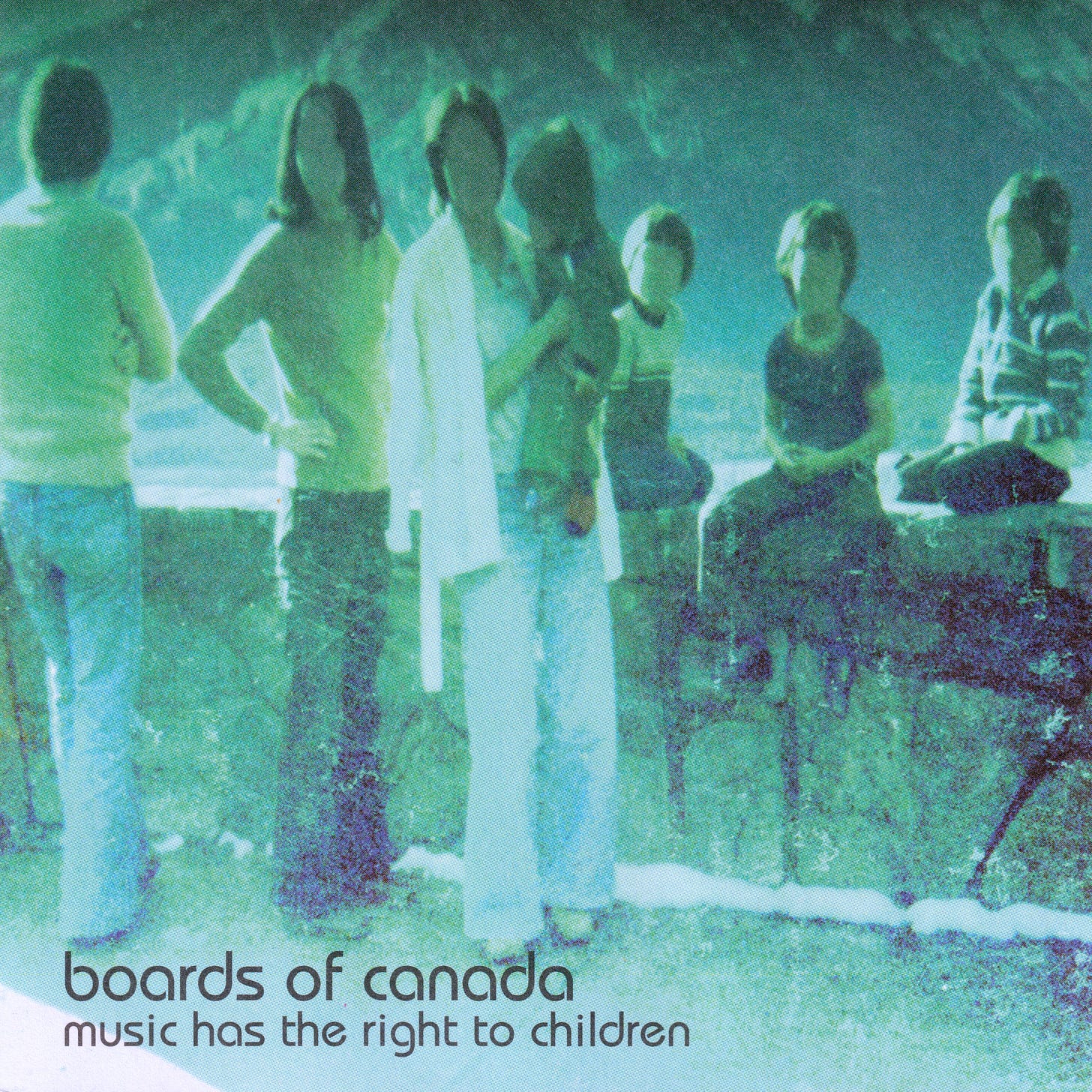

Boards of Canada - ’Music Has the Right to Children’

No. 8 in our Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s

Boards of Canada are not from Canada. They’re from Scotland. That was the first curious thing about the chill music of brothers Michael and Marcus Sandison. Far more mysterious though was their heartbreaking sound, an ingenious blend of crunchy warped beats, moody flecks of funk, and warm analog synths carving sublime snowdrifts of memory and thought, the wind blowing from a long lost horizon.

