Larry Heard - ’Sceneries Not Songs, Volume One’

No. 45 in our Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s

Larry Heard could see what others could not. Even better, he could feel it. He grew up in a home where everyone learned to play piano. His fingers on the keys, he would try to play based on what the sounds would tell him, and how it moved through him, and into his soul, and then back out into the world — melodies and rhythms like visions.

A quiet, introspective kid, his brothers’ friends first thought he was deaf and mute, because he often observed and waited before he spoke. Humble yet sharp, slight yet determined, studying law and architecture, the music bug bit him hard in his teens as he played in rock, funk and jazz bands, picking up the guitar, then the bass, and then the drums. And then as ever, he was happy to let the music do all the serious talking.

One of the key pioneers of the Chicago House scene in the 1980s, Heard was already a legend when he set out to give house music far more room to breathe. And yet he had always guided it from a slight remove. A live musician by training, a “player,” he was an improvisor, and a “mad scientist” in the studio, as he would later describe himself, an explorer and a romantic at heart. He set up his drum kit in the style of Rush’s Neil Peart, learning to play the “most difficult stuff” in his words, the progressive rock of Rush, Yes and Genesis, à la Bill Bruford and Phil Collins.

“George Duke, Rodney Franklin, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Chick Corea's Return To Forever. A lot of local people like Judy Roberts and Nightwind,” he told The Wire’s Louise Gray in 1992. “I was always heavily into Genesis — yes, really — and Rush, and good keyboard players. I liked Rick Wakeman. And then Yello, Kraftwerk.” And then, a journalistic slam dunk by Gray: “Right now,” she quoted him — before channelling Heard’s aplomb, reporting, “and here he holds the telephone set out to his living room” — “I’m listening to the Yellowjackets. You familiar with ‘em? Jazz-fusion.”

“Hold on,” many might say. Or even “hang up!” The Yellowjackets were not the stereotypical influence for a house music artist. They were synonymous with “smooth jazz,” and sometimes the butt-end of jokes by some critics, for their high polish. And yet, like Heard, they have maintained respect for decades as highly talented artists. The comparison in fact fits nicely, for both Heard and the Yellowjackets have had esteemed and very long careers, built on determination and devotion to the craft. Progressive rockers like Genesis, Rush and keyboardist Wakeman were verboten; however, retrospectively, they too have been recognized as masters of the craft.

Growing up with gospel, jazz, Motown, soul, rock and funk, deep in his bones, he avoided “genres” and looked at music as music, open to country and classical too. The first record he ever bought was Sly and the Family Stone but he traded in records and albums as if they were a universal language. Stevie Wonder was foundational. As was the jazz of Corea, Herbie Hancock and Pat Metheny. Across the street from his old elementary school, the strains of Earth, Wind & Fire floated all about: Rehearsing, practicing, and calling him to a life in music — their music was literally in the air.

“My parents had a piano in the house and they actively played, my grandmother, my aunts and uncles, they all played piano,” Heard told NPR’s Andy Beta in 2016. “I came up thinking that every adult could play. Music was a centralized thing that the family hovered around. My whole tie to music springs out of ‘family.’” Growing up in the 1960s, the young Heard was also entranced with the interstitial music played in between Saturday B-movies on TV as well as the records his parents played.

“There’s a weird magical thing attached to Sha Na Na for me,” he remembered, explaining that everything from doo-wop to bebop was in the mix. “It crossed all boundaries….But the thing that really got my attention was when my father brought home that first Funkadelic album. That was a big surprise for me and my brothers. We started to hear the bass lines rumbling through the wood of the house.” He learned his love of groove and rhythm, for on top of it hovered his varied and open-minded tastes and influences, his curiosity and his ferocity of vision. “I tended to be out of sync with what was popular with kids my own age,” he recalled to Ben Beaumont-Thomas in 2017 for The Guardian. “I’d record this music on to tape and join everyone at the record store with their tapes saying, ‘What is this?’” Music had zero boundaries.

