The story of The Advent traces several touch-points of European techno. Cisco Ferreira, the main driver of the group, was originally from Portugal’s small archipelago of Madeira off the coast of Africa. After finishing high school, he joined London’s Jack Trax label, where he cut his teeth as a studio engineer on sessions for Chicago house legends Marshall Jefferson, Larry Heard and Adonis. In the early 1990s, Ferreira relocated to Belgium’s R&S Records, where he co-wrote much of CJ Bolland‘s acclaimed album The 4th Sign, including classics ‘Camargue’ and ‘Mantra.’

It was back in London where Ferreira would meet Colin McBean, a talented DJ with a mean record collection. The pair teamed up with Keith Franklin of Bang the Party and formed the KCC collective, launching the infamous Confusion parties which spewed house and techno through a massive reggae sound system. McBean brought key ingredients to The Advent’s high-tech swagger. He was West Indian descent and steeped in island soul. He had a sixth sense too for swing and helped focus their partnership on what he called “hard funk.” Today, he is better known as Mr. G.

While Ferreira was the studio wiz, McBean was the “hard funk” tastemaker. He brought a DJ sensibility that he picked up as a kid in Derby going to “shebeens,” underground Jamaican sound system parties, heavy on the reggae and the dub: “Music is like a Picasso; less is more. If you’ve got eight amazing sounds, it can’t be bettered. Also, I’m a Reggae man. When I listen to old dub, from the fifties and sixties, just six channels on a crappy mixer, and I hear the weight and sound, I was convinced that was always going to be my way,” he told the journalist John Thorp. “That’s the way I work in the studio … Eventually I end up with a sound and a set where every single sound counts.” Which is to say absence is as important as presence.*

“We’re street people. We like it funky and swinging,” Ferreira told Generator magazine’s Oliver Swanton in late 1995 just before they went into production on New Beginnings. “It’s in our blood,” McBean echoed. “He’s Latino and I’m a Black man, so the swing is inborn!” So as not to let the point fade amid the conversation, Ferreira hit it one more time as key to their identity. “Seriously though,” he added, “at the core of every track, no matter how fast or hard, there should always be a nice swing and a groove that really rocks you.” And by “swing,” they meant the drifting and rocking across, and on and off the beat, or the tug of the beat, just so, that elastic space between notes — percussive or melodic — the trance of dance and its identity.

Deep down in the machine is that human thing: the blood, sweat and tears of laboring and hammering the metal rails and nails, the chain gangs, the shouts and hollers of workers and slaves, across oceans, on deltas and islands. “I would defy any man not to hear in good techno there is a heart and a swing and a soul,” McBean told Mixmag’s Dom Phillips. “No matter how hard or how slamming it sounds, there’s a funky heart and swing rocking the soul out of the middle of it.” The Advent’s clear perception of techno’s essence — its human soul — is what made their mission a profound and precise articulation of rave’s arc, invoking in Phillips the old record pressing plants of Detroit’s Motown to Europe’s pursuit of awesome club sound.

In April 1997, Mixmag caught the duo right before their New Beginnings release. Journalist Nick Jones focused on that molten swing inside a metallic shell. “The first thing about Cisco is he’s the man with the ears. I’ve never met anybody who hears things in that way. He’s the crazy one,” said McBean. “He’s the mad one. And he’s fucking patient. We get any new machinery in here, no manual, nothing, my man’s there tweaking it hours on end.” Jones argued New Beginnings was not so much progression as consolidation of their sound. He described it as “a stripped down, thudding, racing, dark techno marvel.” Like Phillips, who interviewed The Advent earlier in 1995, Jones was picking up on the hardcore dynamic between the two; where Ferreira provided the electricity, McBean provided a human flair and zeal.