Adding to the mystique, the Sandisons were reclusive pastoralists. Unlike their electronic brethren, such as Autechre — whose label Skam Records gave them their first real break — they were not urban technologists. They lived in the Scottish countryside in the Pentland Hills, home to their Hexagon Sun studio. Heather, highlands and lochs inspired their sound as much as the snows of Canada.

Although in some ways but not all, this too was a myth. In fact, Michael and Marcus “Eoin” — his middle name that was used as his last name until 2005 to mask from the public the reality that he and Michael were brothers and both Sandisons — did not live deep in the countryside but a few miles from the outskirts of Scotland’s capital city Edinburgh, in the Pentland Hills but at the edge of its woods. And the two actually once lived in Alberta, Canada, from 1979 to 1980, when their father was doing construction in Calgary. So they were part of a tide of British families who had immigrated to Canada in the ‘60s and ‘70s, like Plastikman and Aphex Twin.*

But like Aphex Twin AKA Richard D. James, their families did not stay in Canada but moved back to Britain, their sojourn part of their sense of dislocation from and also re-affirmation of their homeland; Canada is a vast country with often white winters, cold polar winds, and great stretches of land with no traces of man, while the British Isles sit themselves with blustery cliffs, castles from myths, and yet lonely isolated towns. To be exact, Boards of Canada hailed from the eastern coast of Scotland, where in 2005, in a rare in-person interview, the two Scottish brothers took The Wire’s Rob Young on a hike off Bass Rock in North Berwick by the sea, east of the capital.

“As I crunch along the Ravensheugh Sands with Boards of Canada’s Mike Sandison and Marcus Eoin,” wrote Young, “the guano-tainted Rock takes on a mythical hue: the distance and the sea mist cause it almost to melt into thin air, the wraith of a giant white molar on the horizon. There’s a Moby-Dick quality to it — you could spend a lifetime staring at it but it would remain eternally out of reach.”**

“When I was a kid, about five or six years old,” Michael, the older of the two brothers, told Young as they walked, “a relative of mine had one of those tacky ceramic owls on their mantelpiece, and it had multifaceted diamanté eyes. I was totally obsessed with these sparkly glass eyes, for ages.” Like the giant wraith-rock, he was describing a kind of apparition. “I felt like looking into them was like looking sideways through everything, right through time. That’s what we’re trying to do with our music.”

This sense of time slipping through our fingers yet captured in striking images and memories, pervades the Boards of Canada aesthetic deep down to its core, bringing the past back into reach. “We could only exist in the short pocket of time when music has made the transition from analogue to digital,” reasoned Michael. “There’s this little moment where there’s enough nostalgia...If there’s sadness in the way we use memory, it’s because the time you’re focusing on has gone forever.”

That time marked a great human migration deeper into machines. Nature for many dwindled in the distance. The personal computer would arrive. The Berlin Wall would fall. The Cold War abated. 9/11 was on nobody’s mind. What stuck with the Sandisons was a childhood both dark and innocent. Their music evoked the wildlife documentary films of their youth, the kind once shown in classrooms or broadcast on public TV: visions of North America’s Jasper, Labrador, Yellowstone, Alaska and the Rockies; owls, foxes and grizzly bears; eagles and elk; mountains, tundras and streams.

That’s why Boards of Canada derived their name from the National Film Board of Canada, whose nature films and music scores from the 1970s were a major inspiration. But while their music channeled the outdoors, it also evoked the once mystical powers of analog technologies, from the AM radio to the cathode-ray TV set, from the copper wire telephone to turntables and tape recorders — the scratchy warping of cassettes and vinyl records, the electronic music themes of broadcast networks, and old faded family Polaroids — spawning a whole sub-genre of electronica longing for an analog childhood, from sunny Tycho to broody Com Truise. It was the flash of melodies in memories that fired up screens and projectors, before all the ones and zeroes.

“We’re recalling the echo of the melodies that marked our own childhood, and these melodies mostly come from TV, especially from films and programmes for children,” they told the French journalists Ariel Kyrou and Jean-Yves Leloup in 1998 for Virgin Megaweb magazine. “It’s the world that characterized our generation…We grew up watching the same TV programs…Like it or not, they’re the tunes that keep going around in our heads.” Tunes that opened shows that opened vistas and repeated.