Which set him on a lifetime of musical adventurism, always searching, searching, searching. Growing up on Chicago’s Southside, his family, migrants from the South, had little money. As he explained to Gilles Peterson in 2018 in a special BBC Radio 6 guest appearance, Heard was always climbing and running around his neighborhood at an early age. Parliament-Funkadelic, Mothership Connection, Average White Band, George Benson, West Montgomery, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Harry Bellafonte, Smokey Robinson, The Temptations, and Donna Summers were the soundtrack. However, he never stopped searching outside his own world. In his teens, he adventured even further, going to Kansas and Rush concerts. Peterson was discernibly puzzled — Heard explained that he was an exception to the rule.

For that rule — that Black kids like him weren’t supposed to like White rock, or progressive rock bands like Yes and Rush — was foreign to Heard. He didn’t like staying in boxes or limits on who he was or what he liked. “I just wanted something different,” he told Peterson. “Like direct consumer on the radio, I could hear all those all the time. I love Aretha Franklin and Al Green and all that stuff. It was on the radio. But I wanted to get to some things that were kind of more expanding my mind first, stuff I hadn’t heard.” One can hear that influence throughout his career, the steady churning of ideas, the tension between simplicity and complexity, and even self-indulgence to a degree, but like Rush’s ‘Fly By Night,’ riding on flights of melody.

“The thing about being a musician, I discovered I was a musician,” he told Lauren Martin in 2018 at the AVA Festival in Belfast. “I didn't become one. I discovered I was just pretty much bred to be one, in the environment that I was in. Both parents playing piano. Sight-reading. Hearing them play notes correctly, play chords correctly.” Music was not an alien thing but nature itself for Heard. “That stuff is going to be ingrained into your psyche right from the cradle,” he continued. “It is kind of like riding a bike. Because you get a new kind of bike, you don’t think about riding the bike any differently — you just get on it — and you start pedaling — and having fun.”

It was that natural musicianship and having fun that led Heard on his many experimental journeys and discoveries in sound. By the time he was a teen, he was playing in bands, most notably the jazz fusion and progressive rock band Infinity (with fellow future house legend Adonis). And while his musical second nature was lifelong, his mastery still took time and effort, especially given his varied interests, his jumping from instrument to instrument. “No one just jumps in with a paintbrush and becomes Rembrandt, just because you feel like it,” he told The Guardian’s Beaumont-Thomas, describing how his skill was decades in the making. “You have to pay your dues. It’s like flight hours with pilots: I got a tonne of flight hours playing instruments.”

But all that skill somehow led him to the back of the stage. He learned to play extraordinarily difficult drum parts, like Peart’s work on Rush’s epic 2112, but that fascination with rhythm earned him a diminished creative voice. “I left the last band because I wasn’t really getting any creative input. I was just playing the beat. I guess it was traditional for the other members of the band to not be very receptive to the drummer having ideas because everybody just assumed that the only thing the drummer was capable of doing was playing the beat,” he explained to Resident Advisor’s Mohson Stars in 2008. And so the history of deep house began….

“I wanted more involvement,” he told Stars, “so I finally decided to leave and buy myself a keyboard and try to develop some of the ideas that were in my mind.” Those ideas were revolutionary. The day he brought a Roland Jupiter 6 synthesizer and a Roland TR-707 drum machine home, he made the classics ‘Mystery of Love’ and ‘Washing Machine’ that same day. It was like lightning — “I had all of these ideas bottled up inside of me.” The former was the first strike of an electrical charge romancing the future, strutting at a languid 110 BPM, its synth-pads seeping throughout, its robot-swing swirling in a slow, sweet delirium. The latter also reverberated around the world, a fast take that tripped dancers the fuck out.

Of that seminal, loose, drum-snapping and gloopy track, that converged with Phuture’s own groundbreaking ‘Acid Tracks,’ but without the benefit of the squelchy Roland TB-303: “‘Washing Machine’ was just a recording of me fooling around with a synthesizer and changing the different modes,” he told Gray. “It wasn’t intentionally an acid track.” And yet it is one of the greatest acid house tracks of all time. It ricochets, a rhythmic drum assault with reverb suggesting “physical space around the sounds,” as much as it’s synth sorcery — with gaps of silence and hi-hat cymbal attacks. “I always wanna hear something different from the things you hear on the radio all the time,” he told David Toop in his 1995 book Ocean of Sound, “just wanna hear someone venture out, take a chance when they’re making music. It sounded weird to me. In the end my little brothers liked it. They thought it was kinda cool.” It was like a washing machine.

