Rolling over the horizon and skyline was a vortex of energy. It tore rifts in the spacetime continuum, it seemed like, crossing the oceans and channels between continents and islands and countries and peoples. It opened a portal into a new world: Neotropic — “new lands.” From Asia and Europe and America, and Australia and Africa and Antartica, birds and ships and ideas and dreams migrated far and wide; and from villages to the mega cities, a woman echoed the future back to the beginning.

She was the voice of the Future Sound of London: “You are listening to a test transmission for the new ambient radio station, F.S.O.L.” She was one with the ghost inside the city’s man-machine: Riz Maslen — journey-woman, musician, magnifier. In 1996, she was the toast of the London trip-hop movement, the biggest artist on Ninja Tune’s Ntone ambient label. But long before the mid-’90s, she was helping map out the next hundred years and beyond — shadowing and inspiring behind the scenes.

It was in London’s Dollis Hill neighborhood that her tutelage, under none other than the Future Sound of London (uploading her into their “Earthbeat Central Computer”), revealed the mysterious ways of the sampler. In 1992, the beguiling duo FSOL took to the airwaves with their Test Transmissions 1 and 2. Across the city, listeners heard her silken voice introduce their far out visions of cyber-living, a radio theater for robots — one of the strangest yet most innovative sonic documents of the 20th century. Taking some of the most exhilarating techno of their rave ascendance — from Kenny Larkin’s ‘Northern Lights’ as Pod to the Richie Hawtin favorite, Reload’s ‘Amenity’ — and then combined with a clutch of their own tunes and experiments, the pranksters at Dollis Hill enlisted Maslen as a stealth partner in a wild new psychedelic consciousness.

“I moved to London at the beginning of the whole rave explosion,” she told Ghost Deep in 2018. “I had grown up in a small community and all of a sudden I’m immersed in this huge metropolis and it’s all kicking off. I ended up working with a guy who was doing a lot of hip hop and dub reggae and that’s when I met Brian and Garry.” It was the late 1980s and the transition from a rock-centered youth culture was quickly chain-reacting with the new wave convergence of American house and techno, Teutonic kosmische Musik, and the post-punk stylings of Manchester, greatly accelerated by the likes of New Order, the Stone Roses and soon, FSOL.

Hailing from the West Country of England, Maslen had started out playing in a band with her sister, using drums, guitar and what she described as “ramshackle” sounds like scraps of metal and tape machines. Working with a guitarist, she was exposed to more indie styles like The Cure and The Cocteau Twins in the ‘80s, applying four-track tape loops of vocals she recorded and backing guitar distortions. So when Maslen met Brian Dougans and Garry ‘Gaz’ Cobain of FSOL, they shared similar groundings and sonic philosophies. They were outsiders ever curious about the next, next frontier.

“They were in the same studio complex,” she explained, noting that it was Dougans’ 1988 breakthrough as Humanoid, with his TB-303 ‘Stakker Humanoid’ release, that sparked their connection. “I had obviously heard ‘Stakker Humanoid,’ and someone said, ‘Well yeah, he’s the guy who wrote [Stakker Humanoid].’ So I went up and said, ‘Oh you’re that guy who did that track with the 303.’ At that time I hadn’t experienced making music with something that electronic, like using a computer, and those were the days of when you had an Atari ST. So they introduced me to the whole thing of using an Akai sampler. That was my first real stepping into the electronic world.”

Getting her own “central computer” and plugging it into a keyboard and sampler to source and infinitely transform any sound she found or curated, Maslen began her musical odyssey, working with Dougans and Cobain early on as a ready audience, confidante and collaborator. “That was a really interesting time to be in London,” Maslen recalled. A singer and keyboardist at first, she was turned on by the DJ propulsion of sounds in London, perceiving the open door to expand her own experiments and horizons outside the stereotypical molds cast for a woman.

Exploring this new electronic world, she tapped into the primal and futuristic.

When listening to her debut album, 15 Levels of Magnification, it’s easy to imagine Maslen exploring and navigating the new frontier of ‘90s rave London, with its blazing nightclubs, side street underbellies and working class laundromats. It’s the sound of a generational yet individualistic awareness: the sense that the more the world became interconnected, the more it also became voyeuristic. What she chose to access was not just city or country but something her FSOL cohorts also longed for: a humanity accelerating into a deeper kind of consciousness, a neo-tropic expanse of artistic resiliency and idiosyncrasy, expressed in keen studio grooves and dance moves.

