The Chemical Brothers - ’Exit Planet Dust’

No. 32 in our Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s

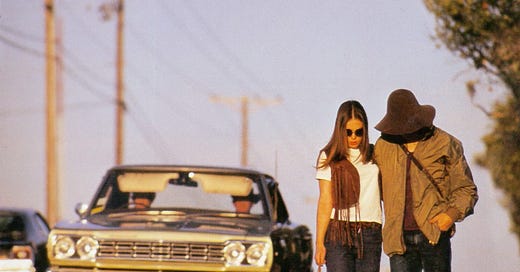

Exit Planet Dust was the beginning of an unlikely journey. The Chemical Brothers‘ earliest fans originally mistook the English duo, who looked more like they were from Milwaukee or the stoner dens of California than hip London, for the Los Angeles-based producers The Dust Brothers. Ed Simons and Tom Rowlands had originally used “The Dust Brothers” moniker as a tribute to their LA-based heroes, the American duo John King and Mike Simpson who produced the seminal Beastie Boys album, 1989’s Paul’s Boutique. They switched their name when the real deal threatened to sue.

But Simons and Rowlands didn’t need the allusion as their early singles exploded on dance floors across the globe with incredible force, making them the talk of the rave world overnight. ‘Song to the Siren’ was their first breakthrough, a poundcake of Run DMC-inspired beats and heady acid tweaks: “Born in Tom’s bedroom on a hitachi hi-fi, a computer, a S1000 sampler and one keyboard with no effects,” wrote the journalist Andy Pemberton, “….As well as a grounding in mid-80s hip hop, the work of producer Marley Marl and acts like Schooly D and Public Enemy, ‘Song to the Siren,’ a hip hop stompathon with sirens and spooky ambience to go, was a terrifying noisefest that sampled the This Mortal Coil track of the same name.”

Picked up and signed to Junior Boy’s Own by none other than acid house journeyman Andy Weatherall, it detonated in London clubland with shockwaves that rocketed their career forward. But it was ‘Chemical Beats’ that tore the roof off. It was a reach-for-the sky blast of scratching acid squiggles, pinpoint cow bells and stadium-gaping crowd dynamics, tossing everyone over the Moon. “I like all types of music, that’s what it’s about,” Rowlands told Pemberton. “There’s no division.” And in that — the boom.

It is sometimes easy to forget how central breakbeats and the legacy of funk was to the innovation and rise of rave music. It was not all just about New York post-disco, Chicago house and Detroit techno. In addition to the absorption of reggae and dub music via Britain’s West Indian cultural byways, the heady ethereal grooves of Italo-disco à la Giorgio Moroder, and the influence of Kraftwerk on Brian Eno and David Bowie birthing post-punk and new wave, the impact of hip hop on a generation of music-makers cannot be underestimated, especially in the UK.

And lest we forget, so too did polyrhythm emanate from rock with blues, jazz and country scintillating with their drums and percussive guitar picks; as did it ripple from the “world music” that the likes of Peter Gabriel, Herbie Hancock and African Head Charge championed and transmuted. All of this exploded with a dynamic force, the echoes shattering across time and space despite the indifference of the masses, ricocheting through the Chemical Brothers’ synths and samplers, a sort of drum-consciousness that spoke far beyond London and across the Atlantic.

From the breakthroughs of Shut Up & Dance, the proto-jungle of A Guy Called Gerald, the intense slamming hardcore syncopations of the likes of 2 Bad Mice (‘Bombscare’), The Prodigy (‘What Evil Lurks’), Future Sound of London (‘Tingler’ as Smart Systems), LFO (‘LFO’), Renegade Soundwave ('The Phantom’) and Eon (‘Spice’), including back to Juan Atkins’ early Cybotron (‘Clear’) and his Model 500 hybrids (‘No UFO’s’ and ‘Sound of Stereo’), and Frankie Bones’ Bonesbreaks series (‘Janet’s Revenge’) and Florida and West Coast stepchildren (DJ Icee and Exist Dance), the trans-Atlantic breakbeat sound clash was alive and real and even hyper-real — the hardcore.

Shared between the Old World and the New World was this love of rhythm, the backbeat and the breakbeat, the soul strut and harrumphs of James Brown and the J.B.’s, Sly & The Family Stone, Parliament/Funkadelic, on through to Michael Jackson and the Brothers Johnson, War and Mandrill, The Last Poets and Stevie Wonder, and Tonto’s Expanding Head Band. All that bedrock inspiring DJ Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash, Kurtis Blow, and eventually the Def Jam crew, De La Soul, The Jungle Brothers and A Tribe Called Quest. It was ping pong in a storm of the electron. The Chemical Brothers took all that lightning and sent it through the acid house matrix.

