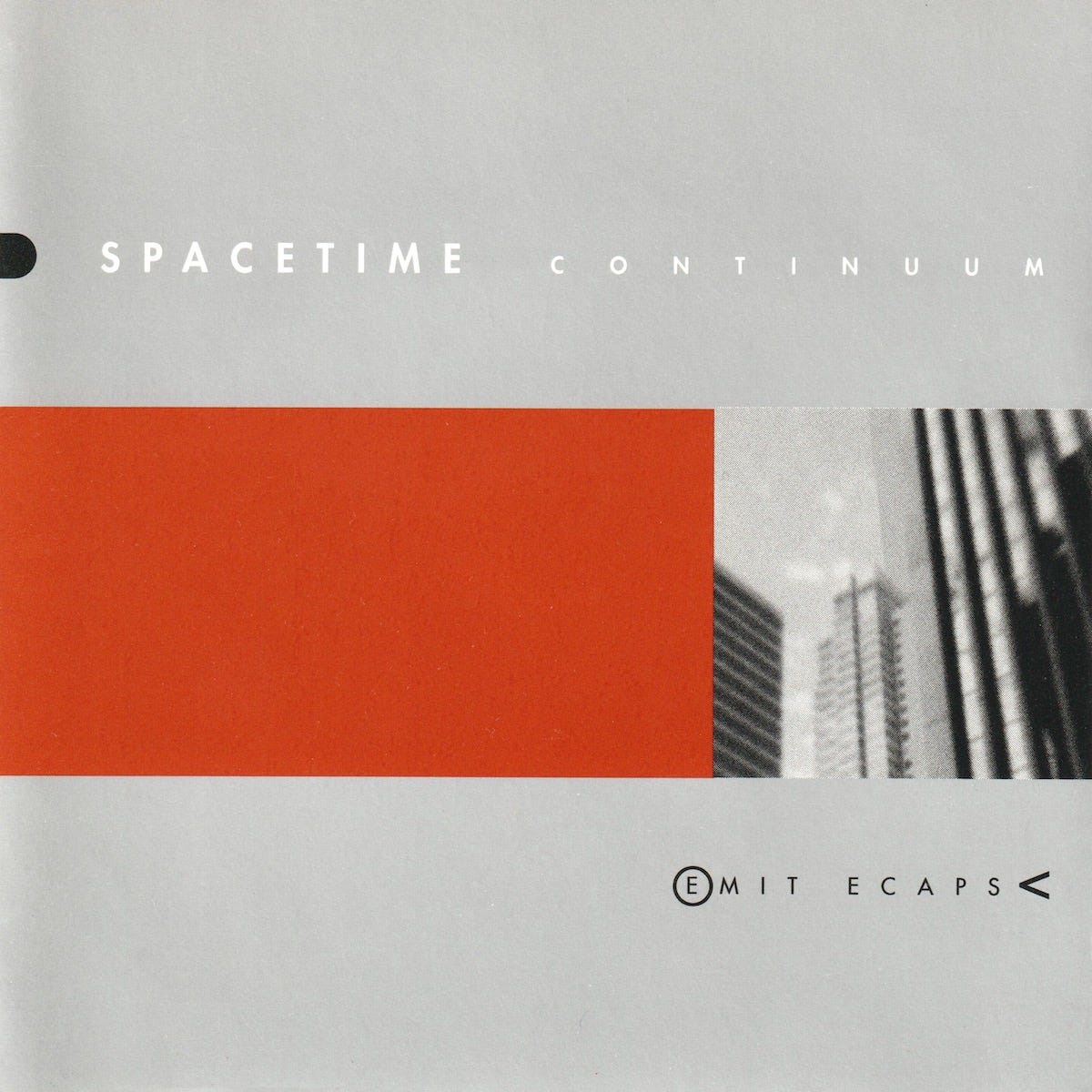

Spacetime Continuum - ’Emit Ecaps’

No. 39 in our Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s

The keys slide like a stair into the fog. And whomp! The drums kick in, and the synths walk up and down the years, climbing up the bluff above the sea. So plays Spacetime Continuum’s ‘Swing Fantasy’ on the extraordinary Emit Ecaps, an album of perfection at every turn, at every song. Released in 1996, Jonah Sharp’s masterpiece of techno jazz and blues house still sounds like it’s from some transcendent place out there on the horizon, beaming at the tip of a peninsula, where a city on a sandy hill could reshape the world with its acid love, computer thrills, and silicon mysterium…

It started with a great calm far from violence, though it had long tried to escape the Old World’s limits. “Anyone who would try and accuse me of being Mr. Ambient, or who says, ‘You can’t do this or you can’t do that’ can go fuck right off,” Sharp told James Matheson for Mixmag. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Sharp was over 5,000 miles from England. He needed space to help reinvent techno’s what and where. Obsessed with genre and fashion, London, had become a distraction. While still drawing inspiration from afar, in the Golden City of fog, time was at an inflection.