The b-side was just as extraordinary, the third thunder-strike in a storm of creativity. Written on a snowy night in his Chicago loft, ‘Can You Feel It’ was the pioneer song of a new era that signaled the soul all wished to imbue inside a world of machines. The UK label Desire released a mash-up version with a voice repeatedly shouting, “Can you feel it!?” sampled from a Jackson’s 1981 live performance and Chuck Roberts’ spoken-word near-sermon about the mythical origins and power of house music, sampled from Rhythm Controll’s 1987 track ‘My House,’ in 1988. Inspired by the classic Jamie Principle songs ‘Waiting On My Angel’ and ‘Your Love’ — the two attended the same high school — Heard’s more communal take opened vistas.

Works of genius, Heard’s trio of anthems found their way onto reel to reel tapes, Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy turning them into instant underground staples of the Chicago gay and arts club scene. Almost overnight, Heard transformed the trajectory of electronic music. Here was the midnight fever of a musical genius finally let loose. “All I would see is the crowd of people outside at midnight,” Heard said of the venue that gave house music its name, The Warehouse, which he had passed by on nights walking home from his day job, before his music was released. “Cabrini-Green, the housing projects from the opening of Good Times, that’s the area,” he told NPR in 2016. “Back in those days, that was skid row: lots of homeless, prostitution and pimping going on. It wasn’t the friendliest area.” House: new life in dark places.

Ironically, Heard was mostly unaware of the Chicago house scene. He made his groundbreaking compositions in isolation of its social and musical gatherings. But his friend Tony Harris soon took him to a party. “As I came in, Robert Owens was playing the vinyl of ‘Mystery of Love,’ so I thanked him and we started chatting from there,” Heard explained to Beta. Right off, Owens and Heard decided to collaborate, and produced ‘A Path,’ with Owens on vocals — “One day you'll wake up…You go out searching…fiction to reality, a path we all must take” — it was a revelation in the history of house music. Part of the gay music scene, right as the AIDS epidemic devastated Chicago’s underground community, Heard’s music became a salve.

Which is maybe why he titled his first album Another Side as the leader of house group Fingers Inc. Recording early on as Mr. Fingers, his new effort, Fingers Inc., was comprised of Owens and Ron Wilson on singing duty, and Heard as producer. Owens was an aspiring singer who had an earnest and preacher-style delivery, but of a lover to another lover. He had a “shopping bag of napkins and pieces of paper,” things he wrote while on breaks at his jobs. “Having no reference for songwriting, you just ad-lib,” Heard told Matt McDermott on Resident Advisor’s podcast in May, 2016. “I had plenty of experience doing that in my jazz-fusion bands, so improvisation wasn’t a scary thing to me. Even now, every time I go into the studio, I have no clue what’s going to happen.” And that complete openness to creative chance yielded magic.

Another Side is perhaps the greatest house album of all time. Released in 1988, it stands as a landmark, only available in the UK for decades on Jack Trax; but with new reissues starting in 2014 in Japan, it has found a new audience in the 21st century. Its 16 songs all punch above their weight, starting with the electro-bounce of ‘Decision,’ Owens and Wilson, whose father was a doo-wop baritone in The Flamingos, dishing heavy emotions and straight-talk — “Somebody’s heart is gotta break. Somebody’s heart is gonna break” … “Is it going to be you? You? You!? Yoouuuu!?” — soul and improvisational music at its best. It’s what people used to meaningfully call “hot.”

