Amorphous Androgynous - ’Tales of Ephidrina’

No. 19 in our Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s

One year before Future Sound of London released their ambient masterpiece Lifeforms, they released Tales of Ephidrina to little fanfare, as the Amorphous Androgynous. Living up to this psychedelic pen name, Garry Cobain and Brian Dougans spun organic spellbinding techno laced with dark hallucinations. That tripped-out edge flew over many critics’ heads, but the seamless journey on Tales of Ephidrina was anything but throwaway. Looking back now, it stands as a key artifact in the band’s most creative phase and a work of wild, singular genius in its own right.

The year before its release, they weaved some of its DNA into their now legendary Test Transmission 2 - For The Neu Ambient Radio Station F.S.O.L. on London’s Kiss 100 FM. A radio show that mixed theater with DJ selections, some of the best techno of the era, and their own productions at Earthbeat Studios in Dollis Hill, doubling as “Electronic Brain Violence,” Test Transmission 2 was perhaps the most trippy and bravest performance endeavored by a 1990s rave act. It featured two characters, Cyberface and Yage, one helium-pitched, the other basso profondo, lurking in cybernetic channels, stitching together the storyteller — tales — with electron wizardry, metronomic symphonies, and mischievous, nervy, ambient revelries.

“The name is a challenge that we try to live up to,” Cobain explained to Mixmag’s Kodwo Eshun, a couple months before their Test Transmission 2 broadcast in late 1992, commenting on their many aliases and before they used the name Amorphous Androgynous. “But then we think of everything we do as research and development anyway. Nothing is like the final story on anything. It’s all in process and flow, rather than simply a product.” After the extraordinary success of ‘Papua New Guinea’ and fame flooding into the idea of the Future Sound of London name, they would in fact find it harder to maintain their anonymity and that process and flow. And so came a suggestion from their friend Tony Thorpe of Moody Boyz to use a different name.

They were amorphous, and in many ways, the future was androgynous. Machines defied gender because they stripped humans down to our bare essentials, the inputs typed and the outputs piped. The future was sexy of course. But the boundaries and the possibilities were both more rigid and fluid than ever before. In his memoir of the ‘90s, Ramblings of a Madman, Cobain recounted how much the cellular walls of pop culture, from commercial imagery to marketing philosophy, were breaking down in corporate wars, transformations accelerating on the street faster, than any in the establishment could fully comprehend, contrary to the anarchist fantasies of the conspiracy-pilled. In 1993, it seemed that artists were gaining the upper hand.

“Expectation is high around the table of top executives and heads of departments,” writes Cobain in the memoir’s first volume, “and we’re just about to reveal we won’t be releasing conventional singles, just further albums disguised as singles flaunting the Gallup rules for singles being able to be 40 minutes long, the first album NOT being FSOL at all but a new band called AMORPHOUS ANDROGYNOUS” — and following the lead of The Orb’s ambient epic ‘Blue Room,’ but exploding like a nova into the hyperreal through hyper speed, “so that they could use this ‘shapeless sexless’ project as a guinea pig to discard all their rules of marketing and learn afresh in preparation for the FSOL album” … Lifeforms. And so their epic future formed.*

