This story on techno legends Plaid of Black Dog fame was written in September, 2011. After a very long pause, the group had returned with an innovative and otherworldly album, Scintilli. Known for creating some of electronic music’s warmest songs, their new direction evinced a confident step into colder yet no less vibrant territory.

Reworked with three key editorial strategies in mind, this new version of the story tweaks the title slightly, inserting an “Us” that shifts Plaid to a place of leadership at a time when our anxieties about the future are pronounced. It smooths the language in this direction overall. Second, having posted recently on The Black Dog’s Temple of Transparent Walls, I butterfly their history a lot more, revealing exactly why they are so important.

Third, I also brought this story back from my archives because of the recent breakthroughs in synthesized art via artificial intelligence. As original contributors to the “IDM” or Intelligent Dance Music genre — a deeply misapplied term for more pensive or cerebral electronic music — through Warp Records’ classic Artificial Intelligence compilation series, Plaid rightly fits the moment…*

“Hello? Can you hear me?”

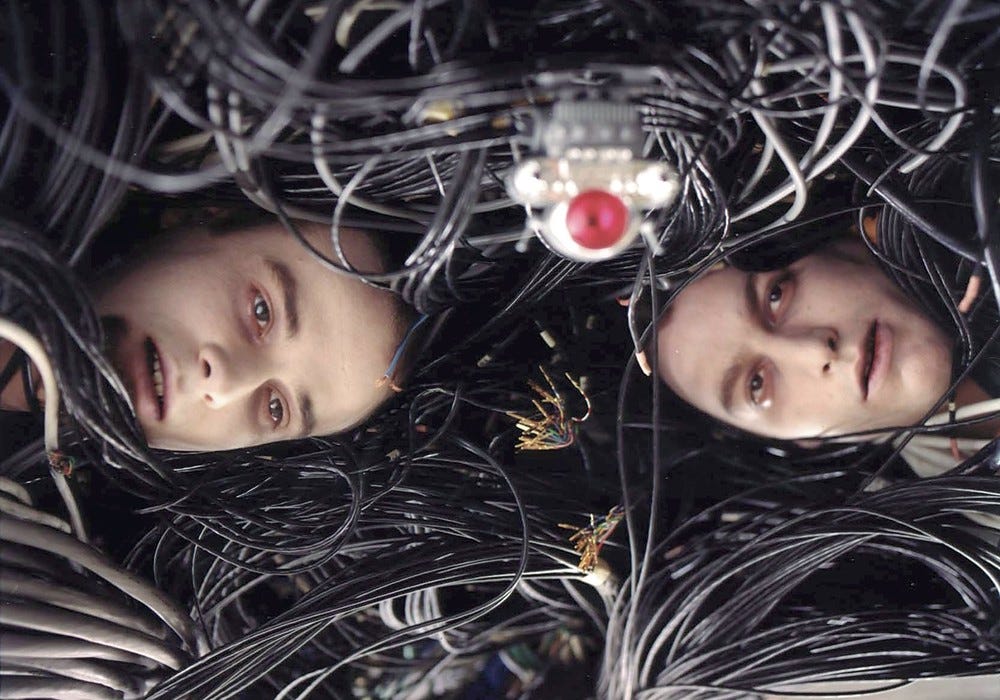

You can see Plaid on the other side, across thousands of miles from Los Angeles to London. Ed Handley is at a laptop and Andy Turner is peering into your screen. Warp Record’s press hand Helen Barrass is waving with a smile. But what you hear over the transom is a smear of digital noise modulating in musical tones like the glossolalia of some drunken robot.

You think for a moment that Plaid is playing their music live for you. That it’s their sonic greeting card a la Close Encounters of the Third Kind — the alien chords of our own everyday lives refracting underneath the surface of our machine world back out into our homes. But then Helen gives the thumbs down and we hang up.

Plop. Plop. Ed is calling back and this time you hear his friendly voice. “Sorry!” he says with a laugh. “We’ve been having issues with Skype all day.”

This is the world we live in. This is the world of Plaid. It’s a place of accelerating technology where people can peer around the planet and meet new faces online. It’s where robots can make sumptuous ramen in Tokyo. Or where computer calculations simulate the Big Bang down to an infinitesimal split second.

