reggae and dub from Jamaica and Windrush generations — syncopated with hints of progressive elements too, including the otherworldliness of Future Sound of London’s ‘Papua New Guinea.’

“I was listening to everything from street soul to ‘Papua New Guinea’, the really early breakbeat styles,” Gerald told the NME. “With Black Secret Technology, there is a lot of inspiration there from people like 4 Hero and Goldie as well. It’s weird because that sort of came out of what I was doing years ago and they took it to a new phase. So I’m being inspired by something that was inspired by what I was doing years ago.”

Released in 1995, Black Secret Technology was an explosion of creative energies. Filled with ghostly vocals and electric paranoia, A Guy Called Gerald’s second jungle album is deeply nocturnal — a phantasmagoric loop through swampy ambience and streetwise drums. The greatest joy of Black Secret Technology is its dreamy beauty, accentuated by its disorienting rhythms and psychedelic flashes of light. Lost in a hallucinatory fever, it sometimes evokes a dreamlike sonic vision, of a Dickensian underworld, caught between city and country, equal parts Oliver Twist and Artful Dodger. An artful twist into ecstasy, ‘Voodoo Ray’ had been a breakthrough for Britain’s electronic identity. But now rave faced the shortcomings in its vision.

For Black Secret Technology, as typified by Gerald’s utter transformation of his ‘Voodoo Ray’ rave anthem into ‘Voodoo Rage,’ was an artful twist in almost the other direction, into the aftermath of that communal dream and all of its expectations. Both Rage the club and rage the emotion that found some of its expression in the hardcore rave scene and its musical mutations, marked a new destination. For it was Gerald’s destiny, it seemed, to push rhythm itself into entirely new contemplations, about Western society, its use of technology, and the very long dream of freedom.***

The wrinkles in time are many in Gerald’s journey. While the original release of Black Secret Technology was beloved by the drum ‘n’ bass faithful, nonetheless it did not have the reach Gerald hoped for. As a result, a year after its release, in 1996, he re-released it with a different track listing and order. The original started with the soul song ‘So Many Dreams’ — a more plaintive opener, filled with haunting call and response vocalizations and tribal drum patterns — and a murkier sound; while remastering on the 1996 version and a new starter opened a parallel universe.

Equally important was a new clash of urban and natural vectors. It drips with the modern and aches with the primordial. Starter ‘Hekkle And Koch,’ a sly reference to weapons maker Heckler & Koch, ducks and scurries in an alley gun fight, its battling drums exchanging rapid fire. On ‘Alita’s Dream,’ watery synths flow above and below crunching beats, the distant calls of vultures and trumpets placing the listener in a fertile shadow-land. Aquatic wood-tone rhythms churn under sensual chanting on ‘The Nile,’ a riverboat drift into the delirium of East Africa’s many chambered heart calling to mind the Nubian desert and its mighty lake-filled highlands.

Driving the album’s centrifugal force is its diced up beats, spurting electric currents through the mind or casting the spell of a fireworks show. Once again, Urb’s Campion captured Gerald’s drum ‘n’ bass aesthetic, as “snapshots that defy time propelled by the chronographic motion of constantly revolving beats.” It’s that constantly smooth flow of time, punctuated by Gerald’s percussive constellations, that made him a standout in Britain’s highly original drum ‘n’ bass innovations.

Key artists like London’s Goldie and LTJ Bukem would sharp-shoot with their laser-guided beats and jazzy atmospheres. Photek would transform deconstructed rhythms into a martial art. Roni Size would crack the commercial ceiling with a Mercury Prize. Ed Rush & Optical would bring banging metal to the party. But only A Guy Called Gerald convincingly delivered music across Britain’s whole rave spectrum. Take exemplar ‘Finley’s Rainbow’ — “Make me wanna move” — a love ballad fit for a morning DJ set and love at first sight, “a vocal track carried by strings,” wrote Mixmag’s Cole, “which curve off over the ends of the earth…”

‘Finley’s Rainbow’ beautifully channeled the reggae soul of his West Indian roots. Tapping the then unknown Finley Quaye on vocals, it coos to rock steady rhythms and loving synths. Clouds breaking high overhead, a glimmer of sunlight shines through a thunderstorm as Quaye earnestly echoes Bob Marley‘s ‘Sun Is Shining.’ Elsewhere, the sultry gasps and trills of ‘Silent Cry’ and ‘Energy’ inject a feminine mystique, quieting the album’s edgy prowl deep into the lonely wilderness. Like ‘Finley’s Rainbow,’ they circle and open and cry with a ghost that is human to the core.

