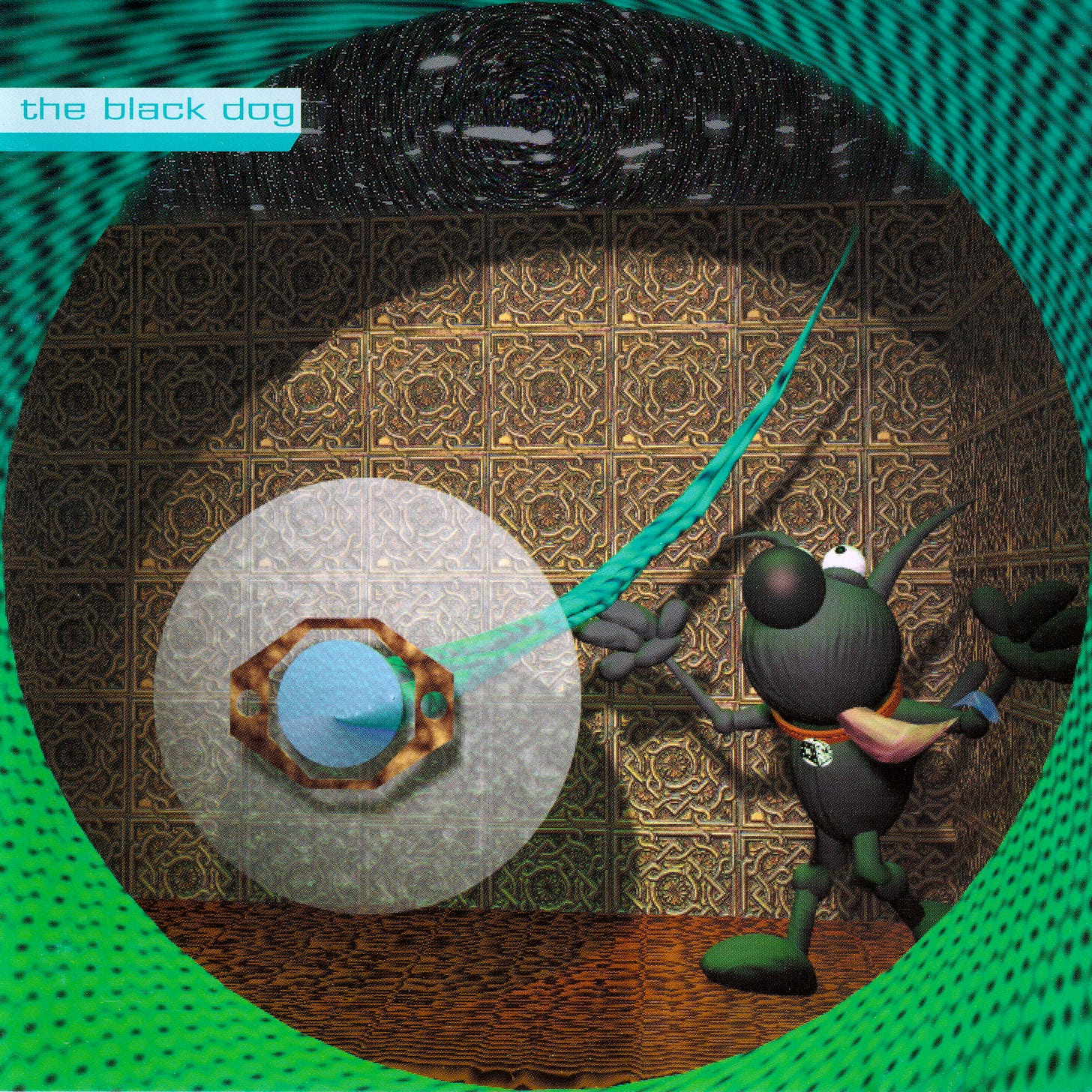

The Black Dog - ’Temple of Transparent Walls’