As Matheson observed, San Francisco, in many ways the city of the future digital revolution, was behind the musical cultural curve. Sharp, who learned to play drums at the age of 13, knew how to keep time. More importantly, studying jazz drummers like Buddy Rich and Gene Cooper, he knew how to swing it. As Matheson argued, “the city’s ambient, chilled out scene was based largely around new age theories and founded on the city’s ‘60s legacy of laid back, hassle free vibes.” The city of hippiedom was ready for time’s recursions — counterculture of the machine.

The continuum of the psychedelic revolution always finds its way back after sometimes moving away from the City by the Bay. “Tucked above an auto repair shop in the run down South of Market region of the city,” Matheson reported, the Londoner “Jonah Sharp is relaxing in a vast warehouse space that he combines as family home and headquarters for his experimental electronica label — Reflective Records.” Yes, reflecting the many paths of techno, he was connecting the beats in the California conversion point where Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, along with the Grateful Dead and British expats like Alan Watts and Christopher Isherwood expanded the definition of the human experience, in terms of art, philosophy and basic identity.

No wonder Sharp found himself in the Fog City, where he met his wife Billee, and partnered with Gamall Awad and Kirsten Caulfield to start one of the most innovative independent music labels in the world. In California, he could make music totally free from the pretenses and pressures of Europe’s rave hierarchy. “I’ve heard some artists get accused of genre-hopping,” he noted of the British press machine. “But I’m into a lot of different things,” he said, pointing out that same old hassle free California thing, from New World to New Age and onto pot and skateboarding. “I’m gradually working through all these ideas. No one should have to stick to one fucking thing, and I think it’s very boring when people do. I mean, do I have to do the same music all my life?”

In the 1990s, San Francisco was a beacon to people who craved to do what they wanted. Long before the money chasers and the start-up gold rush reached its slick fever pitch, artists from around the world came to the Golden Gate City to architect a new frontier that would open up human consciousness, not just the wallets of venture capitalists. They were misfits who came to California and its northern Bay to push the rhythms and grooves of house music to new heights. Simmering in the aftermath of the “Disco Sucks!” backlash — much of it arguably directed at minorities and gay culture — the home of sailors, whalers, miners, prospectors and their Chinese rail builders was always fertile ground for new ideas, from Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas’s American Zoetrope film rebels to Patrick Cowley’s synthesizer dreamland of ‘Mockingbird Dreams’ and groovy ‘Somebody to Love Tonight.’

Across the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge was the Berkeley-fueled Don Buchla modular synth movement, where the likes of Suzanne Ciani first launched her storied career, crafting her cascading Seven Waves along with a magical panoply of 1980s pop advert music and sound effects. In 1983, the Bay Area-based independent Fantasy Records released Cybotron’s techno-blues blueprint, Enter. And as the legendary Castro District heated up and then cooled during the AIDS crisis, the stalwart civil rights activism of visionaries like Marlon Riggs used dance (on his Tongues United), along with the sounds of house music, to convey a stronger solidarity against inequalities and injustices in race, sexuality, and civil rights.

It was in this milieu of ferment and tragedy that the ‘90s dawned on the San Francisco Bay as the rise of Silicon Valley began its blazing ascent in the form of the Internet. An underground fire was burning right alongside it, perhaps even deeper within it — rave — by way of Chicago’s own gay disco resistance, and Detroit and New York adjacent. While acid house pioneer Ron Hardy, who inspired DJ Pierre and Phuture’s fiery ‘Acid Tracks’ breakthrough, had spent some time in Los Angeles, imbibing its own libertine sounds and byways before returning to his hometown to play his Yang to Frankie Knuckles’ Yin, the “acid house” revolution that swept the UK beginning in 1988 combusted with the psychotropic empathogen MDMA. Or “ecstasy” as it was rebranded by savvy Dallas club inebriates and dealers; its flashpoint was San Francisco by way of Dr. Alexander Shulgin’s rediscovery of its old chemistry.*