From jazz to funk to house — deep music — Heard’s command of the free spirit of invention coupled with old tradition married the trio to a unique moment in time, never to be repeated again for its innocence and invisibleness. ‘Shadows’ for example is an absolute stunner of a song, rocking like a boat, flowing like a river, a timeless beauty and one of Heard’s greatest instrumentals. The title song ‘Another Side’ begins with nature sounds, of water and birds, sways and shuffles, Owens and Wilson singing, calling and hollering in low and high harmony — “Where am I? We’re strangers in another place and time … You see, I feel this warmth from their troubled mind,” Heard’s keys answering with a trance-like equipoise, “I’d like to let them know someone cares on another side” — with a synth line that stretches to sunrise.

The psychedelic ‘I’m Strong’ and the grooving ‘A Love Of My Own’ lead into the dreamy ‘Distant Planet’ — “Wanna release all my motion / I’m ’a set my mind free / Take me to my vision / So far away from me” — the album concluding with a trio of moody calls to living fully, the sultry ‘Feelin’ Sleazy,’ the Kraftwerkian stomp of ‘Music Take Me Up’ and the organ-to-synth majesty of ‘Mystery Friend’ — “There’s a moment in our lives, when we all must feel the drive / There’s a moment in our time, when we all must turn and strive / Mysteries of love, oh... love... love... love… love!” While the classic ‘A Path’ single started the Fingers Inc. journey — “One day you'll wake up … You're trying to find a dream / Deep inside, emotion” — Another Side delivered on house music’s improbable post-disco feeling of resurrection within a profound contemplation of alienation and redemption. Sitting outside the 1990s, before, similarly to Kraftwerk’s masterful Tour De France Soundtracks in 2003, sitting opposite ends beside the decade, Another Side ever looms as a guiding star.*

And yet as Heard explained to Resident Advisor’s Stars, that vision was greatly obscured by isolation and even discrimination. “We’ve sold records here, but house music has always been seen as a taboo here,” he explained of Chicago. “Even disco was taboo; it was perceived as very gay, very drugs, very Black, and house music was seen the same way. So you have to be a gay, Black drug addict to go dancing. Who made that rule?” In 1988, the American radio waves were dominated by U2, INXS, Guns N’ Roses, Madonna and Rick Astley’s ‘Never Gonna Give You Up.’ Heard’s Another Side was simply too radical then for the mainstream, as was its origins.

Yet Heard was hot — hot enough for Big Life to put out his next album in 1990, a collaboration with Jungle Wonz’s Harry Dennis, The It’s On Top Of The World; and for MCA Records to sign Heard as Mr. Fingers for his first solo album, Introduction, after Jack Trax put out the compilation album Ammnesia in 1989 without Heard’s consent. The ‘90s would be a winding path for Heard filled with promise and false dawns, his uncompromising vision and love of music too much for the majors and even for the independents. “I’ve never followed any directions,” he reflected to Mixmag’s Mandi James in 1992. “I have enough frustrations coping with my own creativity and the logistics of marketing and record companies,” adding “I have to remain true to my music, my own direction and let it flow.” And so he did, after escaping the storms.

While his name carried great respect in England, including rumors of a production collaboration with Sade, any chart success he had in America was often treated as a fluke. MCA would release Heard from his contract for his Mr. Fingers followup, Back To Love, put out on Black Market International in 1994. And like Introduction, it pushed Heard’s piano-driven house sound in a heavy rhythm and blues direction. Heard himself took on singing duties, showcasing his soft and sweet tenor. Songs like jaunting ‘Closer,’ ethereal ‘Survivor,’ the gospel-crying ‘Mystical People,’ and a gorgeous tropical house instrumental in ‘Sweet Wine,’ broadened his rapport. Nevertheless, his efforts failed to maintain altitude in Billboard’s top charts.**

Working different jobs, to maintain his artistic independence — from the Social Security Administration to a doughnut shop to a television station to motherboard manufacturing — and making music, with faith in the creative unknown, Heard was seeking balance and freedom. But the waves between big label promise and his truth were immense. Chicago and what it represented, from Knuckles and Hardy to Jesse Saunders’ ‘On and On’ and Marshall Jefferson’s ‘Move Your Body’ to Steve “Silk” Hurley’s ‘Jack Your Body’ and Heard’s own ‘Can You Feel It,’ was like a maze. He couldn’t extract himself from varying expectations and the city’s desperations.