“I remember the first time walking into their studio,” she described of that deeper immersion into the core of what was to come. “This is when I had really been poking a hole around at what they had at Dollis Hill. I was just amazed at all this equipment that was in there: banks of synthesizers and outboard effects, a couple samplers, and a mix-board desk. And they started playing stuff and I was just like, ‘Wow!’ I was just completely blown away.” At first, she did some singing sessions for FSOL; then, assisted by Dougans, she set up her own studio kit; watching FSOL work, she emulated their approach, learned from trial and error, and innovated fast.

It’s that acquisitive and streetwise side of Maslen that drives 15 Levels of Magnification forward. From voyeurism to auteurism, she had the courage to leap forward and believe in herself, in a studio culture that mostly shunned women. It wasn’t a thing at Dollis Hill. She was part of a family. But she still had to strike a forward path in her own way. While her early work shares a lot of FSOL DNA, nevertheless it’s suffused with her own unique story and identity — openers ‘Northwest 37th’ and ‘Laundry Pt.3’ locate her on a journey moving onward.

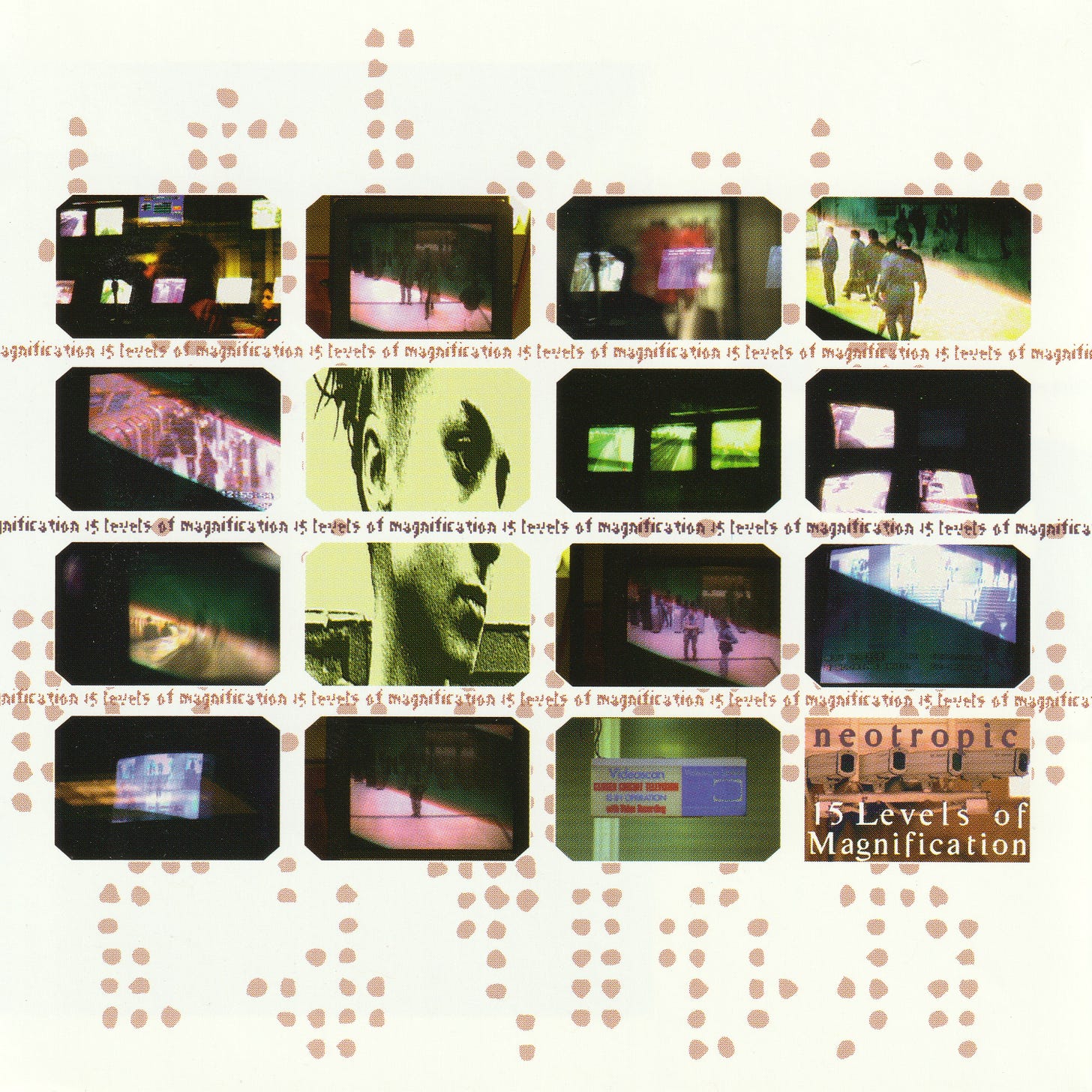

“Around that time, I was living in Gloucester Place, just round the corner from Baker Street, and began to notice the high number of CCTV cameras,” she told the journalist Matt Anniss for Juno Daily, wondering back then if she could be tracked on a walking trip across central London. “At the time there was a certain amount of paranoia about the increased use of surveillance cameras, and it was starting to feel like nothing was sacred any more. The album was almost about the oppressiveness of surveillance in cities, and how you could escape it if you looked hard enough or knew where to go.”

The first quarter of the album is a swirl of urban states, from birds crowing to washers cycling, an almost Sherlock Holmes magnifying glass of life in London, with its mixture of parks, shops, pubs and clubs. Two Neotropic trademarks come through loud and clear besides the sampledelia: grainy jazz-funk themes and crunching breakbeats. ‘Northwest 37th’ wakes to standup bass and Amen cymbal crashes, spiked with a trippy synth weave answered by a flute motif and then another whistle motif — all under gentle waves of gossamer synths — piercing and yet restrained. It’s the cleverest of gambits, slipping by camera-eyes and gliding with a bird’s eye.