No. 31 of our Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s

The Black Dog was one of the first “intelligent dance music” outfits to carry the Warp Records banner. Celebrated in the press and adored by Björk, The Black Dog was a three-man effort: Ken Downie, an ex-naval radio operator, and b-boys Andy Turner and Ed Handley, who later formed Plaid on their own. The three released several groundbreaking E.P.’s in 1989 and 1990 — Virtual, Age of Slack and Playtime — including Plaid’s gem album Mbuki Mvuki in 1991, and Black Dog’s first General Production Recordings output, all later collected on 1995’s Parallel, Warp’s retrospective Trainer in 2000, and 2007’s Book of Dogma.

In 1993, the trio released two of their best long-plays together, Bytes on Warp, and Temple of Transparent Walls on GPR.* The second, which is their weirder effort, took more chances and is more cohesive.** Recorded at Techno Island Studio, the sonic forge of R&S Records, during an extended stay in Ghent, Belgium, Temple is filled with tinker toy melodies and drunken electronics, at times astray in a sad metropolis or jumping for joy in a sonic junkyard of the future. At its heart is an indomitable sense of adventure, of taking chances and dreaming even bigger.

Always playing with concepts and names, like breakdancers breaking ideas on the dance floor of the 1990s computer matrix, they aptly named this mysterious epic in the vein of oracles and ancient divinations. The idea of “transparent walls” evokes the invisible cities that emerged out of the Internet, what the cyberpunk author William Gibson once described in his novel Neuromancer as “clusters and constellations of data….Like city lights, receding…” i.e. cyberspace. That the name of the album was unfortunately released as “Temple of Transparent Balls” is a beguiling and poetic reminder of the technological glitches and ghosts in the machine — the human.

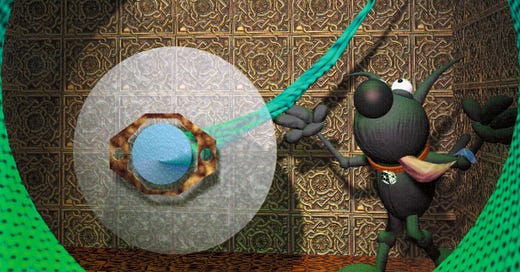

Its cover art a quintessential artifact of ‘90s computer graphics, it shows a “black dog” in some kind of ornate techno-temple structure, a pendulum or transparent ball swinging, looking up at swirls of data or stars, hard to make out, but still reflecting the mesmerizing power of the electronic and the infinite all at once. This half-serious and almost cartoony take on the classical “music of the spheres,” presents us with a clever tone that permeates throughout The Black Dog’s Temple: the Sun, Moon, planets and their orbits form a kind of meta-clock — a mysterium for the soul.

“When we were Black Dog, we used to host a lot of websites and things to do with those kind of Egyptian cults,” Handley told Red Bull Music Academy in 2003. “It was just the association and it was sort of the early days of the Internet, where it was built-in board systems, and we used to host the Pagan Federation site as well…I think it was escaping from fairly dull jobs…Andy was a shipping clerk and Ken was a caretaker. So we all had these jobs that weren’t that fulfilling. They were really just to pay the rent. So certainly, at that point the music was to express some desire for freedom and to escape that Monday in your life.”

Restless to the max and one of the first UK techno acts to embrace a darker hacker ethos, appearing in early press photos as shadowy hooded figures, The Black Dog embraced the weird — from the LSD-inspired cartoons of Robert Crumb to the old concept of the devilish black dog of British folklore — and the philosophical — the hallucinatory visions of a virtual reality society and the late-night musings of early Internet relay chats, a rave new world connected and dreaming. While their own independent label Black Dog Productions released their first three E.P.’s — first introducing astonishing, head-spinning epics like ‘Virtual’ as early as 1989 and cathedrals of electronic prophecy like ‘Techno Playtime’ in 1990 — by 1991, a spiritualist sound emerged with ‘VIR2L,’ a manic reggae-breakdance beauty.

