Orbital - ’Snivilisation’

No. 36 in our Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s

“The sound of the future folding in on itself.” — MOJO, 1995*

In 1994, Roger Morton, writing for the New Musical Express, revealed that Orbital‘s Paul Hartnoll had a recurring nightmare from childhood about the end of the world, that he relayed while contemplating the guts of a Russian nuclear submarine.

“I’d be looking down the hill towards the sea and you’d see the mushroom cloud go up,” Paul told Morton. “You’d feel your bowel loosen and this warm feeling of horror. I could see my dad doubling up in pain. And then I’d turn round and try and go into the caravan, and someone would say, ‘You can’t go in there,’ and I’d say, ‘Why not?’ and they’d say, ‘Don’t you realize you’re dead?'”

The specter of nuclear armageddon hums like background radiation on Orbital’s third album Snivilisation. As the cultural forces that produced the nuclear arms race ebbed with the fall of the Soviet Union, the Hartnolls, who grew up in the atomic age, never let their guard down. As members of Greenpeace, they kept their fingers on a pulse around the continuing dangers of nuclear missiles and human arrogance.

Snivilisation also came out the same year as the UK’s Criminal Justice Act. Among the law’s many provisions, it granted British police and civil authorities enhanced powers in blocking and shutting down raves and events with 20 or more people that played music with “a succession of repetitive beats” in public places. It literally outlawed techno and forced it back into nightclubs and was a direct attack on rave culture legislated in a climate of utter moral hysteria and generational division.**

For many UK artists, this was rich hypocrisy at a time when Western democracy was supposedly on a roll. For many, it revealed the insecure wall between freedom and Big Brother: The law seemed like a clear sign that power remained solidly in the hands of moneyed elites with a taste for war and family values. The renegade Spiral Tribe was public enemy No. 1: their uncompromising commitment to free party sound system culture, which had helped form the outdoor rave milieu that first inspired Orbital, triggered the backlash that contributed to the Criminal Justice Act’s passage.

So Snivilisation was in many ways, like The Prodigy’s Music For The Jilted Generation, a spirited retort and a call of solidarity with the larger rave community — an ammonite network of so-called “tribes” that averred to make a capitalism kinder and democracy truer to its highest ideals. The album’s press release framed up the stakes, stating the Hartnoll’s concerns, quoting the Belgian philosopher Raoul Vaneigem: “The history of our time calls to mind those Walt Disney characters, who rush madly over the edge of a cliff without seeing it,” it read, “the power of imagination keeps them suspended in mid-air but as soon as they look down and see where they are, they fall.”

“I was squatting in London then. We were homeless with our first kid,” Phil Hartnoll told Generator magazine’s David Newman, recalling his own struggles as a poor artist and what he felt was the persecution of New Age travelers — the hippie caravans that had kept the 1960s psychedelic ethos alive in the ‘80s and then fused with the ‘90s rave scene — describing in a way his own suspension in mid-air from a precarious cliff, what creatives so often find themselves gliding off, and then powering their own prospects and big breaks with the power of imagination, hard work and luck.

“By pure luck we managed to wangle our way onto a housing association,” he continued, sympathizing with the homeless. “If I was that age now, the only alternative is to get yourself a van and live in it….The travelers are being made scapegoats by the government. Their lifestyle is being banned...This Criminal Justice Bill is ridiculous. It’s like…oh, what’s the word for it?…” “Ethnic cleansing” his brother Paul finished. Bold charges, righteous ones even, that while idealistic and unrealistic by some votes, nonetheless capture the sense of alienation and anger that raves once allayed.

Sonically, Snivilisation draws that edge with a Graham Crowden monologue snatched from the 1982 satirical film Britannia Hospital, chopping it up in echoing counterpoint to the soft melancholy and uplifting beauty of opener ‘Forever.’ “We cling like savages to our superstitions. We give power to leaders of State and Church as prejudiced and small-minded as ourselves, who squander our resources on instruments of destruction,” Crowden rants, like clashing voices in the wind.