Pushing against the digital tide of the 1990s, Boards of Canada crafted the ultimate monument to that analog dawn with the groundbreaking album, Music Has the Right to Children. While it paid homage to old synthesizers, it placed their imaginings within a tangible natural landscape — a vaguely northern and Arctic frontier. Their name and artwork played to this notion while the music itself sounded like bright little campfires in an audio wilderness, repeating in the circadian cadences of Sun and Moon.

Short cinematic interludes like ‘Triangles & Rhombuses,’ ‘Kaini Industries’ and ‘Bocuma’ were flashes of perfection, aurora melodies billowing on dream horizons. Child laughter buoyed chill-out anthem ‘Aquarius.’ While the ‘Telephasic Workshop’ fulminated in a cloud of lightning. ‘Pete Standing Alone’ and ‘An Eagle In Your Mind’ captured the majestic solitude of nature’s hinterlands. And the closer ‘Happy Cycling’ spun into sweet delirium like a slow tornado of birds. But it was the dreamy ‘ROYGBIV’ that crystallized their aesthetic best. It was a kaleidoscope of kid wonder, its rainbow melody rising up over a playground of broken beats and glittering keys, a nostalgic crush of whimsy and heartache that deepened and sustained its strains of fleeting innocence, raising the eyes with laughter to the skies, where all can fantasize.

It’s there that we might espy double rainbows — a dazzling phenomenon from Scotland to Hawaii — or even triple ones from time to time, the glimpse of faces or dragons in clouds that disappear with the wind, and smoke trailing up from factories and bonfires. In fact, at the heart of the album and the Boards of Canada sound was a burning fire and light that penetrated the cold Arctic drifts of time, the shining vision of a wiser mind. “One time we were out in the woods on a really wet day,” Marcus recalled to Jockey Slut magazine’s Richard Southern in 2000. “My friend bet me I couldn’t start a fire using only one match. But I managed to get this meagre little flame going in this damp little patch of ground. Then when we were about a mile down the road, we looked back and it was like, ‘whoosh!’ — the whole wood was on fire!”

“I love the countryside,” he told Southern. “I hate the idea that animals or trees or anything might get hurt. I had dreams about it for months afterwards.” This is part of the contrast and contradiction in their music that they described to Kyrou and Leloup: “We move around in the space between two extremes, light and shadow.” For it’s the perception of time in the flow of life that shines at the heart, evolutionary waves from inner space, what many postulate as that analog “warmth” — from the crackling of a fire at night to an old TV screen in the dark: Haunted but not without hope, it’s our encounter with our own nature that runs deepest throughout their finest work.

Troubled as it may be, humanity’s odd place in nature is an endless well of human creativity. Like many artists before them, Boards of Canada answered the call to be keeper’s of the flame. In Young’s story for The Wire, titled “Protect and Survive,” the brothers go into great depth about the geometric patterns and chaotic branching of the universe that runs underneath everything, and how music to them is a psychic medium, by which they can commune with people, nature, and time. Receiving nature’s energies and signs, they found a deeper path to their own inner lives.

When they were around 10, after they moved back to Scotland from Canada, often bored, the two brothers started making music with pianos and guitars. They would record a melody on a tape recorder, then get another recorder, play the first, while playing more parts while recording on the second, in effect creating layered multi-track recordings. They would roam around with friends on their beat-up bicycles making little films with their father’s Super-8 camera, freezing time. Receiving technology’s gifts and drifts, they found a new path to connecting other lives.

In high school, they formed a band, playing rock and Goth, influenced by Devo, the Cocteau Twins, Stevie Wonder, Nitzer Ebb, Wendy Carlos, and especially My Bloody Valentine. Yet quickly they drifted to synths and then samplers, discovering the unlimited potential of digital instruments, folding them into their analog bent.*** American breakbeat music also captured their imaginations — helping catalyze “hopscotch hip-hop and cranky trip-hop,” as the critic Ken Micallef described. Critically, at university, they started the Hexagon Sun art collective and began throwing parties and gatherings in the rolling hills of the Scottish countryside.