Ten years older than Ferreira, McBean gave The Advent some real ballast and its gravitas — its world-weariness. Jones believed this group “identity” was a secret motivator. In a way, McBean and Ferreira were outcasts. Ferreira grew up in West London after his family moved to England when he was five. He was a self-described “sci-fi freak” and graffiti tagger. McBean was once a chef, working in kitchens all over Europe and later studied fashion, making his own clothes and soundtracking various fashion shows. They met in a sound engineering class; “techno is where they exist,” wrote Jones. Their live shows were “incendiary.” “If we didn’t rave hard in the early days, we’d find it tough now,” McBean explained of their relentless touring. “But as soon as you get on that track again, you’re like, ‘Yes, this is the fix’ and the energy comes back.” Riding long nights, back in the studio, they took that fervor deeper.

The adventure of The Advent began then, from a place of both friendship and an expertise that was both uncommon and natural. First, they took an assignment from label mates Salt Tank, producing early examples of dreamy-dreamy, ambient trance, ‘San Francisco HM’ and ‘La Rêve De Beatrice,’ on Salt Tank’s ST4. Laguna Calorado mini-album from 1994, apparently inspiring Paul Oakenfold to kick off his “dream house” movement a few years later. Signed to Internal Records, owner Christian Tattersfield gave them the full-throttled support of an underground music lover: several E.P.’s followed, including the excellent Infrared, their maiden voyage, its ‘Infrared’ shredding the air as if it were unleashing the molten heat deep inside machines, its ghostlike metallic riffs erupting and lashing with tongues of fire.

Previewing the paths and zones of their first album, Elements of Life, a rapidly released run of techno monsters — the rat-tat-tat drums and robot ribbit croaks of ‘Unknown Freakquencies,’ the aggressive acid auroras of ‘Anno Domini,’ the spilling splintering spurts of ‘Missing Time,’ the unrelenting ravager ‘Mad Dog,’ and the bold tribal shattering freakout of ‘Bad Boy’ — tore a hole right through the London techno underground. DJs like Darren Emerson and Detroit techno master Jeff Mills dropped The Advent’s cuts into their sets and featured them on classic mixes like Emerson’s Psychotrance 2 and Mills’ Live Mix At Liquid Room, Tokyo. Appearing on over 130 mixes over the years, The Advent were a mainstay of the global dance floor of the 1990s, often bashing at 145 beats per minute, and doing double damage, slowed down into the 130s and 120s with Ferreira’s production prowess second to none.

Just two years after their debut double-album Elements of Life, an ambitious effort that took its cue from the angular assaults of early Underground Resistance and Plus 8, they returned with the muscular New Beginnings. The Advent’s update was turbo-charged and anchored by Ferreira’s technical brilliance, giving their sound a tough-as-nails edge over the competition — electro was the flashpoint for their new direction — glimpsed earlier on tracks like ‘Spaceism.’ But now Ferreira and McBean fused tighter arrangements with crackling bruising beats and sneaky sonics. The warped ‘Funkage’ tricked the mind with explosions of bass. Its twisting rhythms tugged with a terse and irresistible riptide. But ‘Stassis’ took the prize — its cavernous drums whipping under rising strings of sine-wave spiritualism. And the delayed end of ‘Stassis (Part II)’ still remains one of the most brilliant goodbyes of any electronic album. To their heroes across the Atlantic, from Juan Atkins to Drexciya, it was indeed a welcome salute.

Electro — going back to Cybotron and Afrika Bambaata — was the crossroads, or elastic expanse, more accurately, between the breakbeat and the metronome, the tension and release of the machine as first envisioned by Kraftwerk. The Advent were resolutely techno, greatly inspired by Mills and Underground Resistance, but like their heroes, they were equally moved by the roots and routes of hip hop, jazz and rock ‘n’ roll by way of funk and soul. Electro-techno then was the zone that Ferreira and McBean explored and mastered, as can be heard on ‘Call God’ and ‘City Limits,’ Elements of Life standouts that loosened up the potentials of New Beginnings. Critically, those beginnings included dub reggae too and Latin freestyle — the movements that informed their youth and childhoods: bass and beats galore.