A sparkling gentle melody rounds in a mesmerizing loop, leading into Crowden’s fading warning: “While millions continue to suffer and go hungry, condemned forever, ‘ever, ‘ever, ‘ever!…” With that, Orbital drifts off the edge of the cliff, their imaginative deep keys holding us up, like steps on air or water, the beat dropping away, before it kicks back into a deep rocking groove amid lily-pad tones of electronic compassion, catching us as we fall, followed by interlacing melodies that arc overhead like falling stars or doomsday ICBMs.

The overcast continues with more literal rain sounds on ‘I Wish I Had Duck Feet,’ an eerie vision of tribal waddling and synth sadness complete with voice samples that evoke a circus à la P.T. Barnum — “Ladies and gentlemen, if everyone would please, gather around for the show. We’re going to have a free show…the Illuminated Man…the Sword Swallower…” Tribal drums pitter-patter like rain drops as foggy waves of synths billow ahead over the murky waters of tomorrow: “Shining through his body from within!” says the ringmaster.

The beautiful ‘Sad But True,’ featuring Allison Goldfrapp, shows the Hartnolls’ deft hand at more traditional songwriting while challenging the listener to swim through metallic dissonance, calling to mind the deep contrasts Orbital first burnished with ‘Planet of the Shapes’ on Orbital 2. It’s that brave use of tension, that spikes the senses and the emotions, revealing Orbital as masters of musical communion — Goldfrapp’s haunting vocals bringing an aching humanity to the snivels of the machines crying out for her divine forgiveness.

Goldfrapp would later embark on a successful career of her own, but her ghostly cries on Snivilisation lodged her deep in the unconscious of electronica fans. Her warmth contrasts with the colder and faster concerns of ‘Crash And Carry’ which seethes in dance floor rhythms and rattles, bumping in a wicked call and response of robots carrying out and fighting against the diktats of fascist rule. The album seems to burrow into the aural guts of our machine civilization, growing in harshness and sensitivity, each beat and note dancing on the edge of disintegration.

“I suppose these sort of things are what we’ve been trying to conjure up with music on this album,” Paul told Morton after he and his brother talked with him about everything from growing up with their mother addicted to doctor-prescribed tranquilizers, getting into animal rights, the clamp down on New Age travelers, and the ecological dangers of nuclear power. “Music that is inspired by the emotions created by these insane things that go on.” In other words, ambivalence toward technology and the future, while also providing an emotional salve crafted with technical know-how.

The deeper one goes into this Snivilisation, it almost seems as if the more abrasive, the more beautiful the music becomes. Tracks like ‘Science Friction’ and ‘Philosophy By Numbers’ round out Orbital’s eerie experimentation with surreal notes and angular drums. The former is a hypnotic whirl inside the engine room of human progress. It’s equal parts industrial and spiritual. The latter revels in an unease with institutional conditioning, sounding like a chorus of walruses and seals running amok inside a straight-jacket classroom. It’s otherworldly and quirky, revealing that the Hartnoll brothers studied up on the work of their peers, especially The Black Dog.

One of the album’s greatest triumphs comes next with ‘Kein Trink Wasser,’ which means “no drinking water” in German. A waterfall of piano keys sparkle in a loop of melodic shards, a fierce echo of minimalist giants Philip Glass and Steve Reich. The overflow of notes builds and builds until it drops away to stark chords that awake the moral imagination, while a breakbeat buttresses the drama with funky ballast, giving us minimalism that cuts through the New World Order of fast food and reality TV. Gorgeous and extreme, ‘Kein Trink Wasser’ is Orbital at their most inspired.

A concept album that challenges us to think and listen more carefully to the world around us while painting the sky with sounds seemingly beamed from the heavens, Snivilisation is perhaps Orbital’s most quiet and difficult album. It is a record of mixed emotions and relentless vision. Broken hearted, Paul and Phil Hartnoll, two brothers who believed in the power of music to change the world, were almost hellbent on memorializing that sometimes silly notion in a kind of sonic stone. So that ‘Quality Seconds,’ comes at us like a tidal wave of aggression, blurring the lines between hardcore punk and abstract techno, pumping its fists at oppression.