At the edge of the Pacific, this incendiary wave pushed back west into the unknown, as a new generation of dreamers came of age: Sunshine and Moonbeam’s hippie and Haight-Ashbury inspired Dubtribe Sound System, forming its long alliance with the San Francisco native son DJ Doc Martin (LA’s house music prophet); Zoë Magick’s Young American Primitive and Single Cell Orchestra; along with the likes of Kim Cascone’s own Silent Records and his Heavenly Music Corporation; the funkier stylings of Jim Hopkins’ Twitch Recordings; the mystical house of Wicked with transplant DJs Jenö, Garth, Markie Mark and “English” Thomas; the heady and progressive DJ Galen and Solar project, Sunset Sound System; the soulful and rebellious Hardkiss Brothers; the high-rolling Funky Tekno Tribe; the classy explorations of Charles Webster; the Baroness and her Electric Manor.

The author and psychic traveller Douglas Rushkoff would immortalize this Bay Area hallucination in his books, Cyberia: Life in the Trenches of Cyberspace and his fiction novel Ecstasy Club. The tech chronicler Wired magazine and the headier Mondo 2000 would both birth in this 1980s-to-1990s mass computer explosion. While feminist and influential scholar Donna Harraway, ensconced a little south in redwood-ringed Santa Cruz had articulated this spiritual earthquake with her groundbreaking 1985 essay, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” which cleverly illuminated humanity’s irreversible symbiosis with machines; no amount of light could restrain the human appetite for escapism and power; ten years later, teens throughout the Bay Area would be tripping out to the trance mixtapes and Cybertrance parties of DJs Mars and Mystre’s Frequency 8, several of them promoted by the email lists of Brian Behlendorf, the mastermind behind Hyperreal.org and the main inventor of the Apache Web server.**

This is all to say this was not some fluke or footnote on the future that came to pass. It was a wave, and simply not well understood, documented or perceived in LA, London or New York City, though its emanations were without refute. It took a Scotsman then, Jonah Sharp, a jazz drummer who had once jammed with The Shamen’s Mr. C in his more unyielding DJ guise, to write a tone-epic that electrifies its holographic image from then to now, and into perpetuity: Emit Ecaps is a timeless labor of love, a love letter from an immigrant from the other side of the Atlantic come at last to the so-called final frontier of the wayward and the determined. Even its album artwork of silvery grey, maroon red and its glimpse of sun-flecked buildings, speaks to his Scottish-bright sympathy inside San Francisco’s sea-battered symphony.

"Ambient is all about creating an attitude, breaking down genres or communicating with the listener in a deep, spiritual way,” Sharp told the San Francisco Chronicle, in 1995, while playing at the Gardening Club at the Caribbean Zone on Natoma Street. “It’s experimental and abstract. When you’re playing music for the dance floor, you have a specific task. But there are no rules or definitions in ambient music.” It was ambient’s sense of freedom, its amoebic amorphousness that allowed him to play techno music in countless permutations and evocations. It was a gateway sound, calling to the city’s college students, trendy professionals, and club kids, The Chronicle reported, “staring at videos of landscapes as viewed from the sky.”

Released on Astralwerks, which also released the SF-based Freaky Chakra’s excellent Lowdown Motivator, Sharp’s album — spelling space time reversed — is itself a monk-like koan of wonder presented at the peak of Tech’s optimistic dreamtime. In fact, his most famous experiment, Spacetime Continuum’s Alien Dreamtime with mycologist Terence McKenna, the psilocybin theorist who averred that human consciousness, intelligence and civilization owed its initial spark to magic mushrooms, was just exploring the tip of a much more interesting iceberg. Sharp’s debut album, the ambient ocean of Sea Biscuit, revels in sparkly electronics, emerging from his missionary zeal for live performance and his spectral Reflective Records label aesthetics, tuned in chill rooms and Reflective’s South of Market office — its ‘Floatation’ an especially inspired and fierce navigation into the future.***

“When I got here, there was this huge influx of Brits, and Irish, and French – a European invasion,” Sharp told Matt Anniss in 2016. “It was fairly small in the grand scheme of things — between 50 and a hundred people — but all these people started doing parties. It was like we were importing rave culture into America. The first month I was here, I got a residency because I was a British DJ. That was all it was! ‘He’s from London… he’s massive.’” Laughing at the exotic fascination Americans had with Euro-types at the time — with no benefit of social media — Sharp didn’t take it for granted, working hard and fast to bring the rave experience to the Bay. Within a month he was teaming up with Genesis P. Orridge to help open their Psychic TV shows. Hence the Spacetime Continuum name was born as Sharp continued his vision forward.