But is it daylight or midnight? ‘Laundry Pt.3’ tumbles us underground into the London drum ‘n’ bass sound — a cool yet heavy number, it’s neither ambient, nor jungle, but a compelling Maslen hybrid that wigs out with head-banging attitude inside smoke rings rising up, up to the stars. On ‘La Centinela,’ gears shift just right as its snares snapping and whipping, stir the mind; Maslen’s vocals wisp and shimmer from below onto high; its strings and sax engross us in the mysteries of the sublime. An absolute classic, it demonstrates everything she learned at Dollis Hill while also throwing down the distinctive voice and skill of an artist in command of feints and patient thrills.*

But just as much as Maslen deftly channeled her inner soul, whether through her singing or her synth notes, she excelled at merging moods with machines. The almost morose fidgets and squeaking brakes of ‘Laundry (Pt. 1),’ with its coin slots and slosh of spinning, takes the cliché of industrial sampling and transcends it with longing and a sense of transient communion. Perhaps this reflected her sojourn to New York City right before her Ntone phase where she encapsulated her global passions, her Small Fish With Spine project on Andy Shih’s Oxygen Music Works with 1995’s Stickleback E.P. evoking impressions of travels: Goa, India’s ‘Siolim’ and ‘Anjuna Fleamarket,’ of California’s funky ‘Hollywood,’ and Japan with ‘Meiko,’ her Atlantic to Pacific drift.

Shih’s OMW was a critical transition point for Maslen, the Small Fish With Spine project providing an alternate route into DJ crates, her ‘I Hate You’ song getting an epic “Trancehall Jam” remix treatment by San Francisco’s Freaky Chakra. In the very male world of record stores and backroom smoke-outs, she slid and swam. Small Fish With Spine’s ‘He Builds the World’ would earn prime status as the key uptick track on Rockers Hi-Fi’s essential DJ Kicks: The Black Album entry — the toast-rapping of Patrick “Farda P.” Plummer floating his righteous style over Maslen’s deep trip.

For Maslen knew the hidden maps and routes of the emerging global polyrhythm, returning to London to retrace her own heritage back to the future. The album’s title song, the drum ‘n’ bass classic ‘15 Levels of Magnification,’ which would get a deluxe remix package with contributions by her old Dollis Hill friend Noel Ram AKA Leon Mar — the Reinforced Records stalwart, Arcon 2 — flurries and flips, rolls and thunders, uppercuts and knocks out, its dread-bass and boxing breaks winding and snake- charming. The fact that Ram changed it just so with his remix, speaks volumes.

