“Even a stopped clock gives the right time twice a day…

Even a stopped clock gives the right time twice a day…”

By 1993, acid house was taking the world by storm. At the head of that charge were two brothers who had a gift for marrying incendiary rhythms with euphoric melodies. They called themselves Orbital — a name inspired by the M25 “orbital” motorway that fed Greater London’s outdoor rave scene. Their first two hits — ‘Chime’ and ‘Belfast’ — were wordless wonders, perfectly capturing the communal energy of electronic dance parties across Europe, while the wicked Butthole Surfers-sampling ‘Satan’ hinted at their quixotic sense of adventure, never ever losing their nerdy sense of humor.

But rock fans and critics were still scratching their heads with this new sound: the common deceit was that techno had no message and no soul. Phil and Paul Hartnoll were the antithesis of that stereotype. They had grown up steeped in punk, hip hop and working class values. Both were concerned about social inequality, politics, the planet, and the dangers of technology. (They were members of Greenpeace and in 1996 recorded ‘The Girl with the Sun in Her Head’ using a solar generator.)

“Orbital live in a more ruthless world,” they told The Wire’s Louise Gray, when compared with the little fluffy clouds dreamworld of The Orb, drawing a circle of distinction in attitude as well as name. “Our music is about loops and time and space,” they offered further, highlighting the more stark, abstract, and universal nature of their electric sound. “Maths and topology” is how Gray described it. Or as the New Musical Express captured the band’s image — “Orbital have still principally been portrayed as ‘sound engineers,’ egghead science lab students with oscilloscopic thought patterns. But look at their past and they’ve got more in common with Chumbawamba than Kraftwerk.” They were hackers then who would shape the sound of the world.

“Even a stopped clock tells the right time twice a day,” repeats ad infinitum on Orbital’s second rave trip, as they toured by bus across the U.S. in 1992, taken from the British cult film Withnail And I. “It popped up in America a lot,” Paul told Exposed magazine’s Phil Smith, also explaining that the album’s cover had an octopus brain on it. “There was this collection of videos and they were all complete crap — apart from about three. So we ended up driving these vast distances across America watching Withnail And I again and again. That line pops up and seemed so appropriate.” Orbiting their world, electrons streaked and flashed with a fateful synchrony.

Techno was predominately instrumental music. It still needed words and word of mouth to help convey its message of self-empowerment: that the poetic meaning of its interacting notes and beats was democratic and infinite. So Orbital’s exhilarating second album, 1993’s “Brown Album,” made that case better than any other. It was packed with sheer sonic joy and a raw primal energy. Yet it was its clever odd voice samples about time loops and stopped clocks that firmly placed the listener in a pinpoint relationship with history and the cosmos. Even though they themselves resisted putting too much meaning to their sounds, a heady concept emerged.

The starter ‘Planet of the Shapes’ was a sonic war of the worlds. Its blow-torched sheets of sonic metal crashed and hovered over Jupiter beats, opening to a serene melody piped from within, as if played by the mythic god Pan himself, enmeshed in elastic elysian drones. ‘Lush 3-1’ and ‘Lush 3-2’ wove through melancholy notes with chugging rhythms in an Edenic spring rain. ‘Impact (The Earth is Burning)’ tipped a hat to dinosaur-killing asteroids, muscular bass plunging into a maelstrom of baroque chaos, while ‘Remind’ set things adrift with the Earth’s surface still smoldering, a descending frequency blasting the sky and cutting loose to banging drums.

This epic dive into techno’s belly and its heart would mesmerize audiences “in the know” years before Daft Punk would convert the masses. In Los Angeles, on the heels of Orbital’s third album, Snivilisation, the brothers Hartnoll would return in triumph to the City of Angels, sending imaginations scattering across the night-scape. 1994’s Millennium Trilogy event, by event producer Philip Blaine, would hold its second performance at the Shrine Exhibition Auditorium. The previous year, things had misfired with Circa ‘93, when Orbital, Aphex Twin and Moby encountered the revolutionary power of America’s rave scene in the form of a mini LA riot.