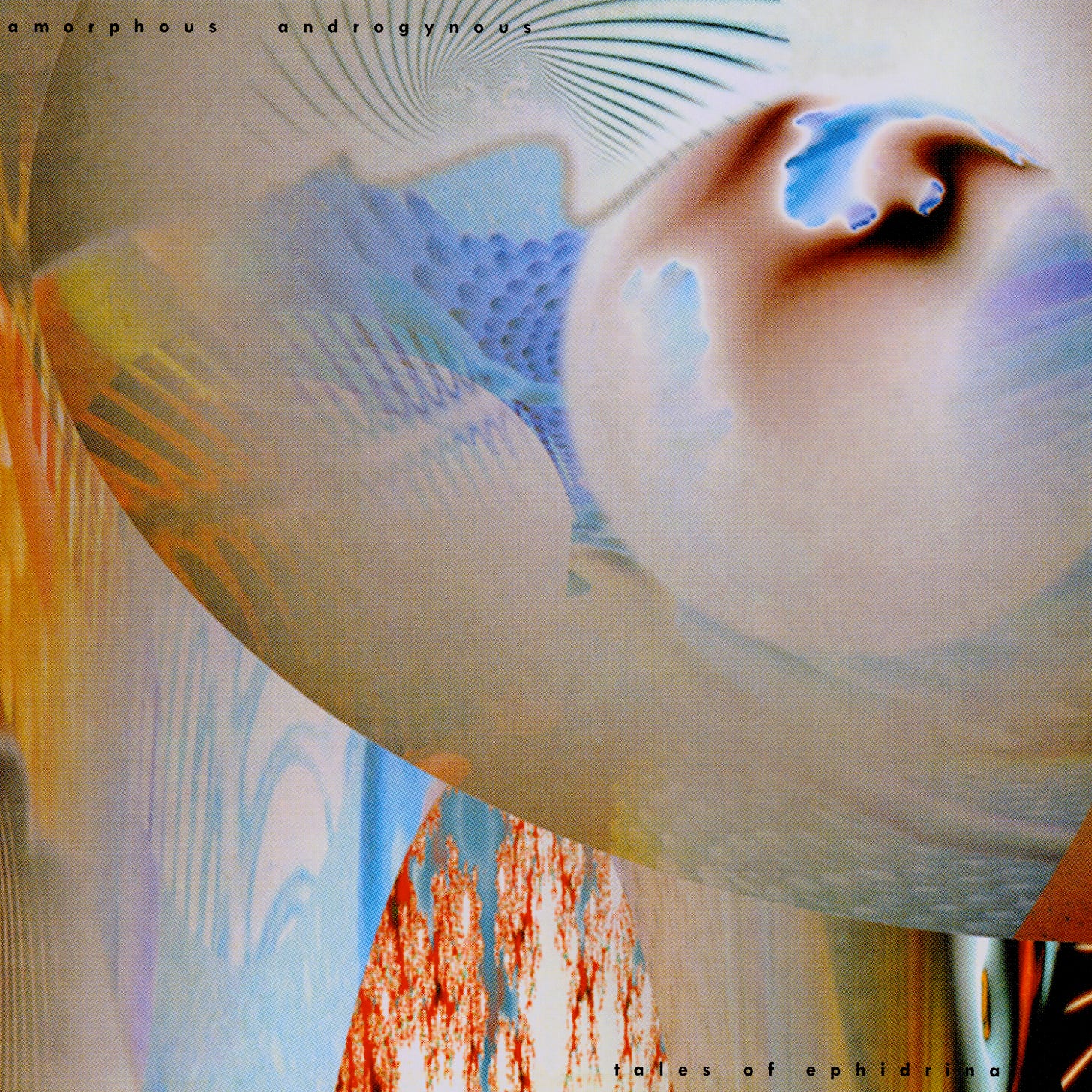

From the beginning, FSOL was on a quest. After Cobain and Dougans released their breakout hit ‘Papua New Guinea,’ they had quickly signed to Virgin Records. The duo promptly took their advance and decked out their studio with hot gadgetry, including their old Roland TB-303, an Oberheim Matrix 1000, a Bode Ring Modulator and the wily Arp Synthesizer 2600. Leaning into their gear, they went on a sampling spree, experimenting with live radio jams and video graphic transfusions. The surrealistic cover art of Tales of Ephidrina, the work of multimedia partner Mark McLean, AKA Buggy G. Riphead, is just one indicator of their feverish amoebic dreaming.**

The scene that Cobain recounts and that opens his Ramblings of a Madman, celebrates McLean. The opening chapter is titled “Bugz,” and in many ways it’s an homage to McLean but also a sendup of the music industry, the tension between art and commerce, always seemingly amorphous and ambiguous, on trial. In it, Cobain describes a bonkers creative pitch, where right after signing, McLean manically or maniacally regales Virgin executives with a reading from his psychedelic script, an audio-visual film to accompany FSOL’s new music. He paces round the table like a “lion circling bewildered beasts.” He talks of Japanese girls and dentist chairs, his fever dream going faster and faster, before ending on “wide angle — fish eye,” pausing, looking round the room, then finally, “ANAL.” Deafening silence. He overwhelmed the room with eccentrics, “looking directly into the eyes of the executives for approval of his genius.” The meeting adjourned in confusion.

Moments later, the “head honcho of Virgin,” dared by FSOL’s chess move, his reputation and serious money on the line after he had signed them, realized he nevertheless would need to take the dive with them, putting his own “madness” and marketing force behind McLean’s gonzo cry for artistic freedom — the “genius,” of these strange new electronic artists. The Virgin head honcho soon burst back in, “shouting his welcome and endorsement of us through a megaphone’….” And so, precisely because their pitch was outrageous but their timing perfect, they won: “LIFEFORMS the computer animated promo without anything like a hit single to authorize its creation from the soundscape album of the same name without an orthodox beat in sight had been signed off in addition to which,” and hence the unlikely coup in Cobain’s tale of Bugz’s hocus-pocus, the FSOL gang swindled additional cash — and the heady imprimatur for “a band no one had heard of.”