Almost exhausted, we come to the high point — ‘Are We Here?’ Considered by many to be Orbital’s finest composition, it again employs Goldfrapp on the angel council. “What does God say?” a distant male voice asks us memorably — followed by the musings of another voice, what sounds like an Aussie scientist in the astral wilds reporting back to us: “Are we here? Are we unique?” he asks earnestly. “Are we something utterly special in the universe? Or are we an example of many many civilizations that have been many many different life forms?”

Blending the scientific and the spiritual, the Hartnolls bring in a twirling jungle beat set to a lugubrious ska riff. Goldfrapp’s vocals whip about as if caught in a dust devil, her dervish moans opening up as ‘Are We Here?’ evolves into ever more frenetic drum scapes. But none of this prepares us for the delightful climax, which comes in a succession of brilliant waves borne on the broken rhythms of space and time. Questions ricochet in our heads: “Are we here? Are we unique?” Again it asks reverently, or is it mockingly, “What does God say?”

A reggae vocal counterpunches, “Warning! Warning! Nuclear attack!” taken from The Specials‘ song ‘Man at C&A.’ The washing machine snares and xylophones step up to Goldfrapp’s rising call and response in what sounds like a plea of “Being on a higher level!” Harp-like sparkles graze the rhythms until her voice bursts into what it seems some deem a wordless prayer for peace: “Here we are in your presence,” the lyrics machine wants to make us believe. “Lifting holy hands to You. Here we are praising Jesus. For the things He's brought us through.”

Answering her joyful coos in a kind of religious chorus, are high-pitched pipes that sustain like reflections in a waterfall — the true wordless secular hymn asking us to live up to the creeds we preach — trailing off to clock chimes and wakeful double knocks, before a humorous yet biting sample of an English family complaining about this new generation: “The prodigal son is alive and well and living in the front bedroom,” says the father. “We never see him, he treats this home like a hotel,” says his mother or sister. “You just can’t speak to him,” a brother adds, before the grand daddy roars, “He’s disgusting, long-haired, work shy, dirty lay-about, ought to be in the bloody army!” And in answer, Orbital simply repeats, “What does God say?”

Coming full circle from ‘Forever,’ the album ends with an epic ambient composition, ‘Attached.’ It wells like lapping waves from across the Solar System onto the shores of the Moon. A snarling synth snakes through a dream symphony in the heavens above, its sleepy gentle melody walking up the octaves, as a drizzle of light falls down from flickering stars. Skittering rhythms and a soft beat skip with an optimistic lift. Up, up, shining high, strings subside and the mind drifts to Orbital’s confident ride. Patiently, they build back the suspense, tensions rising to an operatic yell, before slipping us again into the euphoric current of life, floating us into a future of liberated minds. Without words, it seems to ask us a different question, “What IS God?”***

“Reshaping landscapes, remixing music biologically,” Ben Thompson wrote for MOJO magazine, reviewing a live show at Brixton Academy, “whatever Orbital are up to, their music creates an exhilarating sense of motion when you hear it in a big space.” That performance came on the heels of a historic show at the Glastonbury music festival that summer. The legend of Orbital’s live prowess grew immensely from this time, helping change how the press and rock heads in the UK saw techno music. It was indisputable that electronic music was capable of great power and artistry years before Daft Punk shifted the masses in America at the 2006 Coachella festival.

In 2019, looking back on Orbital’s mighty rise on the rift of Snivilisation, Andrew Harrison reminisced for The Guardian about coming upon that Glastonbury show: “Techno bled into drum ‘n’ bass into dream-like abstract reveries, and some 40,000 people roared the Hartnolls on, bringing to life the paradox of dance music: there’s nothing so human as machine music.” In a sense, rave WAS God. Not “rave” as the social style or fashion — though one of the more popular and funny t-shirts of the American rave scene in the ‘90s was “Jesus Raves” — but rave as the spirit of community, the energy people create when they come together and perceive solidarity and connection as a species — dance — as core to who we are.