While their GPR phase yielded three more towering E.P.’s — featuring the deep hypnotism of ‘Hub,’ the urgent empathy of ‘Glossolalia’ and the pleading chirps of ‘Vanttool’ — The Black Dog were already searching for more artistic outlets, landing a deal with Rising High Records in parallel. In 1993, they released a new E.P., this time as Black Dog Productions, including the classic ‘Otaku’ and ‘Flux,’ both long, winding and surfing travelogues into the furthest reaches of European techno’s romantic drift. The heartache yet optimistic tone of the two songs, one done by Turner as Atypic and the other by Handley as Balil, expressed both their frustrations with the music business and their youthful sense of a limitless future: nothing was going to stop them. More volatile than fixed, The Black Dog was in truth a story of great boundless ambition.

“So where are these invisible entities? Atypic, Balil, Plaid, Echo Mix, Discordian Popes, Xeper, IAO?” wrote David Toop for Mixmag in April 1993, listing The Black Dog’s many aliases, and describing their London digs. “Physically, they are sitting in a row in Black Dog Towers, a terraced house in Mile End, a small room lined with computer monitors and low grade recording gear, keyboards perched on available surfaces,” he wrote, teasing out the mundane, next to the extraordinary and telling: “a wardrobe in one corner, the sound of fan-cooling and messages coming through on the computer bulletin board.” At the time, they were only reachable by modem. “A copy of Ian McEwan’s novel, Black Dogs, sits above the dusty mining desk,” he discovered.

Inside that temple whirled a storm of ideas — the black dog is a symbol of luck, emerging in Downie’s mind when he was in Denmark in 1984: “There was a dream, a sort of weirdness, several coincidences,” he told Toop, who also drew parallels with Winston Churchill’s name for his recurrent depression — his “black dog.” Whatever inspiration it represented, The Black Dog sound spoke for itself. It was weird. But incessantly funky too. “Fun not money” was the advert copy Downie put into the classified pages of a July 1989 issue of Music Technology. Turner and Handley answered. Downie had engineered for punk bands — meeting The KLF’s merry prankster Jimmy Cauty, he realized he could apply his computer skills to the production of music. Turner was a hip hop DJ. Handley crafted breakbeats.

It was that melding yet clashing of hip hop and house, techno and punk, that generated The Black Dog dynamic. Handley and Turner were younger than Downie and obsessed with breakdancing. Handley was a popper and locker. Turner was a windmiller. They studied flares and freezes and fusion moves. Their energy would bring a more unpredictable yet graceful aesthetic to the mix. Downie on the other hand was more about big ideas and sweeps, his time in the Royal Navy coloring a more expansive view on music and its history, taking in waves past, present, and future. His ‘Carceres Ex Novum,’ as Xeper, is a loving trip into deeper currents of human emotion, at once torn and tranquil. His swoosh-y ‘Fight the Hits’ jazz, as Discordian Popes, trips even harder. But the other two dogs were more prolific.

A ‘Whirling of Spirits,’ ‘Scoobs In Columbia,’ ‘Bouncing Checks,’ ‘Angry Dolphin,’ ‘Uneasy Listening,’ ‘Norte Route,’ ‘Parasight,’ ‘Island’ — music was spilling out of the ears of Turner and Handley as they leaned into their Plaid identity. Bytes exhibited in many ways an uneasy threesome. More a collection of songs than an actual album, it nonetheless ranks perhaps highest as a fan favorite. It features the scaling heights of ‘Object Orient,’ the levitating glide of ‘Olivine,’ the lunar grooves of ‘The Clan,’ the fairy dance of ‘Merck,’ the wending ways of ‘Focus Mel,’ and the vamping joy of ‘3/4 Heart’ closing it out. Even so, their invisible identities shimmered as one for Temple.