“It totally enhanced the experience,” Marcus told Young. “Once you take it to an isolated, outdoor location, away from organization, there’s a sense of freedom that kicks in. It’s sexier and less inhibited at an outdoor event — you can have 50 or 100 people hanging out around fires, some rare music echoing around…the sound of two melodies clashing over one another, or maybe a melody to your left but a voice talking to your right, off through the trees, Doppler-shifting and filtering because of the wind or the random shapes around you. It creates a giddy, surreal sound that doesn’t normally exist on records.” And so pagan nights rotated the kaleidoscope of life.

These now legendary Red Moon events cast their light and shadow over Music Has the Right to Children, and their many Music70 projects and tapes, before they signed with Skam and Warp Records. From the rumored Hooper Bay and Play By Numbers to Hi Scores, Twoism and Boc Maxima, they patiently meandered and wandered into the great weathered continent of their famous sound. The latter is in fact a more diagonal configuration of Music Has the Right to Children, released two years before it in 1996 — featuring the classics ‘Chinook,’ ‘Nlogax,’ ‘Red Moss,’ ‘Sixtyniner,’ ‘Whitewater,’ ‘Everything You Do Is A Balloon,’ and the echoing ‘One Very Important Thought.’

It’s an excellent precognition of Music Has the Right to Children, with many of the best tracks from their Hi Scores E.P. — minus the dreamy glide of ‘Seeya Later,’ and urgent dream haze ‘Hi Scores’ itself. But of the two cousins, Music Has the Right to Children benefits from a cooler restraint. Its fires are calmer and its interiority is more rugged and real. Beautiful contemplations such as ‘Olson’ and ‘Smokes Quantity’ make it a more patiently winding hike into the unknown — the perfect daydreamer music.

“There’s this track on the album called ‘Rue The Whirl,’ where you can hear birds singing,” Marcus told Kyrou and Leloup. “What happened was that I was listening to the track, and, oddly, I could hear birds singing. Then I realized that the window was open in the studio, and since the birdsong went so well with the music, we recorded it to capture the feel of what we experienced listening with the window open.” Ghosts live in RAM and Super-8 — but it’s also where and who you were with, that sticks.

“Marcus studied Artificial Intelligence,” Michael explained. “That has influenced what we’ve done. With me, it’s more numbers and their form. I’ve always been fascinated by the connection between music and numbers. Psychedelic experiences lead in this direction; they help us to see things, in terms of numbers and their forms, of structures, as if the music was made out of crystals.” So drifts the ice, snow accumulating into glaciers and melting into rivers — the wraith of the polar.

Folding the past back into the future. Entranced by the underlying order of the universe. Diagonally broken by the capricious violence of nature and the human. Boards of Canada are one of electronica’s greatest contradictions, bringing us closer to our inner truths, and each other. “We used to record compositions on cheap tapes which gave a similar rough quality, and we’ve always returned to that sound because it feels personal and nostalgic,” they told Forcefield magazine in 1998.****

As Marcus explained to Young about their persevering love of nature — its resurrections and reconstitutions are what have always re-inspired. He offered the ancient Japanese “mountain men,” the yamabushi, as exemplars, who used repeating hand symbols and drawn shapes to un-waver. “There’s a sense that you’re listening to a tune, but how many times has that been copied from tape to tape to tape,” he also reflected. “By the time it’s reached you, it’s crumbled, it’s turned into powder.”

Other than Daft Punk, there may be no other electronica group that has influenced rockers more. Like those savvy Frenchmen, the Sandisons have openly drawn on the mainstream culture of the 1970s and ’80s. It has been these recognizable sign-posts that have brought outsiders into the electronica fold — and yet there is still something incredibly quiet and eerie about Boards of Canada’s music. It has none of the cheer of alloyed pop, nor the cynicism of so many agitated, activist music-makers.*****

Is it just a beautiful soundtrack for a camping trip of the soul? Or is there a grander gesture at play? If there is a larger message behind the album, its title and its artwork suggest it’s a pluralistic one: Everyone has a stake in music. In this sense, listening to Music Has the Right to Children is like inspecting your own childhood film strip against sunlight, or resurrecting old home movies with a refurbished projector.

In each case, light is the only thing missing to transform the past into a new kind of now. When watching Boards of Canada’s private reel, that light is you. Like the hand symbols of Japanese mountain men, and the specter in the powder. Because it’s your life that makes the picture. That’s your right. That’s your music.