‘Chemical Beats’ was like hearing this static vortex crackling high in the clouds. You could hear it descending from the sky from London all the way to America’s West Coast, a propeller plane zapped and howling as it sped to its target. Bombs away. Landing on the El Mirage dry lakebed in the Mojave Desert at California’s famous Moontribe parties, it was like a mushroom cloud going off in people’s heads. It throttled any DJ set into a pulse wave so elastic, the mountains and the hills disappeared in a flash. Walls and skyscrapers vanished. An ode to bass.

An ode that many heard and returned. Running in parallel was the progressive breakbeat house of Leftfield and on some occasions, Orbital, who borrowed some of the breaks from Meat Beat Manifesto’s ‘Mindstream’ on the banging ‘Remind’ by way of soul-funk drummer Bernard Purdie. More trance-like styles used breaks heavily as well, including on Hardfloor’s exhilarating ‘Acperience 1,’ Underworld’s ‘Born Slippy’ and ‘Cowgirl,’ Empirion’s hedonistic ‘Narcotic Influence 2,’ and Josh Wink’s helter-skelter ‘Higher State of Consciousness.’ In the wake of ‘Chemical Beats’ came a focussed breaks movement in the form of Fat Boy Slim, Bentley Rhythm Ace, Propellerheads, Death In Vegas, Rennie Pilgrem and Monkey Mafia.

The respective “Big Beat Boutique” Skint, Concrete, Thursday Club Recordings and Wall of Sound crews in the UK are just a small sampling of breaks acts that ‘Chemical Beats’ helped crystallize. While Weatherall had already brought a rock-drum vibe to UK dance culture, it took the Chemical Brothers to bring all of the disparate strains together. As UK hardcore pushed in dizzying directions evolving into drum ‘n’ bass from templates set in part by New York’s hardscrabble techno template, from the Bonesbreaks records produced by Frankie Bones to the break-y stomp of Joey Beltram’s ‘Energy Flash,’ the Chemicals kept it in acid house tempo and spirit.

What was so evident from the start was their knack for concocting rocking beats that they then dashed against the precision of techno. The meticulous placement of a tiny softer bass pulse right after the big drum on ‘Chemical Beats’ is a prime example — the resulting call-and-response between the main bass drop and the subtler higher note creates a deeper space. It’s a dimensional nudge that tucks you right into the pocket of the groove, like a little angel or devil whispering on your shoulder. Such exacting artistry created a deeper conversation between mind, body and spirit.

Around the same time, the Chemicals were giving the “Dust” treatment to a number of artists, each one a nervy dance floor excursion. Remixes for St. Etienne, Sandals, and Lionrock pushed breakbeat into astonishing new directions. Taking St. Etienne’s ‘Like A Motorway’ and Sandals’ ‘Feet,’ they stretched screeches and screams into spells of anarchy, somewhere between an 8-bit video game and a rock-slide down mystical mountainsides; whirling bolos and beep-beep trucks vying for the first prize in a raucous pinball rally, like Mr. and Mrs. Pac-Man chomping at Armageddon.

Lionrock’s ‘Packet of Peace’ took these wild instincts and pummeled dancers into full-on freakout mode, its chants of “Mister DJ!” battling it out with the robotic “Sound System!” — the floor dropping out at 2:30 before blasting everyone to outer space with a bass kick so thumpy, it feels like you’re on a trampoline bending down to the belly of the planet. Two other remixes would bookend this phase of underground wizardry — reimaginings of Sabres of Paradise’s ‘Tow Truck’ and Manic Street Preachers’ ‘Faster’ — both twisting techno into shattering brilliance.

So the pressure was on when they signed to Virgin Records, not just to keep up the pace and the energy, but to show everyone they made more than heady gutsy breaks. Tapping into this sophisticated but raw hectic energy, Exit Planet Dust punched the accelerator. Its starter ‘Leave Home’ zooms and howls — hooking listeners with its motor funk; ‘In Dust We Trust’ continues the rock guitar grinds, chunky kick drums adding bravado to the psychedelic romp; ‘Song to the Siren’ and ‘Chemical Beats’ make devastating cameos while ‘Three Little Birdies Down Beats’ charged hard, wielding an axe of acid glory, slashing and hacking its way into the groove-land.