Formed earlier in the intense blaze of the London rave scene, the Spacetime Continuum ethos was greatly inspired by the Spacetime chill parties that Sharp, Mixmaster Morris and friend Richard Sharpe (ex-Shamen keyboardist) threw in and around London, its name taken from Richard’s alternative clothing store name (which also supplied the hologram fabric that bathed the walls of their events — inspiring the hologram labels on Reflective Records’ future vinyl releases). “The parties were pretty small to begin with,” Sharp reflected to Anniss. “The first one, there was only about 50 people there. It was so much fun, because it was in such a cool space in Limehouse in East London. We put these parties together every couple of months, until the last one, which was completely insane. Everyone who was anyone showed up. Björk was there. I’ve no idea how she found out about it!” And so that blaze was highly ambient.

Richard then moved to San Francisco; Jonah followed, joining him for a gig and deciding to stay. London had lost its sheen for both friends, after their Spacetime party phase. Sharp was near penniless in London, and in San Francisco he found a hardcore artists community, along with other British exiles, that were committed to a new kind of freedom, a radical freedom that resonated with the radical sound waves he was beginning to craft and shape. In addition to Björk, attendees Jimmy Cauty of The KLF, The Shamen, and the recycled art performance group The Mutoid Waste Company, reflected the power of Spacetime, providing powerful memories for a continuum from London to San Francisco. In its South of Market headquarters, Reflective represented a kind of holographic mirror between the two cities.

“Sometimes San Francisco is like a city of ghosts,” wrote Tony Marcus for a compilation dispatch from North America, titled Trance Atlantic in 1995. “The first buildings you notice are the old houses, apparently designed by Lewis Carroll on LSD, wildly pink and other-colored, falling skyward with high pillars and fantastic planes of glass.” Marcus describes a city still suffused with the Acid Test legacy and yet filled with crack-heads, data-heads and ravers in overlapping proximities. “Since I came here,” Sharp recounted to Marcus, “I’ve met some of the fucking wildest people I’ll ever meet in my life. Out-there people, colorful people. I know weird underground people, computer-heads, a lot of cool people. Everybody on their own little trip.”

It was that cosmic spirit of creativity that Sharp wanted to bring and then found in California, applying a more mellifluous and open-ended approach to clubs and social gatherings. With Reflective, he sponsored the more experimental techno and ambient of Single Cell Orchestra, Vulva, Velocette and Kid Spatula, including the drum ‘n’ bass of Subtropic. But it was Spacetime Continuum’s “chill” or “deep chill,” as he called it, that made the biggest ripples at first, especially his Flurescence E.P. with its deep synthesizer pads on the title song and the infinite bloom of ‘Transmitter.’ Taking influences such as Cabaret Voltaire’s live shows, Aphex Twin’s early ‘Analogue Bubblebath,’ Detroit techno classics like Derrick May’s remix of ‘Sueno Latino,’ combined with his jazz background and the deep house of Larry Heard — the Spacetime Continuum sound emerged naturally, confidently, and individually.

So that by 1996 as electronica reached its first popular peak in the United States, Sharp was pushing his more chill mindset back into the main room. Ever a deft man of rhythm, Emit Ecaps showcased his utter ease with drums as much as keys. The album opener ‘Iform’ scintillates like his compositions before but two minutes in rolls with a dubby bass line, synths and hi-hats ricocheting around a bending sonic universe. Its song title even prefigured the ‘i’ Apple product lines of the iMac, iPod and iPhone, Sharp’s ‘I’ forming a world of infinite possibility. (Perhaps Apple’s English design director Jony Ive was listening.) Sharp throws down an even more dynamic and forceful manifesto with ‘Kairo,’ a shape-shifting nearly 12-minute epic of synth siroccos, gentle plucky keys, in a deep call-and-response with stand-up bass morphing like a sand-worm under the desert floor, skittering percussion firing overhead, the earth booming — a mesmerizing cyclone of brawn and beauty.