In the early ‘90s, she had moved through the city with ease. At the Dollis Hill complex, near the exit of the Dollis Hill tube station, artists like Suede and The Police’s Stewart Copeland would come through to rehearse. She played keyboards for The Beloved. “I was very lucky to be there at that time,” she told me. “Obviously, Reinforced moved in and you had Reinforced Records, which was great. So it became this really interesting mix of music at Dollis Hill. Goldie used to turn up and hang out with Dego and Marc. We had a little pool room where we would all hang out and play rounds of pool.”

In the Dollis Hill attic, Reinforced — 4 Hero (Marc Mac and Dego McFarlane) — were busy helping invent hardcore and then drum ‘n’ bass, the breakbeat theme running relentless from 4 Hero and FSOL to Neotropic, Moody Boyz and Leon Mar. It’s this London breakbeat fascination that would carry much of the ‘90s rave wave before Daft Punk would gradually reassert the metronome. Maslen was at the frontline as Reinforced released 4 Hero’s Rough Territory and Parallel Universe, and Arcon 2’s Liquid Earth and The Beckoning. Coming from an adjacent frame, FSOL propelled head-trip hardcore with Smart System’s The Tingler E.P., and later of course, the dreamy breakbeat classic ‘Papua New Guinea,’ with debut album Accelerator.

But that was just the beginning. As much as the aftershocks and ripples of rave fractured into dizzying sub-forms, the space and time away from the dance floor was filled more and more with a new consciousness. What in some ways started out as a revolution soon gave way to reflection. Deep house. Ambient dub. “Intelligent Dance Music.” Trip hop. At one angle, so-called “electronica” was becoming something like the dissolution and dilution of rave and the bold future it once promised. But while some shook their heads, others nodded. The dilation of rave was not simply an opportunity for artists to explore but the advance of rhythm to the outer core.

Maslen’s 15 Levels of Magnification is a study in time and rhythm, and how it can absorb, flow, break, stop, and stir. All that hardcore rhythm would be meaningless without the calm of after and before. The second act of her Magnification wanders into something like the everyday — ‘Weeds’ seems to loiter in a daze, its stoned jazz filling the spotlight with dust motes and beams of shadow. The slow motion is its own kind of respite from the rhythm of the machine, the clanging of a clocktower waking us to the sun’s many long cycles of time; ‘Nana’ seems to creak like a rocking chair, horns rejoicing in the lowering light of the day, the chirps of birds going back and forth above some courtyard or alleyway; ‘Nincompoop’ continues with her jazzy odyssey across London but with little laser drums, creating a hint of swing that runs from techno-house to hip hop, breaks, and drum ‘n’ bass — and to their many hybrid children.

“‘Neo’ — I like — and it means new. I like the word ‘neo.’ But also I kind of wanted to create something, a word, a place, a tropic, so ‘new lands,’” she explained. “I kind of used to make up words as well. You write things down. Someone would be sitting by you, talking, and I loved traveling on public transport — you start hearing things — I would be on a bus, I used to have a little book — you could hear conversations and write it down. But I think neotropic came out of something I was watching on TV.”**

Worlds overlapping and transporting and transmitting, words and notes and little overheard conversations, whether from people or machines or the Earth — recorded and sampled sounds of a city and a land and a universe — levels of magnification. She was listening and observing and transforming: ‘Electric Bud’ fuses all of these visions and collisions into an electro chameleon reminiscent of Jedi Knights and Two Lone Swordsmen but 100% Riz Maslen, with slight hints of FSOL’s tribal excursions and Reinforced Records’ sci-fi beat mysticisms. Nocturnal, ‘Electric Bud’ rattles with chains and fences, rumbling with brooding bass — another Londoner classic.

Which brings us to something like Neotropic’s inner perspective: ‘CCTV’ echoes unending in a kind of dub magnification chamber, its flute and harmonica trailing up onto the ledges and edges of façades and ceilings and eaves, where closed-circuit cameras capture and then slither their sleuthing back to a room with many screens. Yet out there, that spider-like voyeurism cannot reach every inner sanctum or private moment of peace: ‘Neotropic,’ a sort of understated peak of the album, is a statement of greater intent, the gentlest tap and motor of forward motion, like a flat boat on the slow river by the shore, the serene enchanting chanting of an Indian singer in a melismatic Gamakas mode, reminding us that life is but the deepest dream.