“My first ever ‘main’ go to music was electro music, or Latin freestyle and their amazing way of the tape cut and edit,” Ferreira explained to Fifteen Questions. “This form of cutting music, I was obsessed with, and it led to my first ever productions being in this style of music.” But while The Advent’s style was highly technical in nature, harkening back to the edits and cuts of legendary New York freestyle engineers Omar Santana and Jose “Animal” Diaz, Ferreira also believed that technological precision had to be balanced with the “swing” of the human.**

Island to island, soul to soul, McBean and Ferreira drifted through the vast possibilities of the techno-ocean. McBean traced his heritage to the Caribbean, Ferreira to Madeira, which was once a hub of the Atlantic slave trade. That mix of European and African journeys, tempered by the echoes of America, is subtly hiding behind the hard machine shell of The Advent’s sound. For when you start to pry it open and listen to its human heart, you find within it a red-hot tension, not really between The Advent, but the currents and waves and storms of history that the techno revolution buffeted and indeed lifted them up with. In 1998, a year after releasing New Beginnings, after Tattersfield departed Internal, its parent label Polygram ended their contract. All of a sudden, they were a bit lost and adrift.

In fact, The Advent had been on such a tear that New Beginnings was ready for release eight months before it finally hit London dance floors, much to their chagrin. By then, they figured it had already missed the moment. “Polygram just didn’t know what we were about, or where we were coming from,” Ferreira lamented to Mark EG for Wax magazine that March. A few E.P.’s made their mark during that hold — like Insight 02’s snarling sneak-attacker ‘West Wave’ and a single version of ‘Stassis,’ spelled ‘Stasis,’ cracking open like the red lava seams in a caterpillar of magma: belching, blistering, blazing. That sizzling genius also appeared on Retreat and Standers and the E.P. of the same name as the album, New Beginnings — each featuring inspired numbers, like the mesmerizing, robotic call-and-response of ‘Electrapour,’ the primal, extraterrestrial calls of ‘Real Timez,’ and perhaps, The Advent’s best all-out breakbeat bender, the heady electro funk of ‘Future City.’

They were unstoppable. When Wax talked to them that spring — after they had departed Polygram and FFRR — they were already busy plowing ahead. “Much of the time, Colin just reaches across the keyboard and finds the groove I’ve been looking for,” Ferreira said of their dynamic. “It’s just great to work with someone like that.” McBean’s sense of swing, the back and forth, and human give and take between multiple dimensions of living, rocks across the pylons and pinions of Ferreira’s electronic edge, the hard surface of an increasingly technological world. That elasticity of purpose — soul — went all the way back to the beginning of time. Athleticism of the mind, The Advent were still wearing their beanies and their tracksuits, their Nike jumpers and sneakers like in the Elements of Life album photograph art — techno-breakdancers air-dropping into New Beginnings…

And so — The Advent also stunned with a host of four-to-the-floor stompers. ‘C. Control’ was a fever of technoid psychedelia, its temperature climbing the complex architectures of an invisible city. ‘House Seed’ banged to a relentless groove, its bass line so hulking, it belonged in a carrier-class shipyard. The critic Tim Barr described tracks like ‘Nervous Energies’ and ‘Stassis (Part II)’ as a “drag-race through distant galaxies.” The same could also be said for the album’s opener, ‘Armageden,’ which accelerated along the outer rings of Saturn, its crunching beats torquing with a syncopative G-force, slipstreaming and overtaking the straighter competition.

Adhering to a more tech-centric palette and highly syncopated rhythms, tracks like the half-time tripper ‘Runners’ and the brooding high-hat prowler ‘Pro II’ throbbed in an endless space of the mind-body connection — unlocking mysteries by the second. The exhilarating ‘Testing’ pulls up alongside everyday perceptions with flashes on the periphery, little galaxies and comets flickering on the window glass of an interstellar spaceship, engines banging to a jockey whip, spinning off into infinity as ‘Standers’ wobbles to alien signals, hypnotizing neural networks into a recon sweep of distant moons. And ‘Insight’ buzzes to the space invasion of insectoid hivers, recolonizing Planet Earth — before ‘Stassis (Part II)’ bumps to its revolutionary and humanoid consciousness, with controls set for the heart of an eternal quantum escape.