“I’m really interested in bringing new sounds on to the main dance floor, but the music still comes from the heart — I never put stuff out unless it means something,” he told John Richardson for Urb magazine in 1996. “The album was finished in three weeks, but I tend to record quickly,” he described of his fluid and improvised writing style, a free spirit and mien that can be heard throughout the continuum of the album. “I get all these ideas together and then do this sort of recording process where I’ll spend three weeks, non-stop, just putting stuff down. The rest of the time is spent just mucking about collecting sounds.”

The space-time ethos swells to full on ‘Simm City,’ hinting at the simulation obsession of the computer world rising around Sharp in the ‘90s, from the SimCity video game franchise to the growing sense that “we’re living in a computer simulation,” a feeling advanced as a possibility by the philosopher Nick Bostrom and made famous by Silicon Valley robber baron Elon Musk in the 2000s. But Sharp’s simulation is a romanticist’s vision, not a techno industrialist’s, infusing his sim with pathos.

Darkness and regret are not the emotion though, but an open-minded resilient optimism: ‘Funkyar’ is this attitude and soul to a note and a beat, a shimmery elastic freak-jam with swagger, slow-mo, yet strutting from Mission to Union Square; ooze of smooth, stepping over the threshold into tomorrow, the columns of data and the beep of its traffic no match for the galaxy of groove growing deeper inside us. It is like a Magyar marauding in the valley of computer winds, the hunger of our artistic past driving common ground, past flashing glimpses of a tempting imperial future, and riding instead into the promise and the heart of the timeless.

This feeling is no truer than on ‘Swing Fantasy,’ which in many ways marks the halfway point of the album emotionally, a gateway within a gateway itself, its first half an echoic kalimba finger piano, plucking over dreamy snaking bass, followed by phosphorescent keys, dancing up and down the octave, stabbing at sleepy souls lulled by technology’s hypnotic burbling. Then right at the midpoint, the beat drops out and the melody leaps up the diatonic scale to a higher universal eight. The harmonies swirl above. And then? Glissando, the beat returns, Sharp propelling us onward with a metronomic swing under and over the metropolis and on through the Golden Gate.

The grey clouds dissipating to an invisible sun, ‘Out Here’ is the techno twin to the house magic of ‘Swing Fantasy.’ Reminiscent of Autechre and B12, both peers that Sharp deeply respected, it is morose even at first, cerebral and Detroit-minded like their early works, but once again opened up and freer; that turn, that migration of sound and experience coming in the song’s second half; where here becomes a restless rummaging walk into a robot future. Autechre along with Carl Craig and Higher Intelligence Agency would contribute creative and wily remixes for the companion Remit Recaps album, an electronica landmark in its own right.

As if feeling the controlling oncoming power of “Big Tech,” Spacetime Continuum zips into ‘Vertigo,’ a tentacular Jell-O-like wonder, its melodies spilling out like moray eels, drifting us deeper into the depths of time, the Sun shooting rays down to us through the ocean waves high up, the light washing over tired thoughts and resurrecting the spiritual core drowned in modern life’s mechanical onslaughts. So alive, ‘Vertigo’ is blade-like in its penetrating splendor, one series of waves of keys and synths move after another, holding our breath, then bursting with a compatriotic fervor.

‘Twister’ and ‘Pod’ form the next two statements in Sharp’s trio of ambivalence. Electro ambient classics, all three speak to a storm ahead as well as calmer waters. ‘Twister’ spins in a mostly shapeless becoming, its sub-sonics equally subway and submarine, the destination flickering in momentary doubt and introspection. (David Moufang AKA “Move D,” one of Sharp’s many international collaborators, takes his liberating remit into dancier and drummier terrain, turning it into a long lost Deep Space Network classic on Remit Recaps à la DSN’s expansive Big Rooms.)

Happier airs rise on ‘Pod’ as Sharp seems to bring us back onto steadier shores. Perhaps we are out somewhere in outer space or simply sipping coffee on a space station as the sun peaks over the Earth’s curved sphere: there’s always a need for a lifeboat or an escape pod, and the seeds of a better tomorrow will lie in the heart that beats pure, and assures all the believers and the disenchanted that the means to our end is still surely in our own hands. For here is a composition that contains in it the shuffling joy and anxiety of an exciting future, its carefree yet caring groove a reassuring synth pop-tinged effervescent whirl — a robotic voice at once a juxtaposition and a re-assimilation of our very own human grandeur.