Whether on the Thames or the Indus or Goa’s Mandovi River, as she has teased throughout the early movements of 15 Levels of Magnification, here Maslen finally begins to fold bolder elements of her Indian and British heritage together into her Neotropic central computer. Like waves lapping and then breaking onto our ears, ‘Neotropic’ stands up there with some of the best work of ‘90s ambient masters Irresistible Force, Global Communication and FSOL, its long synth pads easing, mesmerizing and healing, rivaling Amorphous Androgynous’ ‘Mountain Goat.’

For the inside was the outside, and back and forth it goes, emanating, dilating, reflecting, magnifying. Like the aperture of a camera and its convex lens, now the story of Maslen’s first masterpiece comes into focus: who is this refracted woman coaxing and trailing the land’s hidden ghosts? Like many of the electronica artists of her generation, from Aphex Twin to FSOL, she was not a London native. She lived in different parts of the city. In Dollis Hill, it was working class in the ‘90s — with a White, West Indian and Vietnamese descent and immigrant population — “a real mixed bag of cultures” as she remembers fondly. The Dollis Hill studio complex itself where she got her start was unfussy, “a bit of a rundown place,” owned by a decent “right geezer.”

Her childhood in the Cotswolds was different. It was bucolic and its population was mostly White and homogenous. Maslen was also different. Her mother’s family was from India. Her great grandfather had worked on the Burmese railroad during World War II. Her younger sister looked White, but she and her brother looked more mixed, with dusky complexions making them stand out, inviting sometimes unwanted looks, questions, and mistreatments. And yet the isolation also provoked her imagination. Growing up in a small village by a forest, she enjoyed the mystical heritage of the English countryside with its little streams, rolling hills and ancient trees. It was a deeper connection to the primordial and a wider world, one before the machine.

“There’s also that witchcraft thing, which weirdly enough happens to be a fairly common element culturally in rural parts of the UK,” she explained. “There were a lot of druids in the place where I grew up. So there really is this weird dark element that was always very much there. And so I was fascinated with the underworld in the city too. I thought it kind of filtered through in my work. I do love that — because I never want it to be too pretty. I wanted layers. You strip away a layer and — ‘Ooo! There’s something else there!’ — but not always so packed that you can't get through it.”

As if wandering through forests, we come to a mysterious ‘Beautiful Pool,’ which begins with a sample of Catherine Bott singing on Trevor Jones’ ‘Gelfing Song’ from the 1982 fantasy film, The Dark Crystal, a favorite from Maslen’s youth. So it’s in many ways a London gothic moment of reflection, a mythic time jump of the druidic past into the machine future, the Jim Henson cult film and its phantasmagoric puppet creations themselves a kind of multi-temporal, multifaceted hybrid. It’s a sort of companion to FSOL’s ‘My Kingdom,’ from their Dead Cities album of the same year, which also samples another 1982 film classic, Ridley Scott’s sci-fi film noir, Blade Runner.

Looking back on her love of found sounds and capturing memories of popular connection, she revealed a big genesis moment in her creative realization: “When I was really small, I was really into taping stuff off the TV,” she said. “I had a little tape machine … I used to love watching sci-fi films, just taping bits of dialogue … Yeah, it’s just weird, as a kid — I still have a tape of it somewhere, a cassette of it — I remember — I had a dog at the time named Merlin. He’d come in. You can hear him snuffling and I’m chatting to him. I must have been 11 or something. Just sweet. Quite bizarre. And years later — there I am — sitting and using a DAT machine to record sounds off the street. It’s just crazy. And I would then feed that back into the sampler.”

Like the cover art of 15 Levels of Magnification, designed by Ninja Tune’s Kevin “Strictly Kev” Foakes, we can see and hear Maslen coming into integrated focus with her sweet story of Merlin: how memory is alive and sampling is a magic portal of time. Coming from the other end of the spectrum — with Mary Hopkins singing on Vangelis’ ‘Rachel’s Song’ — ‘My Kingdom’ and ‘Beautiful Pool’ are both swan songs in a way, of the golden age of sampling, with copyright exclusions increasingly restrictive in subsequent years. And yet both prefigured the 21st century obsession with the voyeuristic realms of the multi-sensory “metaverse,” and the no-holds barred explosions of user-generated content and piracy that powers so much of the commercial Internet. Sampling then as artistry. Surveillance now as theft.

