So You Said You Wanted to See the Future?

The emergence of the A.I. convergence holds infinite unknowns

“Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts... A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding...”

— From William Gibson’s classic cyberpunk novel, Neuromancer, 1984

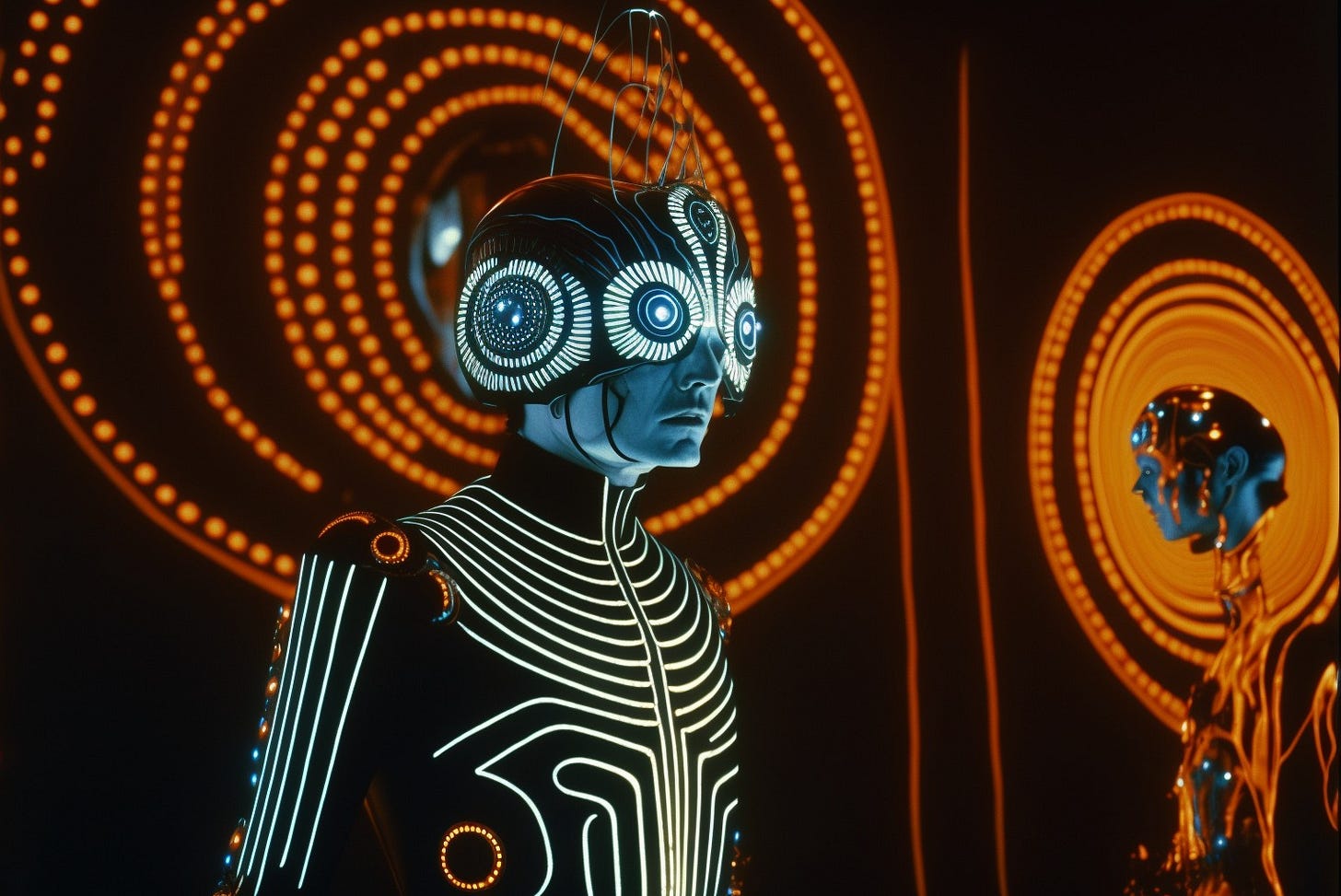

I remember the first time I watched Tron. It utterly blew me away and took me deep into a future I instinctively knew was not only coming but was already happening on some spiritual, mythical and psychological level. I was only seven at the time when I saw it in the movie theater. The year was 1982, and Steve Lisberger’s wild vision — much of it computer generated — mirrored my own sensations of playing the Atari 2600, going to video game arcades in malls, and puzzling over similar sci-fi mind warps like Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, which came out the same year.*