And so by 1994, he went to a new place. He went deeper. On March 3rd, 1994, recording in his new studio, over the course of ten days, he wrote 9 songs without stopping. He did little sound design, just played on his instruments, using the presets, including with his favorite, the digital synthesizer and a staple of the 1980s synth and pop sound, the Yamaha DX7. Except here attuned to the rhythms and space of house music — a new landscape for the imagination unburdened by the heavier commercial interests of most radio and MTV. The result is Sceneries Not Songs, Volume One.

Different from Another Side or most anything he did before, Sceneries Not Songs, Volume One was purely instrumental and improvisational. It was almost like a return to the first days, of ‘Mystery of Love’ and ‘Washing Machine.’ Just plug it in and go. No hiding. No delaying. No pulling back. Each “scenery” is like a wave. It just goes, and whether it is gentle and slow or more urgent, there is an incredible sense of a new freedom from “form.” Not formless. But forming anew for the very first time. The beginning scenery, ‘Dolphin Dream’ feels like the muse forming inside of music.

It begins with a simple keyboard motif and then a drum machine kicks into place. Matching the music, it indeed sounds like a dolphin’s dream — watery, shimmery, dreamy. There are cross currents and streams of melody bubbling, deep murmurs underneath and shining ripples of light overhead. The pulse is soft, aquatic, the hi-hats splashing gently, a groove through the waves. And then a little over two and half minutes in, a brooding synth that rises and twists and dives and delights in the deep, deep mystery of time. Eight and a half minutes long on an album with no vocals, the ‘Dolphin Dream’ meandering was a stark departure from Heard’s passages thus far. Twinkling, sparkling, sparse then ornate, hypnotic and conscious, it is a revelation.

Of course, it is tempting to write it off quickly for its quirky and unfussy synthesizer preset ornamentalism. But its soulful essentialism, its unpretentiousness and its utter lack of self-consciousness, is what makes it an eternal wind on the waves of musical change. ‘Tahiti Dusk,’ the second track on the album, lays back while it skips forward on jazzy breaks, keeping a by-the-shore atmosphere of cocktail drinks and a cooling breeze on the cheeks. The strange muttering of sea animals drifts through, giving it just the right touch of the weird and wonderful. We are clearly no longer in Chicago.

They were sceneries, he said, not songs. But what does that mean? “It’s something I had more flexibility as far as creativity. Since it’s not a song, I don’t have to go by the song rulebook…following any set patterns or the status quo,” he told Chal Ravens in 2018. “I can make songs but maybe not every time you want to do that. You want something more freeform.” He was on the other side of his first phase. Let it flow.

“There’s no structure to it,” he elaborated to Gerd Janson in 2005. “‘It doesn’t seem like this guy does anything intentionally. He just gets on the equipment and he starts doing something,’” he said, impersonating a puzzled listener. “And that’s exactly what I do. I hate to have to think too much because then it turns into work, and I want the music to be a pleasurable experience and I think even on a primal level that’s conveyed to people. You have a component of our being called intuition.”***

And intuition is at the heart of the album’s greatest moments. The chug-chug locomotion and melodic mellifluousness of ‘Midnight Movement’ is one of Heard’s greatest accomplishments. Over ten minutes long, it’s a perfect train of thought, an electric piano pressing into the heartland of a new dream world, at ease in its search and yet restless in its spiritual mission, keys crashing out of one another — the tip of a wave like no other save for maybe Underworld’s epic surf, ‘Thing in a Book.’ But here, it is thing in the moonlight, at once calm and wide awake, riding the jazz in the machine. ‘Snowcaps’ follows at the perfect moment, a more reflective almost barren ambient lookout on Kilimanjaro or Denali or Mount Fuji, clouds slowly drifting by the peaks.