The image of The Advent was streetwise. And yet they prowled the streets of computerized fantasies more akin to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner than the later cyborgian derivation of The Matrix. Throughout was the image of a man in some stripped down essence, his underlying mechanics exposed, veined, neural linked, sinewed. In Blade Runner, while an early influence on cyberpunk, humanity is more finding its way through outer space than cyberspace. In that Elements of Life album photo, taken by Vincent MacDonald, Ferreira’s hair is slicked back and McBean is wearing yellow and black camouflaged pants, looking down in midair through the skyscrapers around them as they hover with their sneaker treads, a red negative shadow catching their eyes and faces. They’re ready for the next stage of flight.

As Ferreira noted to Mixmag, they were tough and uncompromising in their long pursuit of techno’s bass, beats and effects. “And when they play live the intensity is breathtaking,” wrote Jones, “machine beats careering wildly into each other, cymbals scything and slashing through the mix, while murky, liquid noises cry out from the depths of sound.” New Beginnings captured that intensity for posterity in all of its glorious power. “It’ll be more militant, more rough,” Ferreira told Jones, explaining pressures that came down on them artistically from Pete Tong, the A&R head of London Records’ dance roster. “We’re not gonna make techno he likes,” he said defiantly, refusing Tong’s mainstream-ism. “We’re still gonna go really head on.”

Their identity was intensity. Not in some belligerent or mindless way, per se, but in wholly mental and intellectual ways — techno as the articulation of a commitment to technological and artistic excellence coming together: New Beginnings was a kind of escape pod. And from their pod, they were drop-shipping into the future. In fact, The Advent had always been on its own kind of trip. “When he was 17 he’d been nicked for spraying trains in Acton Town train depot and had been in and out of court ever since. Finally matters had come to a head and he was sent down for criminal damage,” wrote Jones of Ferreira’s rebellious youth, “spending six days in Brixton prison, two days in Chelmsford and another few in an Ipswich Detention Centre.” And that’s where they buzzed his hair, making him a “less-than-proud” skinhead, when he met McBean.