Strangely enough, both Tron and Blade Runner were commercial failures. But both films prefigured the world we live in today in startling ways — a world that profoundly reshaped our internal and external lives. The rave revolution was the musical, aural and hallucinatory echo of that change, a parallel universe that functioned as a kind of wild precognitive vision of the 21st century, with the last decade of the 20th serving as the optimistic glimmer at the tip of a massive wave that continues to accelerate and pound us into oblivion, or so it feels in the wake of what no one could imagine.

Well, that’s not necessarily accurate, because many artists did imagine a future speeding up beyond our control, whether we’re talking James Cameron’s Terminator or William Gibson’s Neuromancer. However, while the dark demons of human nature lurked in the android or artificial intelligence creations of those sci-fi worlds, I would say most people told themselves that these brilliant artworks, while diagnosing the dangers ahead, were tempered with the idea that such narrative visions would also enable us to avert the disasters found within. Were we not heeding the wisdom dramatized in these prophetic warnings?**

At least that’s how I once saw it. For I’ve always been fascinated by technology and the future. For one, my father was a systems designer who translated computer winds into flight path forecasts. So I grew up around “thinking machines” long before they were ubiquitous in most people’s pockets. For me, the last 100 years or so were a deep electronic dreamtime, a multi-cultural, multi-generational, multi-dimensional wave of the “Myth in the Machine,” a mirror of our deepest fears and dreams.

I don’t just mean that in terms of stories or entertainment experiences created with electronic and digital machines, whether we’re talking movies, video games or music. Nor do I mean just cyber warfare, attack drones and futuristic weaponry. I’m talking more specifically about the means and methods of our interface with the knowledge subsumed by the Machine — the algorithms that are growing in intelligence, and I would say effortless chicanery, and even on the flip side, dizzying beauty.

A lot of press this past year and now growing in fever, is on the rising tide of A.I. programs that are dazzling the public with their human-like capabilities. Much of the attention has been on OpenAI’s ChatGPT bot (which generates or augments textual communications) and the DALL-E image generator. But another program, Midjourney, is currently gripping imaginations with its explosive surrealism, crystallized by filmmaker Johnny Darrell’s experimentation with it, specifically his command: “production still from 1976 of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Tron.”

An interactive essay in The New York Times by director Frank Pavich is the best place to catch up with this phenomenon. Pavich, who made the documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune, a clever film about the Mexican filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky and his epic failed attempt to make a movie out of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi classic, marvels at Midjourney’s uncanny power — how a computer seems to now possess the hallucinatory and creative wizardry of a Herbert, a Jodorowsky, a Lisberger.

That idea that seeing is believing. And yet did we not hear it long ago? It all reminds me again of that precognitive blast that was the 1990s rave era. In many ways these A.I. programs reflect the earlier emergence of synthesizers and samplers. In fact, along with the films of Tron and Blade Runner, which inspired a generation of technologically minded or obsessed artists, including Gibson, many a 1990s electronica musician refracted those visions into sound waves.

Brave artists like Juan Atkins, The Aphex Twin, Daft Punk, Underworld, and The Future Sound of London were playing with programs and machines that hovered right on the edge of so-called A.I., samplers and synths spitting out warped sounds, many of them beautiful accidents, from gorgeous melodies (Underworld’s “Rez”), to strange new combinations of found and filmic conjurations (F.S.O.L.’s Lifeforms), to music video distortions of a monstrous psychosis (The Aphex Twin’s “Come to Daddy”); Chris Cunningham, one of the hippest music video directors of the time, actually worked with Gibson on a movie adaptation of Neuromancer, that like Jodorowsky’s Dune, never saw the light of day (ahem, Mr. Darrell, time for another one of your mind journeys with Midjourney?).