For the three dogs refracted that mental confinement into a kind of game of obscuration, their music like the glimmering surface of a deeper proposition: The Black Dog were an odd complex of worldviews, fusing ‘bleep’ techno with dub, jazz, ambient and hip hop sensibilities — Temple compressed those influences into a sonic gemstone. “From the opening digital skank of ‘Cost I’ to the closing circuit board tears on ‘The Crete That Crete Made,’” wrote critic Peter McIntyre, proclaiming that it was a singular and innovative classic, and “took every single strand of modern music, mixed it all up and produced something that sounded like nothing else on the planet.”

“The Black Dog can only speculate on the possibilities of creating an interactive, computer-generated artificial world through which listeners can move, fantasize, alter the sounds they are hearing, losing their familiar sense of self,” wrote Toop. “How they foresee the visual style of this world or the altered state in which the participant negotiates virtuality differs sharply between the three of them.” In a small room, confined. In a temple, devoted. In a virtual world, freed. The trick? Transparent.

“Ancient, something classical,” is how Downie described his own idiosyncratic vision for virtual reality to Toop, the Brian Eno-blessed ambient traveler and wonderer. “I’ve always been interested in history and it would be nice to start off with that rather than high technology, cubes and science fiction.” And so, his Temple wound the clock back in time to the primordial beginnings of the Western mind. Handley was at the opposite pole of virtuality, as Toop observed. “I’d like to create an abstract virtual reality,” he averred. “Obviously, there’s no point in having a computer generated environment unless you can do things that you can’t do in reality.”

And then there was Turner, who could bring both visions into a kind of stereoscopic focus. “Andy looks forward to virtual identity and the prospects of putting himself into another species,” wrote Toop, perceiving Turner’s vision of humanity’s transformation through the transparent walls of the techno temple. “So, imagine yourself in five years time, experiencing a Black Dog production in your new, temporary (you hope) identity as a bat, perhaps hanging upside down in a Medieval monastery, changing the decay time of the echoes every time you flap your wings.”

Of course, it wouldn’t take five years, because by September 1993, “Temple of Transparent Balls” was out in the world. GPR was struggling, so fewer critics and fans would ever hear it, for these were the days before the retail Internet. In a way, it was almost a kind of techno Dark Castle, the 1986 video game popularized on the first Apple Macintosh, but elusive too for it was mostly inaccessible to the masses — a flapping bat flying through its doors and over its walls. The point was not just a computer generated environment beyond reality, but reimagining humanity. To reimagine the human species, you would need to go back into our mythology.

‘Cost I’ was the perfect entrance to the mystic yet secret in its approach — the gentlest swing and skank of its dub walk, passing on through the gorgeous cross-currents of The Black Dog’s synth wafts — the quest unlocked. Tracks like ‘4, 7, 8’ and ‘Sharp Shooting on Saturn’ swayed like marionettes to delirious melodies, the arrows of Apollo and Artemis hitting their mark, the god Cronos teaching the peaceful arts. ‘Jupiler’ revs up like a possessed motor, a bumper car ride through an eye-popping bubble city. ‘The Actor and Audience’ frets and soothes with its electronic chorus, evoking the tragedies of Oedipus and Elektra, and the comedies of Aristophanes, perhaps The Frogs with its side-commentary on Dionysus, or the myths of the Argonauts and the thousand ships that set sail for Troy to appease Menelaus.

The message? Such mistakes and heroics of the human past would repeat in tomorrow’s matrix. ‘Cycle’ rams about to the warp of marching machines, provoking Handley’s interest in the abstract and the superhuman. ‘Mango’ follows a similar line, this time freaking to Latin rhythms and ragtime keys, a frenetic jam session in a video game jungle. Or serious numbers like the bolo-strut of ‘Cost II,’ the soul-searching of ‘Kings of Sparta,’ and the ethereal homecoming of ‘In the Light of the Grey,’ the bats gliding through caves and out into sun rays, are both moody and quirky, while ‘The Crete That Crete Made’ is a lullaby for robots. ‘Cost I,’ ‘Cost II,’ ‘Sharp Shooting on Saturn’ and ‘The Crete That Crete Made’ still stand out as wonders of a lost world emerging in the future through the medium of emotions, all stronger than before.