What comes down, must go up. In early 1995, the NME’s Roger Morton took a freight elevator up 18 floors to Goldie’s studio and digs in a London tower block. “It’s mid-morning round at Goldie’s concrete perch,” he wrote. “The window at the end of Goldie’s living room looks out over a cityscape, which the two of them are helping to re-define.” The “two” were Goldie and Gerald — the Two G’s, as it were.

‘Energy’ was a collaboration between the two. “I remember Gerald from before he remembers me because he’s like our hero. I remember hearing ‘Voodoo Ray’ in the background and my mates were like dropping acid and I was like ‘What’s all this?’ The next encounter was hearing Fabio play his stuff at Heaven, when breakbeat first kind of came in … For me it meant that it had gone full circle because it was people like Fabio who were playing Gerald in early acid days.”

Talking to The Wire’s Julie Taraska a year later, she played for him ‘Automanikk,’ testing his knowledge of Gerald. He got it in 30 seconds — “We all listened to Gerald,” he told Taraska. “We are all windows and mirrors, we reflect around each other: all catch the light at the right angle; keep spinning around. No one person can say they started jungle, but everyone can say they contributed to it.”

“Mind-waves, breaking down barriers and sound ...” says a voice on one of Black Secret Technology’s best secrets, the whirling, hurling, cycling ‘Cybergen,’ a voice perhaps of Gerald himself: “Cybergen! — a new kind of drug that'll take you up and down ... anywhere you wanna go ...” Deft drops of samples, like the hollering “Rock!” by Aretha Franklin from ‘Rock Steady,’ a little ditty from ‘Blanka’s Theme’ from Street Fighter II by video game composer Yoko Shimomura, and kicking drums from X-Men’s ‘Phase 2,’ disorient and uplift at the same time, the kind of mastery of sound and music dynamics that can re-ignite a dance floor, taking minds back up the tower.

So there they were, on top of the world, looking out from the 18th floor of Dorney Tower in North London, the constellations of the drum ‘n’ bass movement flickering in the city lights, sneaking in the night, its bursts of rhythms carving the sky. For drum ‘n’ bass was a kind of super polyrhythmic, cross-rhythmic, and counter-rhythmic time machine — traveling across cities, civilizations and over oceans — off into infinity. Tranquility of the jungle though was just as important to Gerald, the insects, the dangerous animals and plants, and the pool at the center.

“I was talking to an old drummer and he said that he was taught that the drum was the heart and the bass was the earth,” Gerald told The Wire’s Peter Schapiro. “That’s the foundation of nyabinghi drumming ... Black Secret Technology was an exploration of that, I was using some African rhythms and at the time I was exploring the Nubians and reading about the Pyramids … I believe that the first civilization will also be the last. I think that time is one big circle. Time is cyclical.”

“Say someone has created a drumbeat,“ Gerald explained. “They’ve done that in a space and time. If you take the end and put that at the start, or take what they’ve done in the middle, you’re playing with time. With a sample, you’ve taken time. It still has the same energy, but you can reverse it or prolong it. You can get totally wrapped up in it. You feel like you have turned time around.“

It’s this infinite possibility and time’s mysteries — and how drums and bass and rhythms and melodies — that can capture our attention or soothe us into deeper reflection, that make Black Secret Technology such a quintessential album. Even the album’s two alternate endings between its original 1995 and its 1996 remaster release express this alternate nature. ‘End of the Tunnel’ gives Miami Vice vibes while ‘Touch Me’ patiently plucks its strings as its drum ‘n’ bass rhythms fire with energy.