That cyborgian torque of ‘Pod’ leaves us at last standing before ‘String of Pearls,’ a breathtaking beauty that floats right up there in the annals of ambient greatness with Mixmaster Morris’ own ‘Waveform’ and his immortal remix of Barbarella’s ‘Barbarella’ — Sharp’s spin on the two old friends’ passion for quiet adventure and startling ardor, chimes into the deathless, its answering resounding reflections shining over and at us through distress like the rescue signals of God, whether God be a conscious being or simply consciousness rising up through us and out up into the universe. Mixmaster Morris rightly used this marvel to close his hopeful era-defining Morning After mix, drifting, drifting, drifting into the infinite, its ‘90s waves fleeting into the distance.

And what of that era? It was not perfect despite the millennial nostalgia. Like almost every generation, the X or what Urb once called the “E” generation — as in ecstasy, and therefore E-caps — the young at heart bucked at the yoke of the status quo so that the hackers and the upstarts of the Web, who grew up in the ‘90s, saw too a chance to “move fast and break things,” though the first generation ravers were breakers in the dance sense, more than in the programming sense. In time, the impatience to usher in the future created a rift, and then a canyon between the generations and all persuasions, so that persuading became a zero-sum game seemingly obliterating the pluralism that had once been the ethos of rave.

Elastic, sharp, renewing — Spacetime Continuum’s magnum opus remains one of the greatest achievements of that ‘90s electronic music revolution. Its indispensable trait and miracle is that it perfectly captures an inner human-machine balance. Synthetic and organic, his sound negotiated the boundaries of a new transition between the digital wave overtaking his adopted home and the analogue world that had given sustenance to the Bay Area’s philosophers and artists. The wilderness and quiet townships encircling its waters both the playground and refuge of the rich and a generation of information warriors, represented the contradiction inherent in the computer revolution’s social code — that wealth still flowed to the connected.

“This is where all the computer heads come for lunch,” Sharp told Marcus with ambivalence toward the emerging techno elite. “They all sit around and talk about what’s new and what they’re going to be able to do next with the new software. But they don’t actually seem to do anything.” Of course, he knew they were reshaping the world. They only seemed to be doing little or nothing. Marcus perceived Sharp’s wry sense of humor. “Maybe they don’t but just across the bay in Silicon Valley a whole new set of futures are growing,” Marcus pronounced. “Real techno cities built from zeros and ones, virtual reality, Apples and Microsofts. And above our heads are the corporate skyscrapers and banks that fund this future with digital cash.”

So many of San Francisco’s techno dreamers would find themselves on the perimeter of this epochal shift as power transferred from their conscious imaginings to a faster space controlled by Wall Street and its more privileged masters, the entrepreneurial self-starters riding the wave of tech bros and IPOs. San Francisco had always been the repository of westward ambitions, and as the great blue slate of the Pacific still loomed where the Sun set, Spacetime Continuum’s vision of a more humane and humanistic symbiosis with machines, faded in the memories of the city that had forgotten its own origins in the frenzies of Burning Man and the big silicon rush.

Even so, there was the other dimension of social connection that Sharp and Morris had envisioned with their Spacetime at the beginning of rave’s Big Bang: an elemental and magical part of our DNA that tempered the fevered rush of the world’s pummeling techno oars. As Sharp would explain to Anniss 20 years after Emit Ecaps entered the world, in 1991, he had perceived that things were accelerating faster and faster; that people were realizing the possibilities of where they could go creatively with the blueprint of electronic dance music. Naturally, he had reasoned that that is why ambient chill rooms were needed: an awakening to the instinct to slow down.

“You had to have it,” he told Anniss, “because the music was so fucking intense that you had to go and chill out somewhere.” That is why Sharp brought a cooling balm into the dance-floor continuum, where the matrix of the future was being imagined and even embodied. He reached out to like-minded artists around the world, like Tetsu Inoue, releasing the classic Instant Replay in 1997, and Moufang, who collaborated with Sharp on the legendary Reagenz project; Germany’s Pete Namlook recruited Sharp for the influential Alien Community albums, the epics ‘A Long and Perilous Voyage’ and ‘Interdimensional Communication‘ showcasing incredible work.