“The government finds nomadic communities and the ideology of living in communities and co-operatives threatening,” Phil told Newman. “They want to break down communities because they are a much more powerful force. They’re splitting people up so that all you can do is think about yourself and look after yourself. New Age travelers and anything that hints at a powerful community force will be totally destroyed.” Civilization then as division, as segregation, as deprivation; without community, without a secular sense of common human decency — what raves spiritually provided at their best — then a digital society free-falls after all.

“We’re not saying, ‘Oh look at you lot’ because we’re all part of it,” Phil later acknowledged to NME’s Morton, while Paul continued with the theme of both futility and self-responsibility to the great community of the Earth: “I understand fully that I am part of it,” he said. “I throw away rubbish, I pollute, I waste water, and so on.” Touring the Russian Navy U-406 Juliett class nuclear-armed submarine off the shimmering coast of Helsinki, Finland, docked in its post Cold War slumber — apocalyptic nightmares of the past seemed not so far from the future. Songs ‘Attached’ and ‘Are We Here?’ are the gray glimmer of always being awake.

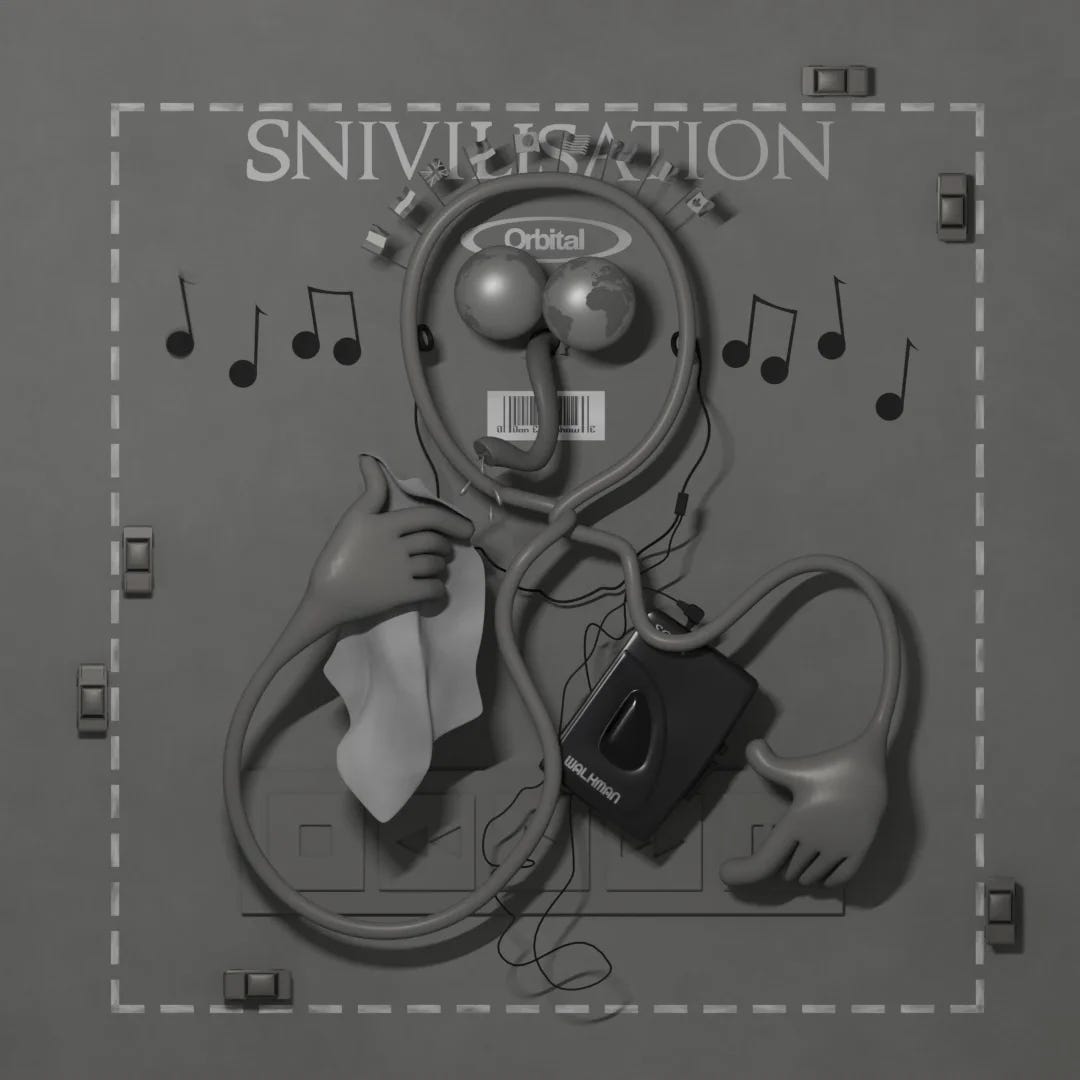

In the decades after Snivilisation, Western civilization encountered al-Qaida, many troubled wars and a Wall Street meltdown that left the global economy in tatters. But the Hartnolls were not just pointing fingers at governments. They were calling on all of us to keep the faith. The album’s sniffling cover art says as much. And its echoes into the conflicts and misadventures of tomorrow, loop us again and again.

With wires, headphones, mobile phones and robot electrodes, sticking from our heads, Snivilisation is a grand mirror for the age. The album’s inner sleeve art includes a witty picture of God on a clouded throne wearing virtual reality goggles. The message is clear: No one is free from the mirage, not even Him.

Track Listing:

1. Forever

2. I Wish I Had Duck Feet

3. Sad But True

4. Crash and Carry

5. Science Friction

6. Philosophy By Numbers

7. Kein Trink Wasser

8. Quality Seconds

9. Are We Here?

10. Attached

*The quote, attributed to MOJO Magazine, came up in some latter research on Snivilisation using OpenAI’s LLM. It seemed fitting to use one of the technological marvels of the 21st century to glean something new about Orbital’s techno-cautionary album and tale. But it turns out the clever quote is probably an AI “hallucination.”