Jungle is more than an idea. The sweat and grind of raves is never far. The trampoline trance of ‘Cybergen’ rolls to a hypnotic riff, swaying up and down to wheezing drums and metallic kicks. Tripped the hell out, it seems to heave up a rogues’ gallery of inventive sonic tricks — sleight of hand for the transfixed ear. It’s in many ways Gerald’s greatest achievement, a mind dazzler jumping at the base of your skull. While the demented, eerie and clever ‘Survival’ and ‘The Reno’ call to mind Warp Records‘ Artificial Intelligence stable, as well as Future Sound of London‘s moody ISDN and Dead Cities phase, dark yet magical and infinite time maps unfold.

Another map spreads with ‘Cyberjazz,’ its skitter-scattering rhythms and echo-dynamics triangulating across the air like dragonflies, its tribal metallic drums skipping and splashing the water surface, its deep bass drums hinting at more secrets below; a meticulous groove that would be sampled two years later, by Underwolves, for their jazz-jungle classic ‘Malik,’ Gerald’s ‘Cyberjazz’ memorializes the album’s powerful, secret influence on future time-trippers. It samples the movie Robocop — “You’re going to be a bad motherfucker!” — mythologizing the cyber birth or resurrection inherent in humanity’s long journey from jungles through machines. As an astute YouTuber named “spatialkatana” later observed in 2022, “The guy cut the path through the woods, and they all followed.” It took mien, technique, and vision.

“Usually I’ll do the drums first and structure them in threes,” Gerald explained to Campion in 1999. “If you’re going to take it back to that tribal element, it’ll be mommy drum, daddy drum and baby drum. It’s all in that code … I think a lot of producers work on the computer and lock the beat … they think if it’s outside it won’t be in sync … but the way circular theory works, you can have a rhythm that drifts off slowly and comes back on. If you get that, you’ve almost got like a rocking movement. You’ve got to be able to abuse the sequencer. Sequential timing is not law.”

Eschewing the perfect clock of digital sequencers for his older transistor-based gear, which slipped in and out of phase — Gerald embraced nature’s accidental perfections, mirroring the relativities of human thought. The track ‘Life Unfolds Mysteries’ put this philosophy into soulful song. “Ever changing! Changing! Life unfolds mysteries of the day to day.” Its resonant, sweeping synth flows low into the solar plexus again and again. “Smoke on it.” Well, it doesn’t get franker than that.

“Methods of rhythm helped early man get in touch with the universe and his small part in it,” Gerald opines on the sleeve of Black Secret Technology, connecting the sharpest drum hits to the eternal cosmos. “He discovered some of the secrets of the rhythm of nature. I believe that some of these trance like rhythms reflect my frustration to know the truth about my ancestors who talked with drums.”

Using technology with a fidelity to the power of rhythm — the heartbeat, the orbits of the Sun and Moon, the electromagnetic pulse — it’s no surprise this Jamaican son of Manchester answered the call of the jungle.

Talking with his drums, looking into the pool in the middle of the night, hearing new rhythms in the trees, he helped tune our circuitry to our universal ancestry, turning broken time into the deepest of origins.

Track Listing to 1995 version:

1. So Many Dreams

2. Alita’s Dream

3. Finley’s Rainbow (Slow Motion Mix)

4. The Nile

5. Energy (Extended Mix)

6. Silent Cry (Gerico)

7. Dreaming of You

8. Survival

9. Cybergen

10. The Reno

11. Cyberjazz

12. Voodoo Rage

13. Life Unfolds His Mystery

14. End of the Tunnel

Track Listing to 1996 version:

1. Hekkle and Koch

2. So Many Dreams

3. Alita’s Dream

4. Finley’s Rainbow

5. The Nile

6. Energy

7. Silent Cry

8. Dreaming of You

9. Survival

10. Cybergen

11. The Reno

12. Cyberjazz

13. Life Unfolds Mysteries

14. Touch Me

*As Cole wrote, “He started combing Manchester's record shops to find albums by jazz funksters Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, fascinated by their avant-garde fusion of jazz and rock, drawn to the tense, militant edges of 70s syncopation.”