“We were literally lying on the floor because we didn’t want to get a brick in the head,” Paul Hartnoll told Spin’s Jeff Gage in 2021. “It just looked like a scene from some ’80s cult movie.” This was the wave that Orbital was riding across the globe. No one had seen or heard anything like it. Sound waves that felt as tall as buildings, as fast as shooting stars, as deep as oceans, as interstellar as the human imagination. High emotions, low frequency oscillations, psychedelic locomotions, Orbital 2 remains essential document No. 1 when it comes to tripping back into the fantastic.

“Enormously entertaining and relevant at the same time, the British brothers observe the state of the world and the personal and public conflicts between civilization and nature — industrialization vs. humanity — while keeping the audience jumping,” the journalist Kinsey Rowe observed for Variety, right in the mix at Millennium. Also in downtown LA’s rave epicenter was Perry Farrell of Jane’s Addiction and Porno for Pyros fame, loving and rocking to Orbital’s heady refrains. Performing from an elevated tower stage at the center of the Shrine, the Hartnolls ruled the future.

“That was mad, we met Perry Farrell at that same show,” Paul recalled to Ghost Deep 20 years later. “I was so naïve. We were interviewed by Traci Lords, the porn star, and she introduced us to this guy. She said, ‘This is my friend Perry!’ He just had this look about him, like a pirate with striped trousers. And I thought, ‘That must be a pimp! He looks like Huggy Bear.’ That's what I assumed. Such an unusual character. He was very friendly. I had thought he was just a dodgy LA type. That was a great show.” Emanating from London to LA, Orbital 2’s repercussion was immense, from the pastoral flutes of ‘Planet of the Shapes’ through the hellfire of ‘Impact’ and its astonishing ending. Distant worlds collided. Diverse people united. Time became a loop.*

‘Walk Now…’ continued Orbital 2‘s progression, its didgeridoo suggesting an aboriginal Dreamtime, the hunt for prey afoot. ‘Monday’ made a break to industrial clocks, its contemplative melody conjuring the prospect of endless Mondays spent in cubicles — sci-fi jazz with a stiff drink. But the album’s truly most astonishing moment came last with ‘Halcyon + On + On.’ It was dedicated by Paul and Phil to their mother, a tribute to her battle with addiction to the prescribed Halcion insomnia drug. It’s one of the most beautiful compositions in the techno canon — its warm waves and uplifting groove moving through sadness and pain to joy and optimism.**

“It was like ‘What does this track remind us of?’ … I found it quite mellow but I found it to be a first-thing-in-the-morning track,” Paul told George Petros for Seconds in 1994, thinking back on his memories of those Halcion days. “It reminded me of getting up in the morning with my parents having the radio on and the sort of atmosphere that was created by the radio playing and nobody talking while drinking their tea and eating their toast. I found it conjured up that atmosphere for me. The morning time of a housewife in suburbia. You thought of the Halcion aspect, didn’t you?”

“It was a very Valium-type atmosphere,” said Phil, connecting their music to that deeper and more troubled time, when the family’s trust in the system completely let them all down. “I listened to the tracks and it sort of tied in with that. My mother did take it for seven years and all sorts of weird shit went on from my adolescence and Paul’s puberty. We had an older brother who locked himself away upstairs and Dad was working all the time and Mom was going psychotic on this drug.”

“I’ve been reduced to tears while writing music,” Paul explained, sharing with Petros the deep emotional pull of their music and its source. “I try and stifle it if I feel like I’m gonna cry when I’m making music. I try and stifle it because if I gush forth those tears then I’ll find it hard to continue on with the track. To stifle it retains that mood a lot longer. If I find it happens, I try and compose as quick as I can.” Petros described Orbital’s emotional expressionism as intimate and biological: “each wave-form cascades into the human head through alert ears,” he concluded, “and is then funneled to the heart, becoming an analog impression of a heartbeat.”

In the context of the times, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the first Gulf War, ‘Halcyon’ evoked the dream of eternal peace. The word “halcyon” is the ancient Greek name for kingfisher birds once believed to nest on calm seas. Like the Future Sound of London‘s ‘Papua New Guinea,’ ‘Halcyon’ was part of an introspective tide in electronic dance culture, a turning away from hedonism to consider deeper questions about life and the mixed promise of new technology. It has graced funerals and wakes, and remains a touchstone for ravers who heard its call to healing and feeling.