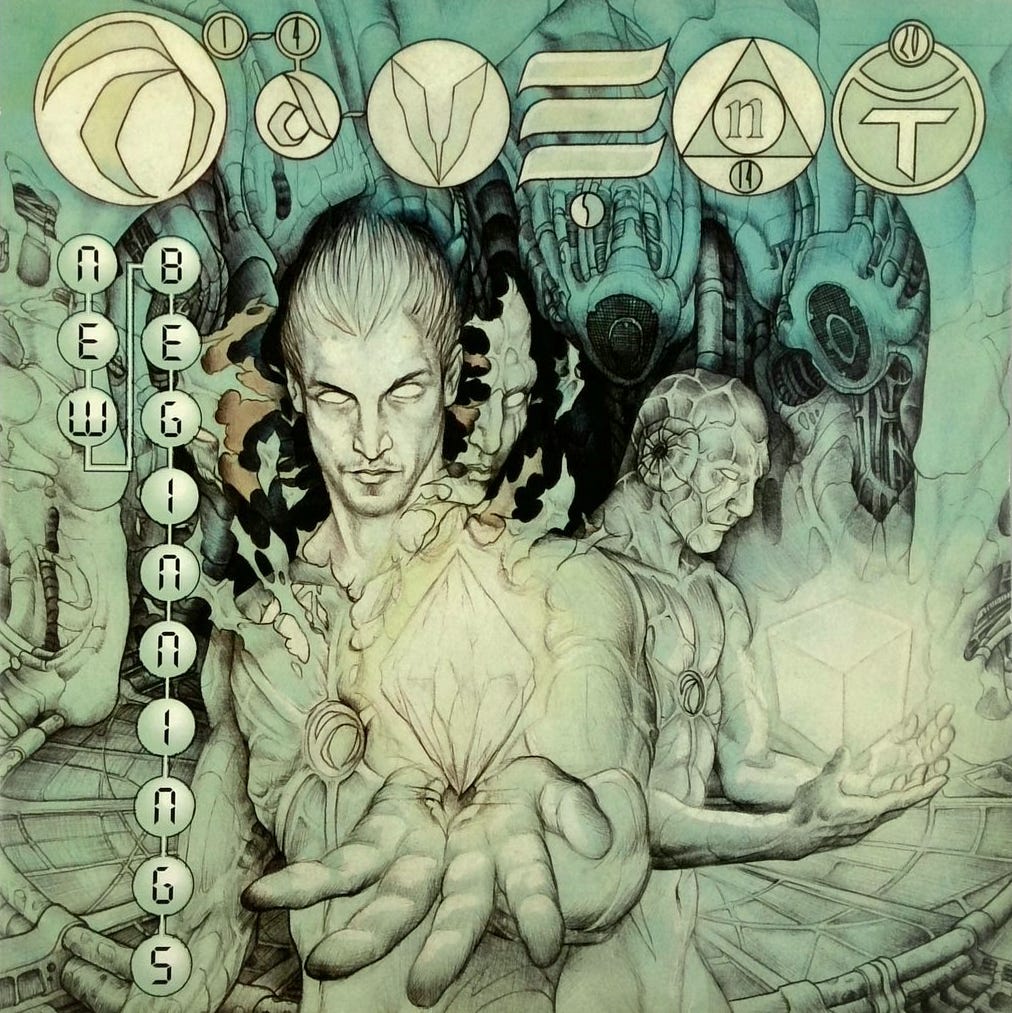

The sci-fi funk theme on New Beginnings was all about liberation then. This was music fit for a space armada, its far-out time traps creaking open wormholes, while charting the hidden order of the universe. The album’s neo-gothic artwork by graffiti illustrator Jason McFee perfectly matched the superstitious vibe, with its sly traces of H.R. Giger’s mystical bio-mechanical aesthetic, depicting Ferreira and McBean waking to cosmic discovery, uncovering new dimensions in a long, cold, hibernating humanity: elements of life reaching a new kind of transformation. Not just through anti-gravity dance moves, but through an uncompromising imagination. Their eyes are bright. Decades on, from start to finish and back, New Beginnings scorches like a fiend.

“Machines and mistakes are what make the magic happen,” noted Ferreira, drawing lines from The Advent’s sci-fi futurism to their highly personal and authentic style. “A turn of a switch can make or break the session or vibe ... stumbling upon unknown sounds and weird sequences that you never tried, then you usually hit the spot ...” Mistakes then reveal the human through a high contrast; the machines must then sound like machines, not some A.I. powered copy of the human; that is, the more inhuman, the more human techno becomes; and as counterintuitive as that may sound, nonetheless, the more intuitive the interaction, the more stark it will be: “Human touch is important to get the most out of any machine — we are the programmers. They serve us and our needs, not the other way round.”

That fearless devotion to the future would inspire The Advent’s next moves — escaping Internal Records, they didn’t miss a beat — releasing a steadier stream of vinyl E.P.’s on their own Kombination Research label. The heavy mind-bend ‘Program Da Futur’ belongs to this intense run, its metallic riffs ricocheting with a killer shadow Doppler effect — marking an innovative peak in modern electro techno. Other trippy electro gems included ‘Wasper,’ ‘Factors,’ ‘Vengeance’ and ‘True Combo’; and their heady remixes of New Order‘s ‘Everything’s Gone Green’ also demanded attention. And a compilation, Kombination Phunk, an expert selection of like-minded artists including tracks and re-edits by The Advent, remains a benchmark of the genre.