Upon further research, including tracking down the exact issue that OpenAI told me contained the quote, MOJO’s 1995 August issue, I could find no record of the quote. Nor could I find it in other issues of MOJO from that time. Still, it beguiles, this strange hallucination between myself and the machine, and describes not only the album, but our new reality. Because ironically, it struck “truth” in a way with its words — though falsely so — as it described music that cuts both ways, like a double helix or sword.

So I have kept the quote nonetheless because it captures an important question that drives Snivilisation: If the truth cannot be perceived in the fog and the murk of virtual realities and techno delusions, then humanity may very well lose its way; wonders will unfold from new technology, but if Lady Justice’s blindfold is replaced with VR goggles, much like the album art that depicts God tuning out, well, then what?

Raoul Vaneigem’s quote about running off a cliff like a cartoon character that is suspended by its unawareness until gravity sets in, echoes the peril of ChatGPT spitting out a hallucination for a quote even when it was prompted specifically to provide actual quotes in the public record. I was caught myself in an illusion until I burrowed deeper into its origins, or lack thereof, echoing Paul’s nuclear dream too.

Taken at face value, I am perpetuating the cycle of delusion. But, like Paul’s dream, sticking with the quote along with this explanation, I believe, keeps us in the spirit of Snivilisation’s warning: Technology is seductive, but beware! That is, it is a nightmare as much as a fantasy. It folds in on itself — a double edge that animates the future.

**Not all generations were divided. In fact, John Peel (born in 1939), BBC Radio 1’s fearless DJ and purveyor of cool, had championed all of British rave’s artists: you can hear some of Orbital’s most fierce techno magic on their Peel Session of 1994, a continuous live performance that bridges their “Brown Album” with Snivilisation, incandescent in its brilliant twists and turns.

***As we all know, that future is still not here. But it’s the attitude, the mission, the dream, the belief, that carries. Interviewing Orbital in 2012 in Paris, Phil would tell me with great fervor in his voice:

“The same things concern us. It’s the whole disappointment in so-called civilization. We’re not advanced at all really. We haven’t advanced. While people are still killing each other, don’t even talk to me. It’s ridiculous!”