“Chick Corea was the first person I heard playing electronic synthesizers and stuff,” Gerald told Cole. "I was so intensely into it, all his stuff, I know it note for note."

“I liked the flavor I was getting from Chick Corea, he's really experimental, freeform, electronic, classical — there's loads of styles in there,” he told Jockey Slut. “From that lead, I dug deeper and got into some of his earlier stuff like 'Return to Forever' and various L.P.’s. I go for certain tracks, there’s one on the 'No Mystery' L.P. called 'Sophistifunk' that was like acid! Using all those keyboards and bass — acidy.”

“From there I got into Airto Maria which was just like percussion and Brazilian kind of stuff. I got more into my drum machine — it was just one of those little Roland things. I tried to get Brazilian sounds out of it when I used to jam."

In 1996, talking with Remix magazine, he talked some more about his admiration for Corea and other jazz artists like Miles Davis, Flora Purim and Azymuth in Brazil, and Japan’s Toshiyuki Honda.

And when it came to electronic music, he told Muzik in 1995: "I’d been into electronic music since the late Sixties. I was a big fan of people like Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream and later Emerson, Lake & Palmer.”

“I’d always dreamed of owning one of Keith Emerson's [Moog] IIIc,” he added, “which is basically how the ball started rolling.”

**It’s a little confusing, but ultimately Gerald was signed with Sony, the parent company of Columbia and CBS Records. His High Life, Low Profile, a second album for Sony, was ultimately rejected. Gerald refused to change course and instead chose to permanently part ways with Sony.

Interestingly, while many have associated A Guy Called Gerald primarily with jungle ever since his Juice Box and 28 Gun Bad Boy days, the kind of diverse music interests he displayed on his Sony albums would show up after Black Secret Technology, as he continued to experiment with house, techno and soul.

In 2000, five years after Black Secret Technology and four years after its remastered and expanded reissue, he released a future soul classic with Essence, including the beautiful ‘Beaches and Deserts.’ 2006’s Proto Acid / The Berlin Sessions marked a spirited return to his Mancunian acid house days, a brilliant seamless ride.

***As Gerald explained to Campion, “I got all the old samples out and started working on it. I got to the Voodoo Ray sample, and I forgot all about this but at the time when I put it into the sampler it was Voodoo Rage but because the sampler that I was using in those days didn’t have much memory it ended up as Voodoo Ray. So it chopped the G off, totally, just chopped it off. And I just forgot all about it.”

“So when it came back to doing Voodoo Ray I put all the samples in,” he continued. “Pressed on that sample and it said 'Voodoo Rage.’ and it all came back to me. So I thought, well, yeah it’s gonna be 'Voodoo Rage' now, forget about Voodoo Ray. In a way personally, for myself, it was saying I’ve progressed. I’ve got the sample now.”

I have actually not emphasized the original release of this album for a couple reasons, even though the remastered re-release in 1996 does not include ‘Voodoo Rage.’ For one, Gerald believed the track cursed the release of Black Secret Technology, since audience reach or reception greatly missed his expectations; ‘Voodoo Rage’ is a bit distracting maybe because it’s a call back to his most famous composition.