Renowned for their banging live shows, Ferreira and McBean had set dance floors ablaze throughout Europe in the 1990s. But in the new millennium, tired of touring, McBean decided to split off and pursue a quieter solo career, releasing the solid Still Here as Mr. G in 2010 — he would cast more tech-house magic with 2012’s excellent State of Flux, and the dynamic Personal Momentz and A Good Place…? Ferreira would also consistently knock out quality, including fantastic albums like Light Years Away and Life Cycles, both modern electro classics, and romping house as G-Flame.***

Electro songs like ‘Mass Media’ and ‘Passage Through The Cozzmozz’ on the Light Years Away album, and ‘Electrical Sounds’ and ‘Boogie Electro’ on Life Cycles, were some of Ferreira’s best compositions in his many years of recording, scratching an itch deep down in the techno soul of the 21st century and beyond — too often marooned by the dizzying chaos that internet technology stirred up. And strolling, grooving, marching, was McBean’s more gritty, warmer, smoother drift, his ‘Dark Heart.....,’ ‘Platonic Solids No.5,’ ‘New Life (E>S>P)’ and ‘Life’s Riddim’ breaking it all down.

“Everybody has a reason and a purpose to do what they aspire to, be it art or not art, spoken word, etc., etc. Since an early age, music was always in my path and always a dream to make it full time,” Ferreira reasoned years later. “To finally do this as my main occupation has been years of hard work. With art you need time to develop your craft; it can be used as a powerful tool if done right, especially in today’s world, where musicians are just as important and powerful as leaders of the world.”

“It’s about hunger,” McBean told Mixmag’s Stephen Worthy in 2020. “I’m a digger. Every Thursday I go to London to buy records, sneakers, art, clothes. At 58, I’m the oldest swinger in town at a club. But I don’t ever want to be like those people above me who are stars, but aren’t at their best. I want to be the guy who’s still a firework … On it. Tight. Dancing, doing, destroying. And that takes work. I have that hunger more than ever.” McBean cried when he left Ferreira but his solo swing has worked.

Two of Europe’s top producers, each pushing his unique perspective, as that photograph suggests, they swung across the sky, from Atlantic islands to England; though apart, the two have tried to remain friends — McBean was the best man at Ferreira’s wedding — but the dramatic power of their multiracial partnership, best heard on New Beginnings, is now absent, and lives on only in their ‘90s music.

Even so, Ferreira carries on The Advent name at his Akoma Workx studio, and continues to ply his craft with vigor. Living again in Portugal, his house by the sea and raising a family, the hard funk maestro was still hurtling wicked bolts of techno magic. While McBean has kept his stride, meteors flashing across the horizon. The techno faithful watching, and London calling, ever does the pendulum swing.

Track Listing:

1. Armageden

2. Runners

3. Funkage

4. Testing

5. House Seed

6. Pro II

7. Stassis

8. Nervous Energies

9. Standers

10. C. Control

11. Insight

12. Stassis (Part II)

*The importance of the West Indian experience and its immigrant impact on British culture cannot be overstated. Known as the “Windrush” generation, the most significant wave came after World War II as the British Empire receded.

Previous Afro-Carribean immigrants came to England before the 1900s, but it was the Windrush generation that shifted English society in a more multicultural direction, along with Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan and Chinese immigrants. Musically, the Windrush wave brought reggae and dub into British cities and towns.

Of course Bob Marley and other early Reggae stars like Peter Tosh had a major influence on British popular music directly from Jamaica. But it was in the immigrant enclaves and then semi-integrations (many of them troubled by racism and pushback against immigrants), that this more soulful and polyrhythmic instinct took hold, eventually influencing everything from British house and techno to jungle and dubstep, with breakbeat and drum ‘n’ bass in between.

For non-Brits, it’s harder to fully appreciate the criticality of this cultural synthesis. But it is of course everywhere you look and listen. There is the UK reggae of Birmingham for example with UB40 and Steel Pulse. There is Ashley Beedle, Grooverider, Fabio, Goldie, 4 Hero, Dillinja, Moody Boyz, Shut Up & Dance, Mad Professor, Jah Shaka, Shara Nelson, Billy Ocean, Culture Club’s Mikey Craig, and The Real Thing.

