American Rave: A New Myth of Freedom

Looking back on my first history of machine music - "Little Brother"

And we can hear the god Pan piping through the doors of technology, his “laughter and music” speaking of strange dreams and mysterious realities. Playing with fierce abandon and then the most gentle feel, he draws us into the future with his new tricks. And both cruelly and kindly, he seems to whisper to us, “Whatever you dream, whatever you want.”

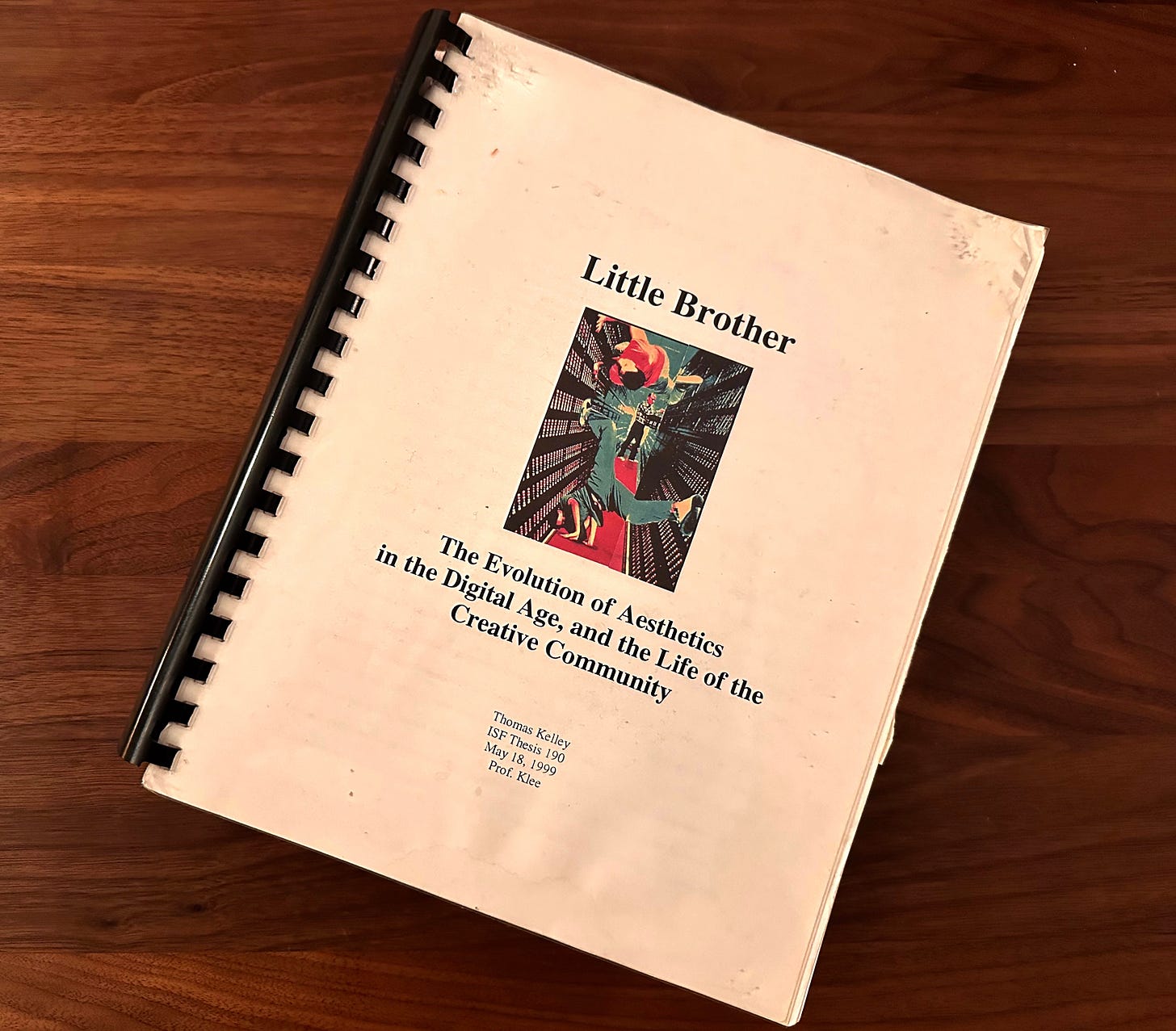

It’s about 200 pages or so. Its dog-chewed corners betray the years and neglect. Its artwork of two people breakdancing in a data center, defying gravity, gives a hint of the surrealistic ideas and perhaps the rambling daydreams inside. Its exalting title, “Little Brother: The Evolution of Aesthetics in the Digital Age, and the Life of the Creative Community,” is both accurate and a little esoteric.

At the bottom, it has a date: May 18, 1999. I remember getting it printed at a Kinkos that morning, just west of the UC Berkeley campus before dropping it off to Professor Earl Klee’s office, just a week or so before graduating with a degree in Interdisciplinary Studies Field: Technology and Culture, an emphasis I devised. For the last 24 years, I’ve occasionally thumbed through it; and for the last seven, this fever dream of an academic yet personal nature sat buried in storage.

I told myself long ago that I would return to it; I once believed I was telling a story that needed to be told, though I am no longer sure what the story is or how I feel about where it has gone because in many ways it is still unfolding. I have realized more recently that I only told maybe the first few chapters of a history I am still living. Truthfully though, I knew then, and I know now, that it’s a story as old as time.

And that still excites me. The quote I pulled at the top is actually the very end of the thesis. The allusion to Pan was a metaphoric device I threaded throughout its many insights and deep dives and tangential excursions. The god of mirth and music, of stirring the heart and passions, in the image of a half man, half goat, was an apt symbol in my mind for the transformations of the Digital Age. From my very first encounters with rave music and culture, its key was ecstasy, not the drug, but a Dionysian state, yet set within a highly rational and technological matrix. Often associated with the god of ecstasy, Dionysus, Pan is Yin to the cyborg Yang.