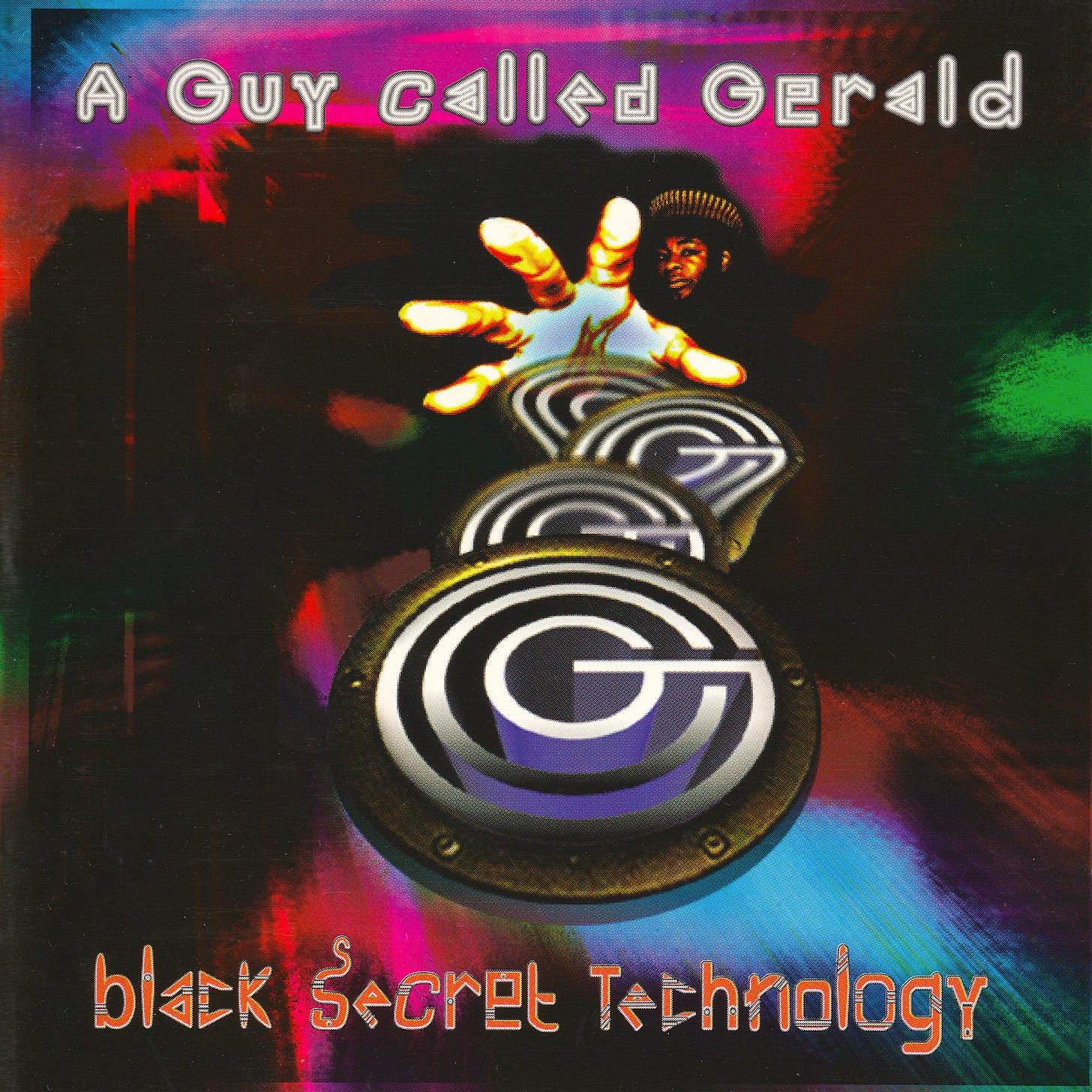

Also, the art direction of the album art is drastically different between the two. The original artwork has more of a cool, underground feel. It has a misty picture of hands silhouetted in what looks like mist or smoke around A Guy Called Gerald’s “G” logo at the time, with a silhouette of Gerald himself below playing live, all of it backlit as if one is looking at a stage in a nightclub. There is both a mystical and rave-y vibe to it.

The art direction of the 1996 re-release is quite different. It is in color, evoking to my mind the heavily tribal and African themes of the album and music. The typography does as well. At the center we see Gerald with his hand casting a spell of little “G” speaker pucks, hinting at the audiophile obsession and quality of the release.

He also added ‘Hekkle And Koch’ to the beginning on the release, punched up the bass, and included ‘Touch Me,’ which is a better fit overall for the dark drum ‘n’ bass sound of the album. While not the fan favorite, I believe the 1996 version is worthy of attention. Highlighting it here helps keep this alternate vision “out there.”

However, in 2008, he re-re-released the album, remastering it again and this time going back to the original track listing; and track titles, like with ‘Life Unfolds His Mystery’ instead of ‘Life Unfolds Mysteries.’ Ever more mysteries…