In the same cultural moment that yielded The Orb, The Aphex Twin, and KLF, electronic wizards in their own right, FSOL were changing the game on the next corporate level of musical communication without compromising their integrity. Cobain refers to FSOL as frogs, like ambient amphibians that were jumping into Amazonian ponds and river pools. “Who let the frogz out?” he concludes in his opening “Bugz” chapter in Ramblings of a Madman. Only, as his tale and as the Amorphous Androgynous would prove, leaving its indelible mark, these “frogz” exhibited a talent that was more like those of tropical frogs, like the dangerous excretions on the backs of poison dart frogs and the folk healing kambô frog.

“I’m not an expert in machinery and technology who ended up in a high-tech environment,” Cobain told journalist George Petros in 1995. “If I was an expert on computer code I’d be hacking into banks and earning a couple million.” But Future Sound of London certainly was using technology to hack musical codes and break into new zones of cultural imagining. Some of that energy was fueled by chemicals and the pair weren’t shy about their methods. And yet it was not so much recreational as it was creational, grounded in earnest research and their trans-millennial search.

The title Tales of Ephidrina made two obscure references to mind-altering plants. Ephidrina derives from the botanical genus Ephedra. Its active agent is ephedrine, which behaves similarly to amphetamines and was a popular stimulant among “studio hounds“ in the early 1990s. Scholars believe this compound was also a major possible ingredient of the Rigvedic soma — “Creator of the Gods” — related to Zoroastrian haoma, both potent potions that ancient poets and mystics supposedly drank to channel the divine. Searching the universe for answers, so flowed ancient tales from the mountains to the cities, crossing rivers, forests, and great oceans.

Clearly FSOL were reading up on these connections at the time. Their fascination shows up elsewhere. They produced another track named ‘13th Century Kitichi‘ as an ambient intro. Within the cyber-psychedelia of Test Transmission 2, they refer to their ‘Liquid Insects’ composition as “modeled on 13th Century Kitichi, which tells the tale of ephidrina.” In the book Occult Medicine and Practical Magic by writer Samuel Aun Woer, Kitichi is described as “Lord of the Earth,” one of the five elemental gods who control the mental magic granted by “Mercurian” Zodiacal plants used in gnostic mysticism. Mining these tropes, Tales seethes with a primal, animalistic force.

From the get-go it sounds like you’re waking up inside a dreamworld, a shamanic vision quest via web downlink. Dougans and Cobain also adopted a studio persona during this time that persists to this day as the name of their “engineer.” The “Yage” moniker comes from a term William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsburg popularized in the 1960s for Ayahuasca with their Yage Letters, a native Amazonian brew widely considered the most powerful psychedelic on the planet. “Yage” is also Dougans’ valence, which Cobain has long described as the more masculine side of their androgynous spiritual partnership, while “Cyberface” was their effusive side.

These atavistic associations are part of FSOL’s intellectual game. They whip it all up into an exhilarating sound clash — ‘Liquid Insects’ begins with a creepy sample from the Predator film — “Turn around! Turn around!” — and kicks to a slick, funky Herbie Hancock lick from ‘Hang Up Your Hang Ups’ from his 1975 album, Man-Child. The sly ‘Swab’ gets down to breakbeat shuffles, and punching honks and horns. The running water and guitar twangs on ‘Mountain Goat’ have made it an ambient touchstone, but its slowly lulling synth chords shine with the subliminal melancholy of Jacob’s Ladders in long sliding stairways of bliss, while ‘In Mind’ continues the ethereal drift through a cavernous dream state, rolling in a semi-conscious trance state and delirium.***

The beautiful ‘Ephidrena’ marks the album’s shift to a higher state. It weaves through columns of bass that seem to walk like giants, its banking melody flying up and down like a bird of prey — one of FSOL’s highest moments. ‘Auto Pimp’ flashes to chopper blades and a steady groove, acoustic strums intertwining with stabbing synths. ‘Fat Cat’ channels Peter Gabriel‘s Passion onto a windswept Mars, its call and response synth melody marking one of techno’s most expressive and emotional escapades. Finally, closer ‘Pod Room’ shows just how devastating the TB-303 can be in an atmospheric setting, rivaling even Plastikman‘s best seething acidic tempests.

Opening up the album’s sleeve, a neat diagram of track names, electronic studio techniques and human imprints map parallel journeys of metamorphosis: 13th century kitichi, decrescendo, slide decrease, Arizona, trapezoid, midpoint, 28 reverberations, slow blow, deep parallax, echo scale drop level, information stencil, tall buildings, oscillator filter, voice, offspring, cactus. It’s all code for their transformation into something new, something “out there” — a modus operandi that makes Tales otherworldly yet somehow unmistakably earthen — and also enlightened.

Electronic enlightenment — was that what all this “nonsense” was about? Or uncompromising “genius” creativity, depending on where you sat or hooked into it? Like that Virgin Records bigwig room where McLean helped scramble the chessboard, how the pieces are played can change the tide. In FSOL’s scrapbook history, The Most Important Moments in a Life, they are unafraid to reprint befuddled and bad reviews of Tales of Ephidrina. “Maybe Amorphous Androgynous are taking the piss,” one reviewer wrote. “Or maybe they’re just Yes with knobs on.” A sly future diss against them.