Track Listing:

1. Wildlife Analysis

2. An Eagle In Your Mind

3. The Color of the Fire

4. Telephasic Workshop

5. Triangles & Rhombuses

6. Sixtyten

7. Turquoise Hexagon Sun

8. Kaini Industries

9. Bocuma

10. ROYGBIV

11. Rue the Whirl

12. Aquarius

13. Olson

14. Pete Standing Alone

15. Smokes Quantity

16. Open the Light

17. One Very Important Thought

18. Happy Cycling

*In the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, in the decades after World War II, many British families immigrated or temporarily moved to Canada and other parts of the Commonwealth realm for work. In addition to the Sandisons, this included the families of Richie Hawtin (AKA Plastikman) and Richard D. James (AKA the Aphex Twin).

Importantly, Hawtin’s family ultimately stayed in Canada. His father moved his family to Windsor, Canada, for a robotics job at General Motors. James’s father moved his family to Canada before James was born for a mining job. According to interviews, James’s older brother was stillborn in Canada.

James has said that his mother, overcome with grief, used the name his parents had given to his dead brother and passed it onto him, a tale that has never been 100% confirmed. In any case, he never lived in Canada but was born in Limerick, Ireland. However, he is Welsh and grew up in Cornwall.

Interestingly, all three of them — Aphex Twin, Plastikman and Boards of Canada — ended up becoming well-known artists under the Warp Records banner, their families once international wanderers.

Also, per Marcus Eoin Sandison, the Sandison brothers obfuscated their sibling identities to avoid provoking comparisons to another famous electronica sibling duo, the Hartnolls of Orbital.

**Rob Young’s evocative scene-setting at the beginning of his Wire article invokes the Lindisfarne monk, St. Baldred of Bass from the 7th or 8th century, who resided in a tiny hermitage on Bass Rock, which sits right off the coast of Scotland. As Young describes, he “lived a hermit’s existence alone on the island, shuttered in a rain-lashed cell to confront alone his god and, doubtless, his demons too.”

***While popular impressions in the press and among fans have assumed Boards of Canada always used analog processes to create their aged and warmer sound, they in fact use a combination. Digital samplers, which use digital RAM to hold and enable the transformation of sound or music samples, are critical to their process.

“With the sampler, you have total control over your music,” they told Ariel Kyrou and Jean-Yves Leloup. “You can take the sound of an instrument, and make it sound however you like, with the ability to go back again.”

“For example, on our last album, there are some tracks where we have used a piano,” they continued. “Through sampling, we've transformed the sound of the piano in lots of different ways, to the point where it sounds like a very very old piano, or even to the point where no one listening to the album would think that there was a piano there. It's the same story with guitars.”

“We played electronic and acoustic instruments on Music Has the Right to Children, but we completely reworked their sound electronically,” they emphasized. The Akai S1000 sampler is in fact one of their favorite instruments.

****In many ways, the warping of time and space — and hence sound waves — is a central aspect, if not THE central aspect of Boards of Canada’s music and persona, though the contrasting of heartfelt melodies and paranoid moods are perhaps still deepest in their character. Whether we are talking about the fading, degrading, dropout tape effects going back to their childhoods, or their observations of mathematical and geometrical symmetries and asymmetries in nature, their universalist perception and philosophy is paramount to their artistry.

“We’re not even remotely religious people,” Michael explained to Young, “but I understand what that is about when you’re trying to channel into something that’s more about the cogs behind the workings of the universe, and it feels like sometimes everything you’re looking at is a simulation that’s based on a much more geometric background.” Heady stuff, and science backs a lot of this up. It gets headier still.

“And a lot of the time, this machine that we are seeing, the world as it is, is so smooth and predictable, that even art has become really predictable,” he continued. “It’s all following rules and patterns that have already been set by somebody who programmed it.” The “who” part is where we go beyond science a bit.

“But if you really stand back and look away from it, the potential’s there for art and music to go into absolutely bizarre territories where everything is utterly fresh and weird and new.” This is where we get into the branching of life itself.

“The challenge is to imagine: how about just stop where we are, and let’s just for a minute try and backtrack a way up here, and imagine what would have happened if, in 1982, music had taken this other branch on this side, and where would it be now, and what would it be sounding like now?”