There is of course the famed Bristol scene, with its trip hop and drum ‘n’ bass roots anchored in reggae and dub as well as hip hop, house, and funk — including Tricky, Roni Size, Krust, Massive Attack’s Daddy G and Mushroom. Then further north was Manchester’s A Guy Called Gerald and Yargo; Sheffield’s Robert Gordon; Leeds’ Neville Staple, Nightmares On Wax, and Martin Williams of LFO fame.

London’s On-U Sound, African Head Charge, Aswad, Maxi Priest, LTJ Bukem, the Thompson Twins’ Joe Leeway and others speak to the multicultural universe of London itself. For example, On-U Sound had a major influence on the likes of Underworld and Leftfield. And even as far north as Scotland, African descent innovators like Keith Robinson formed the Desert Storm acid house group — important purveyors and groundbreakers of techno across Europe.

**Latin freestyle is a less well known genre of electronic music given the bigger shadow of electro and hip hop, but as a branch of the same milieu and given its own set of innovations — as Ferreira points out in terms of its edit style — its importance is still considerable. Hispanic Americans and Italian Americans were also the main proponents of the genre, though not solely.

Originating in New York and then spreading to Philadelphia and Miami, it was a subcultural reaction to Afrika Bambaata & the Soul Sonic Force’s ‘Planet Rock,’ which in turn sampled Kraftwerk. In New York, Shannon’s ‘Let the Music Play,’ produced by Chris Barbosa and Mark Leggitt, used a TR-808 and the TB-303, along with reverb and clever drum programming, to move music into a new “dance pop” era following the backlash against disco. In the studio, engineers and editors, and hence remixers like Omar Santana and Jose “Animal” Diaz also transmuted similar sounds in new ways, their rhythmic edits emphasizing a syncopated and percussive style that brought in subtle Latin influences to hip hop, electro and pop records.

Freestyle also influenced the likes of Todd Terry, Man Parrish and the production team of Tommy Musto and Frankie Bones, who worked with freestyle artists early on and in turn produced intense rhythm and breaks edits that would make their way to the UK, in turn influencing DJs like Carl Cox, Grooverider and Fabio. In Miami, there was also of course the emergence of the Miami Bass sound, much of it driven early on by pioneers like the Black electro team, Free Style.

One other critical cross-point of these electronic and rhythmic chain reactions was Jellybean Benitez, who started his DJ residency at the famed Funhouse in New York City. It was there that he played electro and freestyle heavily, helping break ‘Planet Rock’ and ‘Let the Music Play.’ The Funhouse is also where younger cohorts like Santana and Bones first took their lead. Obviously, Ferreira was paying attention.

***For fans of The Advent, it can help to understand why two of your favorite artists decide to part ways. While it is my understanding that both Ferreira and McBean are still pals, they did finally come to a fork in the road around 2000. Ultimately, Ferreira felt like he was doing most of the studio work, putting in long, intensely focused hours. And McBean also felt constrained, because he didn’t have the full studio exposure that Ferreira had, and that he desired to grow as an artist. In 2016, he described it to Skiddle’s Thorp this way:

“Well, Cisco and I had our differences. He was more the studio man, where as I’d bring the samples and the ideas. But towards the end, I wanted something more. And I had to take something to get started. So I thought, yeah, I’ve worked on the MPC, and then spent two years locked away in a box learning the machine. And I still probably don’t use it like anyone else in the world.”

For his part, Ferreira described it similarly, in that their parting was mutual and essentially natural, though there is obviously a difference between the McBean era of The Advent and the post McBean era. Both are excellent solo artists, but there was certainly a great mixture of influences and instincts as The Advent duo. Ferreira:

“It was complicated in the end as it always is but also frustrating from my side, as I was putting in all the studio work. I guess it just felt like our time was coming to an end. I had other ideas I wanted to try out and other artists I wanted to collab with. So, I decided to carry on the Advent solo but helped him set up his label and taught him some tricks on the Akai MPC2000 to get that G Sound.”