Perhaps the dig fit. Tales of a Topographic Ocean, anyone? But even if it fit on the surface, deeper down, it was something different, even alien. As Cobain told another journalist, it was all “deliberately ambiguous.” Just like “ANAL” or Cobain and Dougans traipsing around London, one in a furry vest and bare upper body, the other as dude-stoner as possible, sunglasses in daylight, coasting down the metro escalator; as the album’s press sheet declared about its artwork, they were a “soliton”: “This type of wave keeps its exact identity even after interacting with other waves.” i.e. rave…

And not rave as it would become stereotyped, everything having to go to the beat; metronomic at all times, ostracizing breakbeats to the “hardcore,” and to the tower blocks of London’s pirate radio. Raves — like the Tales diagram illustrated in its own way — were stories of strange bedfellows. Ambient was simply another space to be. “The nucleus probably never autonomous but, rather the result of intersection of ‘cellular’ thoughts from the ‘collective logic.’ It’s all about intersections from a seamless flow starting from a small pulse, an energy of a wave…” of raves…

By the time Cobain and Dougans entered their high-tech cocoon à la Terrence McKenna, these alchemical brothers were already exiting the nightclub. Their music was more fit for the dark side of the moon. Years later, Cobain would disavow drugs and pharmaceuticals altogether, swearing by Ayurvedic healing, and Medjool dates. Dougans remained an unrepentant pothead. Yet the two were still out there hacking away at the sonic jungle together. They would emerge in 2002 with their shocking Amorphous transformation into synth-rock psychedelia with new epic The Isness.

“I can describe what we do in the studio that makes rock ‘n’ roll bands look positively tame by comparison,” Cobain told Petros in that same interview. “Not a lot of people are prepared to go right into the depths of hell.” One foot still on the dance floor, the heads at Electronic Brain Violence moved and grooved on Tales of Ephidrina. And decades later, their late night phantasm still casts the perfect spell — a gutsy, transcendent and incandescent odyssey into the great dark unknown.

Track Listing:

1. Liquid Insects

2. Swab

3. Mountain Goat

4. In Mind

5. Ephidrena

6. Auto Pimp

7. Fat Cat

8. Pod Room

*As Cobain continues in Ramblings of a Madman: ”and oh yeh, you thought you’d signed dance producers bagging your slice of that hot new demographic but actually we plan a soundscape album with no beats for club promotions, accompanied by a computer graphics film with a budget equal to that of several hit single videos. Roll out Bugz with a script reading. Bugz didn’t disappoint!”

**“Walk into FSOL’s Earthbeat studio and it’s easy to see where Virgin’s investment has gone,” reported David Davies in 1993 for Mixmag magazine, describing Cobain and Dougans’ den of spiritual and psychedelic inquiry, illustrating their experiential, virtualized explorations, speculating presciently about “The Great Audio-Visual Swindle”:

“It is sleek and powerful. But somewhat strangely, the focal point of all this is a TV monitor. In front of the mixing desk and set dead center between the speakers it sits, playing, repeatedly, Koyaanisqatsi — a film without dialogue…just screens shot after beautiful shot of life. From escalator riders to sausages coming through the machine, from speeded up clouds to shamanic dancing. Head TV.”

Davies also documented FSOL’s Kiss FM radio shows evolving into a more visualized form via computer code broadcast over the Internet in the form of graphics and transmuted imagery. He even captured how they took pride in reading every communication and letter arriving at their PO Box from fans and detractors:

“EBV Organisation, PO Box 1871, London W10 5ZL” — it was as if FSOL were constructing a new shared reality with a larger community of psychic travelers. For Amorphous Androgynous was and has remained that more direct phantasm, a headspace rooted in curiosity about the inner and outer realms of experience.

***Belying their Manchester roots, the ‘Liquid Insects’ sample of Herbie Hancock takes a cue from Mancunian heroes 808 State, who sampled and sped up the whistle from Hancock’s ‘Watermelon Man,’ which in turn was inspired by and reimagined the Ba-Benzélé Pygmies’ ‘Hindewhu (Whistle Solo)’ song. In a kind of double-echo then, ‘Liquid Insects’’ sampling of ‘Hang Up Yer Hang Ups’ is a subtle homage to all.

The 808 State connection, which calls back to a wilder and more incendiary period of acid house and electronic music experimentation in the UK, is also encoded via the stabbing flute motif on ‘Liquid Insects,’ sampled from 808 State’s ‘106,’ from Quadrastate, the 1989 successor to 808 State’s New Build debut album.