Orbital still remains a great synthesis in that quest, having returned from two retirements, the strongest in 2017 with the spirited Monsters Exist. They were less accessible than bands such as Underworld and The Chemical Brothers. Their ’90s output was more purely electronic — and at the center of their music was a tough emotionality, drawing on the Hartnolls’ anger about the environment, politics and social injustice, with choice and biting voice samples, many doubling as enigmas, spliced from Star Trek: Next Generation, Withnail And I, and a sci-fi French film, channeled from La Planète Sauvage or Time Masters, dubbed in English.***

The way in which Orbital 2 attuned the soul to these troubles and questions gave expression to inchoate yearnings for global harmony. At the dawn of the Internet Age, long before its devolution into political violence, it was electronic music that gave that impulse its highest art form and expression. Orbital’s carefully chosen words were sly collective signposts to that outlook of extraordinary hope. Stepping through, the rest was pure, unadulterated magic. It is, quite simply, perfect.

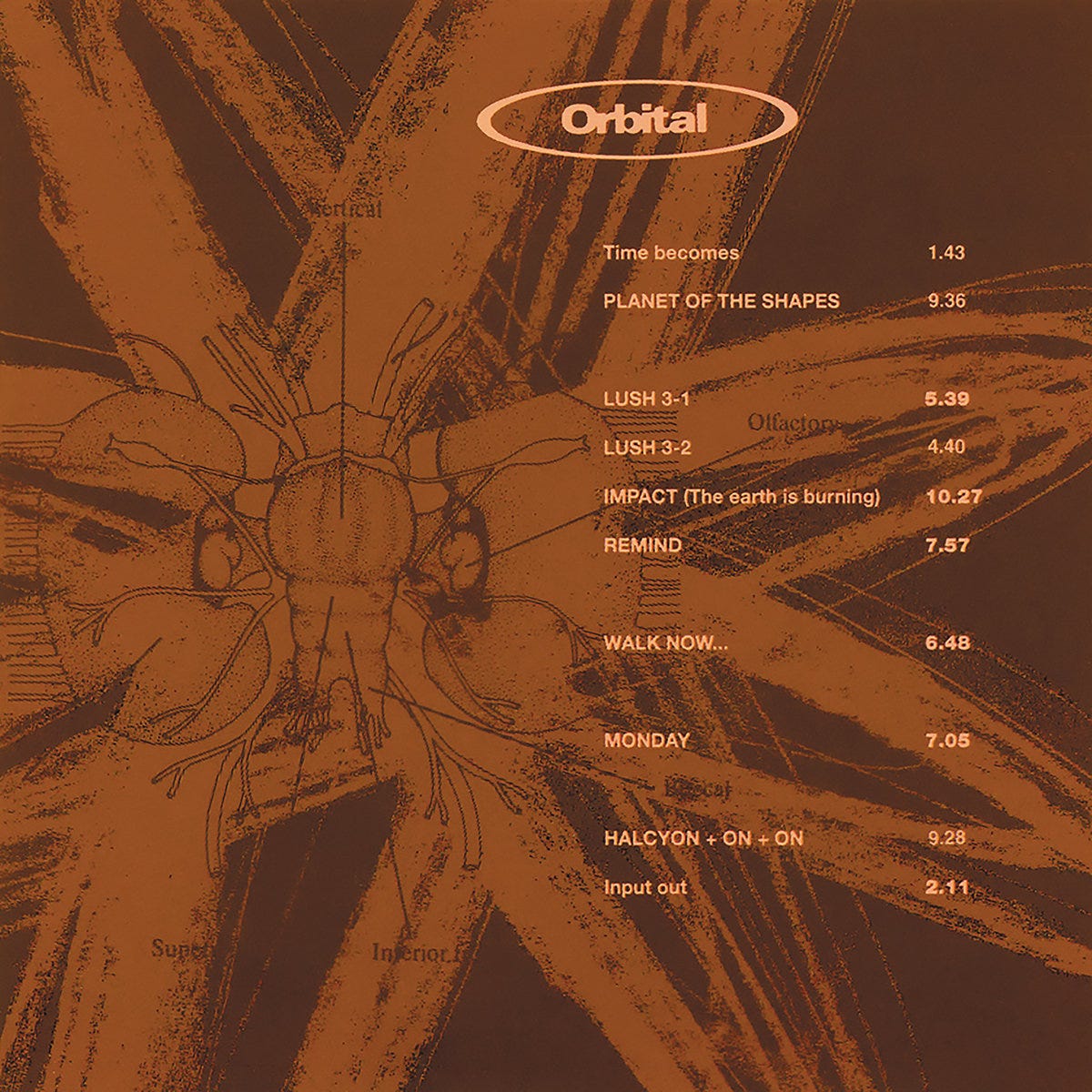

Track Listing:

1. Time Becomes

2. Planet of the Shapes

3. Lush 3-1

4. Lush 3-2

5. Impact (The earth is burning)

6. Remind

7. Walk Now…

8. Monday

9. Halcyon + On + On

10. Input Out

*909Originals talked to Orbital in 2020 to capture some of the stories behind the “Brown Album,” including little sonic jokes and puns, like the repetition of the Star Trek “time becomes a loop” voice sample of Lieutenant Worf on ‘Time Becomes,’ which was also used on the first Orbital album for its opener ‘The Moebius’ — a playful trick for their fans in a little sleight of déjà vu.

And on ‘Planet of the Shapes,’ they sampled a scratchy vinyl record looping at its beginning, another little head trip, contrasting with the clearer and cleaner sound of the digital compact disc (CD) format of the day. ‘Walk Now’ also sampled someone walking across a street Down Under:

“It is the sound of an Australian pedestrian crossing. Well a Sydney one anyway. I noticed they are a bit more mechanical sounding in Melbourne. The didgeridoo I sampled is the one I bought on the same trip.”