The work breaks down into three parts along with an introduction and conclusion, following a classical three-act narrative essay structure. The first act explores the history and potentialities of electronic dance music. The second act goes into the cultural wave of multimedia trends and their implications, from film to computer graphics to video games. The third act examines the social frameworks, and gravitational and anti-gravitational dynamics of ecstatic gatherings. A bonus (denouement) act deepens the main three by exploring technology’s ancient relationship to human consciousness and our creative intelligence.

The six sections are titled thusly:

1. Introduction: Pan and the Cyborg

2. “We are the Music Makers, and We are the Dreamers of the Dreams”

3. “They Step Out of Their Minds and Into the Computer World”

4. “And the You in You is the Same as the You in Me”

5. “Even the Stopped Clock Tells the Right Time Twice a Day”

6. Conclusion: Elder Brother and Little Brother

The Dionysian angle invoked in its pages is perhaps a tad overused to my mind now, though the ancient Greek god of wine and ecstasy still finds his way through human nature into our computer world. Friedrich Nietzsche is famous for his exhortations about the Dionysian and the Apollonian — the irrational and the rational.* Hence, it accommodated everything from caveman’s discovery of fire to dancing to art to microchips to AI and robots (Hans Moravec’s Mind Children for example).

But whether I had the diagnosis right or not, I was drawn back to this early attempt to make sense of our times by my revisits to the music of the 1990s. Searching again for the meaning and the magic inherent in its sound waves, it has brought me back to the hopes and fears of the artists, and of the human communities they lived within. That social context has been important in imparting why their artworks, why their music, still matters and will for all time — or at least that is my belief and intuition.**

As part of my Top 100 Electronica Albums of the 1990s project, I will start to excavate this earnest work from my youth, and try to separate its pretensions from the truths I was privileged to witness and consider. I have not actually read it since I authored it. Many of its ideas have stayed with me, if not in their original form; but others I have forgotten I am sure, and will loom like strangers at the side of the road.***

I will share my thoughts as I go on that journey, and start to piece together what is timeless and relevant in its pages. From there, I am hoping I will have a clearer sense of where Ghost Deep may go in the future, and what story must be told.

*The Dionysian and the Apollonian alludes to the Greek gods Dionysus and Apollo, the latter being the more cool-headed and composed deity, associated with light, healing and poetry. The slight problem with invoking their names is Western intellectualism’s over reliance on ancient Greek ideas in general and the degree Dionysus and Apollo are vogue symbols for the academic aesthete.

British writer Simon Reynolds used them in his intro to his free-ranging rave chronicle, Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. Originally published as Generation Ecstasy in 1998, it was one of the sources for my thesis, though my interest in Dionysus and Apollo came to me separately.

Rather hilariously, perhaps I was more subliminally influenced by the lyrics of Rush’s prog rock album Hemispheres, and the song ‘Cygnus X-1 Book II: Hemispheres’ more specifically, which name-checks Dionysus and Apollo too. Because I have two older brothers, and an older cousin who we spent hours with, reading comic books and drawing with, sessions set to Genesis, Led Zeppelin, The Police, and so forth, Hemispheres was seared into my psyche at age three or four. Ironically, Rush represents everything Reynolds hates I believe, and yet, Dionysus and Apollo symbolize different sides of the same coin, and have little to do with taste.

Almost entirely separately, and mostly because I have been fascinated with mythology all of my life, the image of Pan came to me while I was listening to Orbital’s ‘Planet of the Shapes.’ I paid homage to that vision in my tribute to their “Brown Album.” The first time I daydreamed to techno, Future Sound of London’s ‘Calcium’ inspired hallucinations of two fish jumping out of water and forming a Yin and Yang.

**A funny thing happened the day I wrote this post. As I drove into work I was listening to Lex Fridman’s podcast. He was interviewing MIT scientist Max Tegmark about the future of humanity and artificial intelligence — we are in a precarious moment. I was thinking as I listened how the potentialities of artificial intelligence and robot technology were a big influence on my thesis.

The upshot is that I argued that we needed to allow for some of the animal nature within us to express itself healthily through ecstatic experiences like rave to remind us and re-attach us to the greater truth that human nature cannot be simply overwritten by rational or scientific progress. In other words, we have to be willing to get a little crazy if we are to survive, to paraphrase British soul artist, Seal.

The funny thing is, Seal was greatly influenced by rave culture. My wife once disliked Seal — a funny story as to why, I can’t share here — but I have always admired his first album. It was a big deal in Europe especially. I remember watching the album’s videos on MTV Europe along with videos for the KLF my last summer living in Paris. While I titled this post “American Rave,” I am not interested in a solely American or patriotic history of house, techno, EDM, etc… The “Rave” part of the title actually alludes to British culture’s central importance to this global history.

Sure enough, in a little bit of coincidence, synchronicity, or a sign of the apocalypse, or salvation, or none of the above — perhaps just a blip in my own life matrix — The New York Times published an interview with Trevor Horn to their homepage the same day, who is one of the great masters and architects of electronic pop. I did not know this, but as I learned, he produced Seal’s ‘Crazy,’ the very song that popped in my head that morning as I contemplated the end of the world, and its liberation.

***The cover image of my thesis is of the electronica wizards, Plaid. I did a post on them in February, pulling out from my archives a story I did on them for Magnetic Magazine. I call the image out in the endnotes to the piece. To me, they sort of perfectly reflect and embody “Pan and the Cyborg,” today’s Yin and Yang.

Would it be possible for you to share your thesis with me? Sound fascinating!