But the Chemicals also had a sweet side. The instrumental shimmers of ‘Chico’s Groove’ and the dawn chorus of ‘One Too Many Mornings’ use haunting chords and uplifting rhythms to cast spells of catharsis; while the defiant ‘Life Is Sweet’ features vocals by Tim Burgess of The Charlatans to excellent effect, the first of many rock collaborations on later singles and albums that would include the likes of Noel Gallagher, Wayne Coyne and Richard Ashcroft; and ‘Alive Alone’ reveals a folk songwriting bent, featuring vocalist Beth Orton, who would appear again on subsequent albums, along with Mazzy Star and The Magic Numbers.

But ‘One Too Many Mornings’ is the sunrise that shines brightest over Planet Dust. Taking samples from Swallow’s 1992 “shoegaze” album Blowback, the songs ‘Follow Me Down’ and ‘Peekaboo,’ its hand drums and Louise Trehy’s high vocal lilt, mixed with breaks sampled from Dexter Wansel’s ‘Theme from the Planets,’ Tom and Ed expertly layered in their own deep bass riffs and echoing drums. It’s the way that ‘Mornings’ launches into its groove and its dream symphony, sending the arms and shoulders spinning and hips and knees bobbing, that puts smiles on faces and springs in the steps of feet, and then arcs and surrounds, lifting eyes up to encounter the future horizon. It’s the strongest medicine on the planet — not just ecstasy, but hope.

And yet this more sensitive side had always been a part of the Chemicals blueprint. The Fourteenth Century Sky E.P. — which included ‘One Too Many Mornings’ — also turned the sky into fire with ‘Her Jazz,’ a symphony of deep beats, wicked drum hits and rising devotional vocals and synths worthy of full moon worship. And the early beauty ‘My Mercury Mouth’ floated to a deep dub groove sprinkled with the spry euphoric melodies of Manchester in the spirit of New Order. As Dust so clearly demonstrated, and that Pemberton captured in his Mixmag article — including descriptions of a drug dealer named Satan and a live show encore where the Chemicals took bombastic ‘Chemical Beats’ and mixed it under The Beatles’ ‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’ their music gloried in dazzling contradictions.*

Having first met in a history class over Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales at university in Manchester, then spending their nights at the acid house mecca of The Haçienda and starting their own roaming event, Naked Under Leather, Rowlands and Simons had never looked back, taking the strains of Factory Records, New Order, 808 State, and the infamous DJs Graeme Park and Mike Pickering, to London and into the breakbeat hinterlands. Deconstructing and then recombining their influences into the propulsive and nostalgic gave their sound just the right balance of kinetic oomph and introspective unpredictability: “That’s how we see music,” Simons reflected, wielding records like a knight wields a morning star. “As one big psychedelic bubble. Dance records that fuck with your head.” That’s the trick — a spiked chemical reaction.

In California, simultaneously, the roots of rock and funk and soul and hip hop bubbled in the tar under its heaping vinyl landscape. The Exist Dance stable in LA, where the original Dust Brothers hailed and worked with the Beastie Boys on Paul’s Boutique in 1989, authored ‘Champion Sound’ and trip hop masterpieces like ‘Mya Yadana,’ and released Freaky Chakra’s cult classic, ‘Transcendental Funk Bump.’ Allied with the Hardkiss Brothers, who attracted attention overseas with God Within’s ‘Raincry,’ influenced by FSOL’s ‘Papua New Guinea,’ they prefigured the breakbeat wave. Dubtribe Sound System’s ‘Mother Earth’ and Rabbit in the Moon’s ‘Out of Body Experience’ had helped set the ground two years before Dust, in 1993.**

That was the year that preceded ‘Chemical Beats.’ DJ Icey (or Icee) in Florida was on the same tip, channeling the legacy of Miami Bass, with his Zone Records and Energy Traxx Volume 1, as was LA’s Bassbin Twins, a hip hop aficionado who would relocate to Belgium and then San Francisco in 1994 and carry on the breakbeat flag decades into the future. DJ Dan (Daniel Wherrett), handpicked by Carl Cox as one of his two F.A.C.T. tour co-pilots, would help lead that charge. His West Coast sound is best captured on his Loose Caboose release with Jim Hopkins as Electroliners, and on his mixed CD of the same name; LA DJ’s like Simply Jeff, Jesse Brooks, Fester, Mojo and Moontribe’s John Kelley, whose Funky Desert Breaks would help capture America’s underground zeitgeist in 1995, were part of something much bigger than one band.***

The British music press labeled this psychedelic breakbeat sound as “Big Beat” — easily the most silly name possible for a groundbreaking movement. But in America, few producers and DJs cared about the semantics of genre, and immediately heard kindred spirits in the Chemicals. A psychedelic Pacific wave was moving in California, where producers like Hardkiss, Electroliners, Bassbin Twins, Uberzone, Simon “Two Crates” and The Crystal Method, were extending the canvas in cities, beaches and deserts. Florida was right alongside with DJ Icey and Rabbit in the Moon.