I think it is also worth reiterating here that Orbital and their globetrotting had a major impact on techno’s longterm trajectory. In addition to their tours, they were effective visual communicators.

For example, their t-shirts with two little Elroy Jetsons characters made them approachable, while their dark long sleeved and bright orange shirts, gave their fans a slick sci-fi fervency.

**’Halcyon + On + On,’ named after the Halcion triazolam drug, as well as a washing machine TV commercial catchphrase (“and on… and on…”), has been an Orbital live staple for decades now — Orbital even sampled Bon Jovi’s ‘Shot Through the Heart’ during its breakdown in newer renditions, going back to their late 1990s tours; but the longer running inversion of pop is their brilliant usage of Belinda Carlisle’s vocals from ‘Heaven is a Place on Earth,’ which is almost dangerously cheesy, but with its cheeky wink and Carlisle’s ethereal delivery, it soars — combined with ‘Shot Through the Heart,’ it also makes for an acid test of humor, humanity and ingenuity.

Also, it is important to note that the song’s core vocal is Kirsty Hawkshaw, sampled from her Opus III hit, ‘It’s A Fine Day,’ but utterly transformed into something much more poignant than pixie. Also, the album’s final track, ‘Input Out’ slowly slides a sample of Dudley Thompson saying ‘Input translation, outward rotation” from a documentary by the BBC about oil derrick pumps and other slider mechanisms, looped into a rotation and translation of time’s cyclical nature.

***One of those mysteries we may never know the answer to, Orbital is unsure which film it comes from. They sampled it from the TV one night, a “cry for survival!” Most likely it is from a BBC broadcast of Time Masters in 1991, an English dubbed and renamed version of the 1982 sci-fi animated film, Les Maîtres du Temps. It was directed by René Laloux and designed by the legendary Jean Giraud Mœbius.

Last but not least, ‘Remind,’ perhaps the most incendiary and rousing song on the album and in the Orbital catalog, is an instrumental version of Orbital's remix of ‘Mindstream (Mind The Bend The Mind)’ by Meat Beat Manifesto.