Melting those caps, ‘Summertime’ is just what its name describes, a sunny joyous experience. Fun, spry, carefree, strutting and smiling, three minutes in, its melodies shift, the light dancing through the leaves and the trees, a Moog synth-line scrawling through a cityscape enjoying days upon days of bliss. It’s sweet and warm like love’s embrace. Ninja-like drum breaks snap, click and kick off an irresistible groove. More than a decade after the original release, the Japanese label Spiral Records reissued the album and its sequel Volume Two in 2007, as part of their limited Electric Soul Classics series. Listening to ‘Summertime,’ you can hear how this lively yet gentle excursion into soulful ambience would speak so deeply to Tokyo, and its artistic community, a futuristic city absolutely obsessed with jazz and its floating world.

“Sceneries Not Songs, Volume One, were powerful works in the sense that they expanded the genre of deep house, and these were also very significant works for him in the sense that they marked the beginning of his later developments,” the Japanese journalist Itaru Mita wrote in the liner notes to the Spiral Records reissue. “Depending on the album, it is possible to listen to them as cosmic works today. Larry Heard seemed to be stumbling around in the rough seas of rave culture, but he finally established his own direction when the scene started to settle into its own.”

It was that Yellowjackets thing. Fusion. A refusal to follow anyone else’s trend. Freeform. A willingness to get lost in order to find the next form. Intuition. The only way to stay true to oneself in a new frontier: ‘Winter Winds & Chill’ is that brief little doubt, or respite, a chill — the shiver one feels when the cold night air greets you, entering and admiring the wide open clear. And it doesn’t have to be the snowy mountains. It could be the desert or even the tropical ocean after the Sun long disappears. ‘Caribbean Coast’ is a cool running reggae vibe tune — a rhythmic Rastafarian deep house heaven — watching the waves under the full moon.

It’s a third act that evokes the dance floor more than the previous two — but nonetheless never abandons the natural sceneries of Heard’s musical imagination. ‘One Three Five Seven’ alludes to the time signatures and concentric melodic chords that he unfolds at will as he enters the album’s final stretch. It rolls and rolls into itself, a restrained yet expressive house beauty, like the spray and ripples on the crests of barreling ocean waves. ‘Question of Time’ closes it out with a late night jazzy and overflowing grace note. It’s as much what it says as what it doesn’t. There is a satisfying sense that we have arrived at a whiskey bar high up in Tokyo’s vast skyscraper-scape, just as much as it’s an answer to the modern techno city’s relentlessness. Its keys burble and chase the Sun into a quiet ocean sunset.

Unsure whether MCA would legally block him if he used the Mr. Fingers name, Sceneries Not Songs, Volume One was the first time that Heard recorded under his own name. When asked about the songs’ scenic titles, he explained to Ravens that he hadn’t necessarily been to any of the places they allude to, only that he dreamed of them. “I’ve never been to the Caribbean coast, but that’s what I imagine this kind of open, airy, kind of floaty thing to go along with the clouds and the horizon and the water,” he told her. And so the music told him its name, when “I’m trying to do something really crazy” — a vision of places where Heard could also escape.

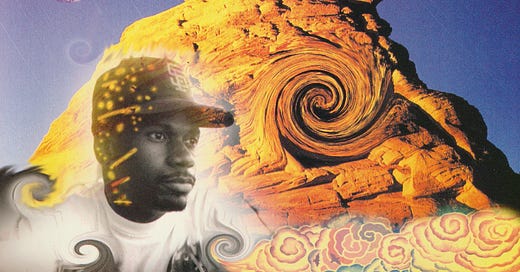

Like the album’s cover art, which was crafted by Toshio Nakanishi — aided by computer graphics tech Issei Furukawa — of Japanese outfit Major Force, Heard was coming out of some psychic storm and climbing and running into a vast new frontier of his own making. He had created a new musical language for human exploration. Stars spinning overhead, burning bushes ablaze, planets resting on his shoulders, waves and vortices of creation swirling all around his inner calm — Sceneries Not Songs signaled many more adventures to come. In 1995, his Volume Two would arrive unexpected and once again he ventured out into new seas, lands, possibilities.

There was something inside him that words could not express — going back to childhood, as he explained, he was the odd one out. “I do things by feel,” he would say. “A lot of times,” he told Stars, “if I try to describe my music to people, I don't really get through to them. If they hear it, nine times out of ten they like it.” So those kids who thought he was a “deaf-mute” were maybe hearing him on some deeper level, by perceiving his silence as listening to something farther away. He was different. Because he could hear what others could not. His family had taught him that impossible thing. Vision. And it gave him the courage to keep seeking peace.