Critically acclaimed, Emit Ecaps was indeed a kind of deep breath before the plunge. Like ‘Out Here’ and ‘Swing Fantasy,’ it represents a transversal truth where everything seemed to come together and then break apart. While his innovative REALtime E.P. a year later took a bold swing with the unique ‘Neoteric,’ featuring MC Girao rapping in Japanese, showing Sharp’s continued interest in the Pacific Rim and its global points of view, his third album Double Fine Zone of 1999 was met with indifference and the dissolution of Astralwerk’s first bullish phase of market growth. Featuring the saxophone playing of Brian Iddenden, and Damien Masterson on harmonica, retrospectively it is a lost classic of tech-jazz brilliance, worthy of the same breathlessness that fusion fans greeted Squarepusher and As One.****

Equally adept at a drum set or at a Rhodes piano, or behind a bank of samplers and synthesizers, Sharp is one of techno’s truest visionaries. In more ways than foreseen, the intense energy unleashed by the microchip sends changes in big waves, the fog growing thicker by the day — and yet a flame beckons the lost through the distant murk on Sharp’s greatest work. The more you listen, the sharper it becomes.

In the age of robots, artificial intelligence and antisocial algorithms, everyone searching for space and time and peace of mind, Emit Ecaps harkens back to a sweet swing reality with a reflective humanity. It emits a warmer light — a sensitivity to the beloved community — calling us back to a gentler might.

Track Listing:

1. Iform

2. Kairo

3. Simm City

4. Funkyar

5. Swing Fantasy

6. Out Here

7. Vertigo

8. Twister

9. Pod

10. String of Pearls

*The importance of MDMA’s role in the popularization of electronic dance music is well-known and well-trodden. While I do not believe it is in any way critical to one accessing the potentialities and power of rave, for many it was and apparently is. Nonetheless, Shulgin’s key role in the history of the psychedelic movement is indisputable. The Starck Club in Dallas, Texas, is part of that story. For those interested in this chapter on ecstasy history, I recommend starting with a TV documentary Peter Jennings produced not long before he passed away.

**Brian Behlendorf was a key figure in the expansion of the Internet, being the primary designer and developer of the Apache Web server source code, the most popular web server software in the world. His hyperreal.org was also a critical resource of intellectual exploration around rave and electronic culture in the ‘90s.

***Despite some of the maximalist language in Terence McKenna’s spoken-word “raps” on Alien Dreamtime, some of the ideas and concepts are still thought-provoking decades later. It captures a moment in time, especially in terms of psychedelia and California’s unique brand of techno-escapist idealism.

Sharp’s music on ‘Archaic Revival’ is especially powerful, its use of groove and melody is a quintessential display of acid house optimism and exhilaration. The instrumental ‘Transient Generator’ is also a highlight, influencing the Future Sound of London’s classic ‘Cascade’; and the 20-minute plus ‘Timewave Zero,’ with McKenna’s pontifications on nature, epigenesis, and hyperspace, is quite compelling.

Some may also complain about McKenna’s voice, but like Rush’s Geddy Lee, the content of the delivery and the energy behind it is still effective for those willing to withhold their more judgmental tonal instincts. One passage is particularly evocative from ‘Archaic Revival,’ even though I do not personally advise the use of psilocybin to achieve enlightenment, given it can trigger adverse mental states in some and is still not well understood, and because it should be treated with the utmost care. Mushrooms aside, I do find McKenna’s articulation of spiritual growth apt:

“The twentieth-century mind is nostalgic for the paradise that once existed on the mushroom-dotted plains of Africa, where the plant-human symbiosis occurred that pulled us out of the animal body and into the tool-using, culture-making, imagination-exploring creature that we are. And why does this matter? It matters because it chose that the way out is back, and that the future is a forward escape into the past. This is what the psychedelic experience means. It's a doorway out of history and into the wiring under the board in eternity.”

”And I tell you this because if the community understands what it is that holds it together, the community will be better able to streamline itself for flight into hyperspace. Because what we need is a new myth.”

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of McKenna’s mystical description of the human experience is his use of the computer metaphor of circuit boards or motherboards to describe reality and spirituality. It feels prescient.

****In fact, the tradition of more organic sounds, including the saxophone, was a key component of San Francisco’s rave vibe, whether we’re talking Mephisto Odyssey’s Dream of the Black Dahlia and Catching the Skinny, DJ Rasoul, or Aquatherium’s Full Moon and Bonny Doon. Its acid jazz scene was also very strong with the likes of Greyboy and the tried and true record label, Ubiquity.