‘Cost II’ and ‘The Crete That Crete Made’ alone make Temple of Transparent Walls The Black Dog’s greatest achievement, anchoring the album in a great expanse of emotion. The former floats us out over what feels like a great computer generated grid, at once a kind of outer space and inner world. Oxygen piping in, life really does sound more magical in your head walking on the Moon. And ‘The Crete That Crete Made’ gently rocks in the sea, the seagulls flying overhead, the many voyages of ancient peoples running through our souls from our past to our future — its little melodic glimmers evoke The Cure’s Disintegration from Egypt to Crete to Belgium and London.***

“I was naïve, trusting, optimistic, and foolish,” Downie reminisced about the halcyon days of The Black Dog to blogger Jonty Skrufff in 2007, after resurrecting his career in the 2000s. “I genuinely thought we were a ‘rock and roll’ band, in the tradition of the Sex Pistols, Clash, Damned, etc. Us against the world. Looking back, it was the best way to be, because I had a genuinely excellent time.” And in a real way, it is that fun innocence that makes Temples such a quiet triumph. It may sound rough to more digitized ears, but its analog warmth, its playfulness, its heart on its sleeves, its electronic patina, is what makes it an indispensable document, a roadmap to happiness, as if it were a codex full of dreams from the first rave civilization.

Here we had a trip through the ages, but one in the spirit of astronomers and astrologers going back to the ancients: Pythagorean coordinates, interplanetary rhythms, the Minotaur and the Maze in Crete, a Dionysian theater and the wars of Sparta, the metaphysical map outside of temporal walls. That Downie, Turner and Handley took that heritage of the West, remapped it to the North, South and East, is a testament to their sly inner compass, the genius cruise of ‘Cost II,’ the space station blues of its adieu, ricocheting us back to the future and far out into the Odyssean unknown of Homer’s “wine-dark” cyber seas, the stars forever spiraling over us.

“The idea of modulating a sound throughout five minutes is a pretty strange idea — adjusting the filter so that no one point of the song is exactly the same,” Handley told Toop about his own acid house rave revelation. “That was a fairly strange concept for music.” And you can hear it across Temple, but twisted and turned and rethought too, angles and facets and lines of the transformative and transparent. As Toop noted of 1991, after The Black Dog had put out its first three groundbreaking E.P.’s, that “the combination of Chicago acid, Detroit techno, acid parties, media hype, pirate radio and the easy access technology…cheap and versatile sequencing software, more powerful sampling capacity…opened a large box out of which flew a swarm of cyberian experimentalists.” Or a swarm of bats, depending how you look at it.

Back in that Black Dog Tower in Mile End, in East London, in that small room, the Temple of Transparent Walls, Toop distilled down the shift that the three bats or dogs or cyberian experimentalists exemplified at its best. “Nobody here is wearing Star Trek gear or carrying a pilot’s license. This is travel in the non-corporeal information age,” he wrote, “ideas exchanged in the electronic well, string sections by the click of a mouse, remixes transferred over telephone lines, deals concluded with a digital handshake.” That may sound mundane today, but it was and still is, real magic; echolocation of the heart and the spirit the eternal question of any great artist.

And inside that novel above the dusty miner’s desk, were echoes of the light and the dark of this real magic. “In the silence of that corridor, between the two phases of the planned entertainment, I glimpsed what adulthood, the real thing, was really about: it was about having the strength to confront in the lives of others those moments of unreason, those edges or swamps of dissolution, which most frightened us in ourselves,” wrote McEwan. So mirrors too then amid the transparently human; nevertheless, Black Dogs, a story about moral confusion perhaps speaks to a profound alienation, but not to their great leap into the temple of imagination.