This is a philosophy and accretion of insights and hence Boards of Canada’s intuition about music and art and its role in humanity and the universe, that appears in other interviews and stories about them. In 2001, the journalist Steve Nicholls for XLR8R described their teleology this way:

“Later on, Sandison goes on to talk about their music as a spiral or a fractal that gets more detailed the further you go in, and how they have experimented musically by using Fibonacci's Golden Ratio, a fraction close to two thirds that strangely occurs again and again in nature, and has allegedly been used in works of art by Da Vinci, Mozart and many others over the centuries, to space moments in tracks, write melodies and tune frequencies.”

Psychedelia and indeed psychedelics is also critical here. In their interviews, they have downplayed the role of psychedelics, that is in terms of being necessary to enjoy their music. However, at other times, they have also discussed altered states as a key part of their own artistic development. This seems more part of their youth or university days, when they formed the Hexagon Sun collective. Nevertheless, psychedelia as simulated or enabled through their music is a feature, not a bug.

“Psychedelics make music sound entirely different,” they told René Passet for Forcefield magazine. “Tiny details become massive, a five-minute track can feel like it's five hours long on psychedelics. You know when you're on a ride at a fairground, the pitch of the music rises and falls because of the Doppler-Effect? That's another thing we love to do in our tracks, and it's a fairly psychedelic-sounding effect too.”

Boards of Canada have applied these various facets and insights to their aesthetic and creative strategies overall. We see it very much in the artwork, song titles, and “mythology” they conjured around their second Warp album, Geogaddi, an album title itself that hinted at geometry and perhaps gadgets. Their excellent E.P., In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country, of 2000, alludes to cults as well.

"Our titles are always cryptic references which the listener might understand or might not,” they told Passet. “Some of them are personal, so the listener is unlikely to know what it refers to. Music Has the Right to Children is a statement of our intention to affect the audience using sound.”

They go onto explain some of the hidden stories and lived background to the album’s song titles, another example of them doing what many artists do, but here pregnant with more meaning in the context of how they see music and the universe:

‘The Color Of The Fire’ was a reference to a friend's psychedelic experience. ‘Kaini Industries’ is a company that was set up in Canada…to create employment for a settlement of Cree Indians. ‘Olson’ is the surname of a family we know, and ‘Smokes Quantity’ is the nickname of a friend of ours."

And even songs that perhaps have no such story, still fit within a grander theme. I would be remiss if I did not highlight the album’s great opening, ‘Wildlife Analysis,’ a perfect plaintive paean to nature’s bluesy breeze.

Of course there is also ‘One Very Important Thought,’ which closes the UK version of the album and is the penultimate denouement in the North American release — a ripple in the light and shadow of freedom.

*****I think one of the things that makes Boards of Canada so unique, and this goes to my comparison with Daft Punk, has been their commitment to their own sound and identity, both in terms of their look, branding and albums. They have been highly focused and consistent on a core set of artistic principles and themes.

This is extra apparent when one compares their more well-known work with their earlier experiments and tapes. They have described their process as schizophrenic, but there’s certainly a method to the madness. When you listen to A Few Old Tunes, Vol. 1 (1996) and Old Tunes, Vol. 2 (1996), their aesthetic DNA is as clear as day….

You have the ‘80s new wave tripping of ‘Spectrum,’ the gospel trip hop of ‘Trapped,’ the broody heartache of ‘Finity,’ the echoing expanse of ‘Forest Moon,’ the eerie Test Department-influenced ‘Mansel,’ the churchy Black Celebration techno of ‘King of Carnival,’ the sea-flute seesaw longing of ‘5.9.78,’ the lulling ‘Up the March Bank’ reminiscent of Kraftwerk’s ‘Ananas Symphonie,’ the heady ‘Nova Scotia Robots,’ native chant dubber ‘We’ve Started Up,’ hypno-techno ‘Statue of Liberty,’ Goth dancehall ‘To the Wind,’ the electro mayhem of ‘David Came to Mahana'im,’ the staccato ‘North Sea Arbeit,’ the yo-yoing ‘Fly in the Pool,’ rubbery crunches of ‘Mukinabaht,’ the happy ‘BMX Track,’ the alternate scattering ‘Hiscores,’ the gorgeously dark groove of ‘Buckie High’ — perfection — onto the bubbling ricocheting of ‘Breaking Nehushtan,’ a piano joy in ‘Orange Hexagon Sun,’ scintillatingly melodic ‘Lick’ — and the reflective ‘Powerline Misfortune.’