Flowing perfectly into ‘Regents Park,’ the breathy vocals and wheezing beats of ‘Beautiful Pool’ — twanging to Eastern strings — whisper then of a deeper tranquility far beyond the screws and turns of corporate control and the abuses of one authority. Regents Park is in Inner London north of the Thames. It is filled with fountains and a lovely boating pond with waterfowl and herons. It includes the London Zoo and the London Central Mosque, and just outside its Outer Circle, is the Sherlock Holmes Museum. As a song, it projects the inner peace that all city souls need to seek.

So we come to the album’s last levels of magnification. ‘It’s Your Turn to Wash Up’ meows with the funky wah-wah riffs so prevalent in late ‘90s house and chill-out music, but quintessentially Riz Maslen, expertly distorted with an acidy TB-303 creeping in, its wiggles simultaneously spry and lazing, a contrapuntal worm of spirited resistance to the grind and the glum. Here it feels as if we have indeed returned home, closing the door behind us, washing up, readying for the next circadian trip under sun and moon, a fading gesture of the traveller’s groove.

‘Aloo Gobi’ retreats further into the introspective mood that Maslen sets for her masterful conclusion. She brings us round a table inside a world growing ever more global yet local. A curry dish traditionally made of cauliflower and potatoes, Aloo Gobi is a staple across India. Far away in London, it has also become common — part of the identity of not only England but representing something core to Maslen. It chirrups. It cascades. Its beats and bass sustain. Its sparse piano glistens. ‘Aloo Gobi’ is another ambient chill-out standard, building just the right anticipation at journey’s end.***

Which comes in the form of ‘Frozen Hands,’ a sensation every English person knows from cold and wet winters. Whether in London or the Cotswolds, we are now looking out of a frosted window, Maslen’s almost operatic trill hanging like mist over its icy drums, mournful yet uplifting murmurs in the deep, tablas giving us warmth. Its anthemic techno synths evoke Orbital and A Guy Called Gerald. This is Maslen. Hopeful and enduring. Universal and personal. The sound of London eternal.

And yet — as a druid of techno, she also conjured lands. For we are ever and anon back inside the dream. No matter how many tall towers or scrapers of heaven, we can see the sun warming the window glass. And like the seagulls in ‘Papua New Guinea,’ her voice shape-shifts into what could be — birds flocking to the skies and to the trees, echoing memories from afar — as it should be.

Track Listing:

1. Northwest 37th

2. Laundry Pt. 3

3. La Centinela

4. Laundry Pt. 1

5. 15 Levels of Magnification

6. Weeds

7. Nana

8. Nincompoop

9. Electric Bud

10. CCTV

11. Neotropic

12. Beautiful Pool

13. Regents Park

14. It’s Your turn to Wash Up

15. Aloo Gobi

16. Frozen Hands

*I wanted to note here that the later overseas releases and streaming versions of the album greatly abridge ‘La Centinela’ from over five minutes to about 50 seconds. The original UK album release contains the full song. In order to hear and get the original versions, I recommend going to Neotropic’s Bandcamp here. You can also get rarer material on her Bandcamp, like her releases for OMW and R&S / Apollo.

**I have here decided to italicize parts of Maslen’s quote to emphasize the emotion she put behind both her love of words — the naming of “Neotropic” — but also how she cherishes the process of sampling, journaling and re-imagining the worlds in which she moves and lives in. She’s a very open interviewee, and so I wanted to capture the almost musical way she talks about her past, present and future.

***As important as it is to highlight Maslen’s female identity, given the general lack of women producers in the ‘90s rave and electronica wave — putting aside the genre’s heavy use of female singers — it is just as important to note her multiracial heritage. These musicological aspects of who she is make her remarkable music more so.

That is, her music speaks for itself, outside her identity. But also it is enriched when understanding her artistry and her art, from inside her identity. The Indian aspect of her sound is not just a Neotropic trait, either (e.g. recording as Phreaky for the 1996 Planet Dog compilation Feed Your Head - Accelerating the Alpha Rhythms, she expertly weaves classical Indian accents into her nimble ‘Blob’ dub gem).