For there was perhaps a chaos that he had never talked about at great length. Intensely private about his life, he has talked about his challenges in family and love in more general terms, however. Growing up on the Southside of Chicago, while it was a childhood filled with music, it is not hard to imagine there were darker echoes in his universe that were hard and painful and that extended well into his adult life. When talking about his family, Heard has mentioned that he took on the heaviest burden following his parents’ divorce at 15, working at McDonald’s to support his mother.

“It’s no secret that I’ve been through a lot of hard times,” he later offered the New Musical Express’ Andy Crysell in 1996. “Based on my life, all the music I make should be pretty sad.” And yet it wasn’t. Running underneath all of his escapist fantasies is a deep resilience. As he explained to Ravens, after exiting MCA and then creating his Alleviated label and releasing his more personal visions, you “either face it and conquer it, or give up.” At long last, with his wordless Sceneries Not Songs — envisioning a new musical freedom — he was free to be Heard.

Track Listing:

1. Dolphin Dream

2. Tahiti Dusk

3. Midnight Movement

4. Snowcaps

5. Summertime

6. Winter Winds & Chill

7. Caribbean Coast

8. One Three Five Seven

9. Question of Time

*The vinyl version of the album, more tailored toward DJ’s, included four bonus tracks. ‘Can You Feel It’ and ‘Mysteries of Love’ (‘Mystery of Love’), obviously caught DJs and new fans up with his two first anthems. A new version of ‘A Path’ with slightly different lyrics also was included in the vinyl version. And ‘Bring Down The Walls,’ Fingers Inc.’s fourth single, bouncing to the same metallic synth bass that Heard deployed on his first hits, rounds out the release.

I would also note here that while Daft Punk’s 2001 masterpiece — Discovery — could arguably be the post-’90s bookend opposite Another Side, rather than Kraftwerk’s Tour De France Soundtracks, I chose the latter because it is quintessential versus simply brilliant, popular, and critically acclaimed. To my mind, Kraftwerk is a more perfect comparison to Another Side. It is stark and energetic in a similar fashion. Fittingly, both are still growing in recognition.

**In the ten year period from 1985 to 1995, Larry Heard was simply overflowing with music, much of it still never officially released. René Gelston, his longtime friend, advisor and “manager,” played some it on Peterson’s radio show, much of it on cassettes. Brilliant tracks, like the arpeggiating cascade of ‘Stars,’ and the effervescent, beautiful ‘Gaullimaufry Gallery,’ with Owens on vocals, stun.

“Sketches, sketches, sketches, sketches,” he told Chal Ravens, “hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands…harvest things.” It was near impossible for anyone to keep up with Heard in those days. His Gherkin Jerks alias is another example, with its clickety-clack rhythms and gorgeous synth spiritualism on ‘Red Planet’ and the chirpy, acidy, whacky classic ‘Reznaytor’ — one of a kind.

***Improvisation is at the heart of everything Larry Heard does musically — as he’s explained. His versatility as well as his meandering musical trajectory, is the result of a searching mind. From Blakk Society’s gorgeous ‘Just Another Lonely Day’ to The It’s joyous ‘Gaullimaufry Gallery’ to the beguiling ‘Genesis’ to Loosefingers’ ‘Glancing at the Moon’ and ‘Lamentation,’ his music will ever seek to change live in the moment.

This means his music can be sometimes hard to follow because he switches aliases and sometimes his overall artistic direction from album to album, and for years moved from label to label. And even within a musical piece, he is often in no hurry to hit his listeners over the head with hooks or nostalgic samples. It is very minimal music compared to many of his peers in that he adorns his music very little with tricks.

“They’ll say it’s the typical working stiff that buys the albums,” he told Mohson Stars of record clerks who would give him feedback and insight. Heard has a little sense of humor about it. “Not real young kids, high school age, it’s the older people. Aging club-goers, I guess.” Of course, the young kids continue to discover him.