Given the Chemicals’ impressive career, that enthusiasm was right on the mark. There would be plenty of fireworks in the years to come, from growling ‘It Began in Afrika’ to upright anthem ‘Galvanize.’ But Dust threw down the gauntlet: “No one did breakbeat techno like Tom and Ed.” Its rush of electric riffs and explosive rhythms can still get any party jumping, leaving prim heads in a cloud of sonic dust, or carrying the eyes gazing at moonlight into the sunlight, under the hills and over the top.

Track Listing:

1. Leave Home

2. In Dust We Trust

3. Song to the Siren

4. Three Little Birdies Down Beats

5. Fuck Up Beats

6. Chemical Beats

7. Chico’s Groove

8. One Two Many Mornings

9. Life Is Sweet

10. Playground to a Wedgeless Firm

11. Alive Alone

*Not to distract from the main thrust, Pemberton’s article for Mixmag in December 1995, which partially documents The Chemical Brothers’ first tour of North America, hints at some of the usual rock and rave antics backstage. It describes scenes in Chicago and New York, and a dodgy drug dealer who goes by the name Satan.

Overall, the article depicts how quickly and smartly Rowlands and Simons helped form an eclectic mini-subculture around London’s Heavenly Social nightclub, that included the likes of Primal Scream’s Bobbie Gillespie, The Jam’s Paul Weller, and even trip hop god Tricky, and how that fusion of rock, hip hop and techno caught on in America.

**There are so many cross-ways and chain reactions in the early ‘90s, and the breakbeat explosion is perhaps the least well understood. Chronicled in admirable detail by Simon Reynolds in his book Energy Flash, the breakbeat strain in the rave revolution is wide and deep. Taking just a couple more examples, Scott Hardkiss of the Hardkiss Brothers is another lesser known artist these days who had a big impact on the Chemical Brothers. His ‘Raincry’ as God Within — inspired by the breakbeat rave anthem, ‘Papua New Guinea,’ by the Future Sound of London — would earn him a remix commissioned by Weatherall for One Dove, his classic gorgeous ‘Psychic Masturbation’ mix of ‘White Love’ in 1993.

When Scott Hardkiss (real name Scott Friedel) died in 2013, Simons paid tribute to Scott and California’s desert rave scene on Twitter. The two outfits — Hardkiss and Dust — would share the same billing on Sandals’ ‘Feet’ single, with Scott’s ‘Wrong Side of Town’ remix as Next School rivaling the creativity and even in some ways outdoing the Dust Brothers remix. It was a friendly competition.

If the California and US connection with the Chemical Brothers still seems thin to some, then take another example: the Chemicals used Xpando and Eric Davenport’s Metro LA ‘To A Nation Rockin’’ not once but twice — on two separate mixed CDs, the excellent Live At the Heavenly Social Volume 1 (1996) and Brothers Gonna Work It Out (1998), both as peak moments in clear definitions of their DJ sensibilities.

***I would be remiss if I did not mention that John Kelley is my older brother. I have contemplated my objectivity and any conflict of interest in citing his Funky Desert Breaks success as part of the “breakbeat” story here. After a lot of thought, I have concluded I would be remiss as a historian if I did not mention his work here.

In addition, its importance has been pointed out to me personally by several key contributors in this history, including by Frankie Bones, Gavin Hardkiss and Wade Randolph Hampton. Additionally, both Reynolds and historian Michaelangelo Matos cite him. Nevertheless, again, I would include Funky Desert Breaks anyway based on the impact and quality of its musical programming and its cultural differentiation.

I will also mention here one more twist. Funky Desert Breaks had some degree of influence on the “Funky Breaks” genre label as well, which by the late ‘90s emerged as a distinction from the more British breakbeat sound. In some cases, it was used sometimes more derogatorily by journalists and artists to pigeonhole and even marginalize American producers and DJs who shared a heritage.

My general thought here is that “Big Beat” and “Funky Breaks” are both reductive and insufficient labels for what was a very diverse and expansive sound. In fact, “genres” do little to help anyone except journalists, newcomers, marketers, and promoters. It’s important for artists and DJs to identify a “style.” But it also can pigeonhole. Aesthetically speaking versus pragmatically, it’s about the music.