Like Pavich, I am both entranced and unnerved by Midjourney’s Lisberger-Jodorowsky mashup. Darrell, in his concise, clever mind-meld with the A.I. super consciousness of today’s Internet, has created a series of evocative and stunning images that open new doors of thought and reverie. Like the most beautiful and otherworldly compositions of the rave movement in the 1990s, it captures and liberates a human resonance with a techno clairvoyance.

Yet other memories also rush at me: a class I took in the 1990s about the history and future of computer science taught by Dr. Michael G. Dyer, a specialist in A.I. and neural networks. There I encountered lessons about Alan Turing’s Turing machines and the Turing test. I learned about motherboards, assembly code, compilers and operating systems — layers of computation that quasi-mirrored our own neural taxonomy in terms of cortical complexity layered on top of lower level reptilian functionality and emotional binaries.

Perhaps most importantly, I read about the theories of roboticist Hans Moravec, in particular his thought-provoking book Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence, which laid out two ends of the robot consciousness spectrum: one rooted in evolutionary biology and the motor-sensory systems required for any true android to negotiate the perception and movement through space and time; oppositional to that more physical progression was the school of pure logic, algorithmically driven digital models that reproduced human intelligence.

Somewhere in the middle is a singularity, a neural convergence of human and machine. Until machines can fully “live” experience through a motor-sensory mind and body — as a “robot” — in some ways, much faster, is the blossoming of the patterning and the analysis and recombination of patterns in the form of A.I. — a shared “Internet consciousness,” I would argue, if one were to step back and think about Midjourney’s almost mythological splendor, a “God machine” of our collective unconscious and a new Promethean fire, as it were.

Sucking in all the imagery that lives on servers and phones and computers from around the world, accreting nuances and faces and colors, and networking their associations in tags like “Jodorowsky” and “Tron” and “production stills,” an alchemical cauldron of our history and our hallucinations, Midjourney then regurgitates our future like a baby making sense of its surroundings.

One of Darrell’s other creative experiments with Midjourney, Snakes Are the Devil, is what Pavich describes as an “occult motorcycle flick.” Pavich is mesmerized by its imagery just as he was by Darrell’s co-imagined Tron sorcery. Here we get hints of George Lucas’ THX-1138 combined with Mad Max and Easy Rider, combined with what I perceive as Daft Punk’s Electroma, and J.R.R. Tolkien’s orcs perhaps, then crossed maybe with a rogues’ gallery from the cantina in Tatooine’s Mos Eisley.

Much how audio samplers work, Midjourney takes all of these ingredients and filters them through precise functions and algorithms that synthesize them into something wholly new. It’s what F.S.O.L.’s Garry Cobain once described as visual sampling. That is, visual processing has finally caught up with audio processing. What we may see next is something like visual samplers and visual synthesizers in the form of either hardware or software, but with a dizzying power, the A.I. working invisibly over the Internet with a sample library vaster than anything before it; then recombined with sound and music, whether in theaters or in glasses, animating dreams into reality.

But inherent in every techno fantasy is also the nightmarish, the darkness that inevitably comes with the brightness. I mostly remember rave as a wondrous thing. And yet, there was darkness. Whether in the misguided antics of the reckless. Or in the dystopian sounds and visions of its many underground artists. Perhaps that’s unsurprising. But at the time, its blast was so incandescent. Even with my own misgivings often on my mind, I still believed the future would be an overall improvement for humanity — a cyberspace of infinite creative possibility.