Yet their schizophrenic core — the space between light and shadow — photosynthesizes their spirit even further back in time. Take their very first underground release, Catalog3, with its BOC song title ‘Powerline.’ Or take their second “album,” Acid Memories, its sounds ghostly and organic, with song titles ‘Growing Hand’ and ‘Echo the Sun’ echoing from 1989. There is the mathematical titles of songs from Closes, Vol. 1 — ‘5D,’ ‘Numerator,’ and ‘Trillions.’ And so along with YouTuber Tennis Thom’s theory that ‘Focus on the Spiral’ refers to a Fibonacci sequence turning in on itself or out of itself; and onto 2004’s unofficial Random 35 Tracks Tape, which contains echoes of Music Has the Right to Children — for when we listen to a bootleg of one of their rare live shows, oh how it burns, burns, burns.

Which brings us to the structure of this “Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s” entry, where I have deliberately played with the motif of fire as the contrasting image to the snow, ice and wide wilderness conveyed by Music Has the Right to Children.

There is the accidental ignition of that Pentland Hills wood that haunted Marcus to his core. There is also his fond memories and eloquent description of Hexagon Sun’s Red Moon parties in those same hills and other Scotland countryside environs.

One of the memorable images they conjure for Young in the Wire article is a mountain valley or depression in Scotland that is unreachable by cellphone and other manmade signals — a kind of sanctuary from the madness of the world.

“The hexagon theme represents that whole idea of being able to see reality for what it is, the raw maths or patterns that make everything,” Marcus told John Mulvey for New Musical Express in 2002, connecting more dots.

“Sometimes music or art or drugs can pull back the curtain for you and reveal the Wizard of Oz, so to speak, busy pushing the levers and pressing buttons,” he said. “That's what math is, the wizard. It sounds like nonsense but I'm sure a lot of people know what I'm talking about."

At risk of being obnoxious, their remixes are a good way to observe this trademark Boards of Canada theme of persistence amid decay. Probably their best remix, of cLOUDDEAD’s ‘Dead Dogs Two,’ represents a resolutely BOC spirit, while also harnessing or diagonally moving through the voice of another artist.

Marcus, as one recalls studied Artificial Intelligence at university — while Michael studied Music — articulates the search for and expression of the deeper patterns of the universe through music in kaleidoscopic and poetic ways. This is why I find his yamabushi connection deft and touching given its cultural weave:

”Also, I’ve always had an interest in the yamabushi of ancient Japan, the ‘mountain men,’” he told Young, in what is easily the best article ever written about BOC. “They used symbols as a way of having a willpower that would always outlive any challenge. They used repetitive hand symbols or drawn characters to create a neutral place they could visit mentally whenever they faced hardship. For us, Turquoise Hexagon Sun always returns us to a zone where we can throw off the baggage and begin again.”

To put a finer point on this deep deep aspect of BOC’s resonant art — which one must also note they do a very good job of simplifying and making accessible for their audience — I wanted to last bring it full circle to their later works. The Campfire Headphases album of 2005, Trans Canada Highway E.P. of 2006, and then the Tomorrow’s Harvest album of 2013, all manage to evolve yet remain THEM.

The former two releases, which some fans did not like as much, brought in the guitar in new and fascinating ways. While it gave their sound a more “folk” effect, it nonetheless retains all the trappings and indeed foundations of their art.

And the latter, in my opinion, is one of the great albums of the 2010s, coming synchronicity-wise right after the beginnings of anti-democratic backlashes and as the growing toxicity of social media was on the rise.

Per Tomorrow’s Harvest, it is in many ways a summation of all of their earlier albums, and yet they find a way to both move their sound forward, yet within the timeless echoes of their earliest work.

Daniel Bromfield’s 10-year anniversary essay on the album for Stereogum is not to be missed. It’s a great tribute to the magic, prophecy, beauty, themes, innovation and even the silence of BOC.