Walking in those corridors, dreaming in their tower, rewiring myths in the machine,

The Black Dog was always mercurial in its experiments, an upside down world of zero gravity techno fantasies. Later productions would prove consistently powerful in their delicateness. Spanners is their other great monument to this heady optimistic era of reflective dance music. But in terms of its glee and sense of discovery, nothing The Black Dog gang did before or after, together or apart, quite matches the feverish games inside the Temple of Transparent Walls. Step on in, and find yourself breakdancing in an astronaut’s dream.

Track Listing:

1. Cost I

2. Cost II

3. 4, 7, 8

4. The Actor and Audience

5. Jupiler

6. Kings of Sparta

7. Sharp Shooting on Saturn

8. Mango

9. Cycle

10. In the Light of Grey

11. The Crete That Crete Made

*I have taken a little liberty with titling this historic release as Temple of Transparent Walls instead of Balls. There are different stories about why GPR released the album with the Balls title. The master tape was titled with Walls, but apparently a legal and A&R dispute led to a falling out between GPR and The Black Dog camp. Downie, Turner and Handley in fact switched to Warp Records the same year, and had to release their first album as “Black Dog Productions” due to the wrangle.

The Balls title is what will come up on searches and in Discogs. But, I decided to dispense with the slightly humorous “Balls” in the spirit that “Walls” was in fact the artists’ original intent, and because the Walls title hits a more even tone in terms of the album’s thematic ambitions — a sonic exploration of the classical and digital, the ancient and the futuristic, the electronic and the galactic, i.e. a spiritual matrix.

And while a remastered blessed version was released in 2007 by Soma Quality Recordings — the same glitched title of Balls still in place — even so, returning the album to its original title hopefully gives newcomers and longtime fans a fresh perspective on this winning and elusive artifact.

**Many may disagree with the assessment that Temple of Transparent Walls is superior to Bytes. The latter is in no way a slack effort. It is in many ways better than Temple, especially in a more “Detroit techno” sense, including brilliant compositions like ‘Olivine,’ ‘Merck,’ ‘3/4 Heart’ and ‘Focus Mel.’ However, it is less concentrated and is importantly a compilation versus an album, though it was released as such for legal reasons under the “Black Dog Productions” banner and because it was expedited as part of Warp’s Artificial Intelligence album series. It’s name, “Bytes,” a pun on Black Dog “bites,” indicates its more piecemeal nature, along with its ‘Phil’ fills.

Therefore, for these reasons, Temple just slightly surpasses Bytes in a retrospective sense to my ears because of its cohesion and its singular arc. And because Bytes is ultimately a compilation and its tracks are written and are additionally credited to separate aliases (with the exception of two by Plaid), I have also decided to not include Bytes as its own Top 100 entry due to this critical difference.

Nonetheless, out of respect for Bytes and in recognition of the music industry disruptions The Black Dog endured, I hope to at some point include an entry and tribute to Bytes, and as a salutation to its many fans.

***Other than the album’s official name being a misnomer, one other blemish resulting from the GPR mismanagement of The Black Dog, is the bass line distortion in the right channel during beginning measures of ‘Cost II,’ which likely stemmed from a poor final mastering of the album, marring the ideal with abrasions of the real.

‘Cost II’ was initially released on vinyl as a single, where the song can be heard without the distortion. Even the reissues by Soma retained the flaw. As with many treasures of the world, a true ‘Temple of Transparent Walls’ is forever elusive. Yet like some dusty mixtape, for the curious and committed, its power cannot be restrained.

Also, the track ‘Jupiler’ may seem like a typo like the album title. There is a cosmic theme and aesthetic to the album à la ‘Sharp Shooting on Saturn.’ But this is actually likely a little wink and joke as Jupiler is the name of the highest selling beer in Belgium, helping give Temple a vibe of camaraderie, location and history.