Even so, as trite as it might sound, it does seem like the future is still what we make of it. What Dr. Dyer made of it was something altogether different. Sitting in a room with other students, in the windowless bowels of a square building, on the last day he laid out for us what he believed would be the outcome of computer science. This is what he predicted: By the year 2050, most of society would be ensconced in virtual reality; during that time, robots would become as intelligent as humans; and by 2100, they would become our main means of war, labor and exploration, especially into outer space; borrowing heavily from Moravec’s projections, Dyer described how robots would possess distinct advantages, including the ability to instantly share their knowledge, reproduce at an industrial scale, endure interplanetary conditions…

Like a hive of robots communicating telepathically across solar systems, in what still feels like a message a la Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dyer’s rather dire message about 2101, still burns in my psyche as one of the most bizarre and arrogant visions of technological ambition I’ve ever had the privilege of encountering. At the end of his lecture, he said there were three possible conclusions to this story: 1.) humanity and our robots would achieve some kind of symbiotic co-living, but an asymmetrical arrangement where we would be like pets at best, 2.) the robots unfortunately would more likely annihilate us, even dissect us, and 3.) perhaps hopefully, they might just simply leave us one day to conquer the galaxy.

He then said, in all seriousness, “I didn’t say I am happy about this. But it’s going to happen.” Mind you, this was the same professor earlier that semester who one day asked the class how many people believed in God. I would say maybe 70 percent raised their hands. “That’s pathetic,” he said out loud. I didn’t raise my hand, but because I identified myself back then as agnostic, not because I adhered to any atheistic superiority complex. Personally, I was uncomfortable with any kind of zealotry, hardline atheism included, versus fervor, or…

Even faith? Now that’s a different question. I’m not sure I have faith in a Christian or Abrahamic version of “God” or the “Diety,” whatever those words may mean in any given time or context. Even so, I see the value in the moral vision of some of the world’s religions. For they are operating systems that help us function in very complicated and troubling contradictions. I put faith in human decency.

I have compassion for everyone in that lecture hall that day, including Dr. Dyer, as much as his faith in robots and computers struck me as borderline madness. I am grateful for what he taught me. I still do not agree with his self-belief in the ultimate glorification of a robot destiny, but his description of the 21st century woke me: artificial intelligence is no joke, and I have indeed sensed it long coming.

What worries me and uplifts me is one and the same: the creativity unlocked by machines. But what worries me more is the arrogance of we humans, the designers. The ultimate question comes down to our collective morality, our ability or inability to parse the truth, to honor or desecrate our democracy, and to imagine the future in a spirit of honesty and kindness and grace, versus deception and cruelty.

One of the core insights that Moravec’s Mind Children gave me was the connection between evolution and consciousness. He described the intelligence of bees and beasts, the wonder of what we so easily take for granted: the sensing and moving through oceans and landscapes in light and darkness. How did life emerge out of matter and nothingness? At a gentler remove, I realized that because we were conscious, so was the universe.***

So what will we teach our robots? Back in the rave days, not every DJ had a heart of equality or justice. As then, the Johnny Darrells of today will be at the forefront of our global myths and trajectory; mixing one composition with another, the kaleidoscopic weaving of rhythms and patterns bringing us once again to the revolutionary.

But A.I., our robot romance through our screens and mixed realities, now crests in front of us with unthinkable complexity. I recall once hearing techno out of speakers in the Mojave, and feeling as if I was standing at the base of a wave of a new humanity. We moved through it. And the dance floor of a dry lakebed helped our feet ride it.

The full moon shined bright. The desert air thrummed with the shapes and echoes of pure idealistic artistry. The argent orb circled beautifully, timeless, while the spinning earth curved underneath us. We could hear the future. And now, we can see it.

*A fun essay last year by Adam Nayman for The New York Times explored the cultural significance of films released in 1982, a remarkable year for the art form in terms of its popular impact. Films like Tron and Blade Runner are held as exemplars.

**A great primer on the sci-fi genre that speaks most to our near future — “cyberpunk” — is available on YouTube by Indigo Gaming. I highly recommend it. There are three parts. Part One is the most essential.

***The moonshot dream of humanity birthing robots with consciousness is still very much alive, and recently growing in its momentum. Read more about it here.