It’s also 2011, on the eve of Plaid’s stellar sixth album Scintilli, when Skype can still be as cranky and unpredictable as ever. That’s the unbroken nature of our electronic life: a never-ending series of blips and bits and zaps and taps from one screen to another. For the last eight years, Ed and Andy have been plowing on and experimenting in new pastures, pushing themselves as artists, working on film scores, coaxing machines, touring with a Javanese gamelan orchestra. One of British techno’s leading lights, they’ve reigned for years as the purveyors of quirk, unafraid of the fringe.

The name Scintilli can be translated from Latin as “I am many sparks.” But the album goes well beyond the poetic into the profoundly mysterious. It’s most stunning secret is that all of its beautiful, harmonic vocals are entirely synthetic, woven out of sine waves and Plaid’s own heartbreaking sense of song. No human vocal chords were abused or used in its making.

“It’s slightly eerie,” Ed admits with a chuckle. “It’s this computer expressing an emotion of some sort.”

Fortunately, it’s not really so eerie as it is magical. Take album closer ‘At Last,’ a gorgeous tempest of longing, its singing synths pulling at the heart strings and sweeping up the spirits. It’s one of Plaid’s best efforts in their over 20-year career. Or take the angelic ‘Founded,’ which quivers with a feminine grace that is truly haunting. You wouldn’t know either were purely electronic unless someone told you.

“We knew some people would object to it or find it creepy listening,” Ed says with a twinge of worry. “But we just thought it sounds good. It’s interesting. We’ve tried to learn about the human voice and what makes a voice a voice.”

The heavy vocal synthesis was a first for Plaid and given its success, they’ve upped the ante in humanizing machines. We knew computers could talk, but serenade? By using filter techniques and special software, Ed and Andy show they can, with style.

But ghosting the human voice is just one of many cool tricks on Scintilli. Plaid also used physics algorithms in real-time to generate various timbres in a shared virtual space. It’s a computer-intensive process that removed all the cages in their instrumental zoo.

“It works very well for bell-like sounds or percussive-struck sounds,” Ed explains. “It sounds acoustic-y. Effectively you have all these things resonating together inside the computer and affecting each other. So that was another road we went down. Just things to keep us interested, to keep the sparks going.”

Which brings us back to the name of their new album. “For me, it relates slightly to the sensation of listening to music,” Ed muses. “Sometimes you can almost sense, when something’s good, you get a spark or you get some sparks happening. Conceptually that’s what it’s about: the spark of life, the spark of creativity.”

Plaid has gone far afield to find some of those sparks. To some fans, they dropped off the face of the earth following their 2003 album, Spokes. Except the duo were actually hard at work on other creative endeavors. They collaborated with longtime friend and video artist Bob Jaroc on the audio-visual DVD Greedy Baby. They hooked up with LA transplant and Tokyo filmmaker Michael Arias, scoring his movie Heaven’s Door and the anime feature Tekkon Kinkreet; the latter made especially good use of Plaid’s sensitive aesthetic to help tell a story about orphans battling the yakuza.

Ed and Andy even collaborated with inventor Felix Thorn, who designs robotic instruments that play themselves. “It’s basically deconstructed pianos with phono lines attached, which make a crazy kind of dance music,” Ed explains. “We played a little festival up in the countryside and came across the machines in a room and were sort of wowed by them. So we approached Felix and said we’d like to do something with him and he was up for it.”

But Plaid’s recent experiments with Felix’s Machines don’t mean they’re strict futurists. The past speaks to them loudly. The Javanese ensemble of xylophones, drums and gongs known as gamelan also grabbed their attention. Gamelan music famously pricked the imagination of French composer Claude Debussy in 1889 at the Paris World Expo, inspiring him to craft ornamental impressionism like Clair de Lune, which in turn inspired other currents that helped seed modern electronic music in the 1900s. It was at a music festival in London’s South Bank that turned Plaid onto the same traditional sounds.

“That’s been really stimulating because it’s a completely different tuning system,” Ed says. “Working with these players generally has been very eye-opening. The beauty of Javanese music is it’s very repetitive, very trance-y. It relates to dance music quite well. It has the same aim.”

The Scintilli track ‘Craft Nine’ carries the shimmery vibes of gamelan’s bright clangs and twinkling percussion, while ‘Somnl’ ricochets to banging bells, sprinkling its fairy dust over snarling dubstep bass. As Ed points out, Plaid has always gravitated toward steel drums and chimes. But there’s a finer balance on the new album that gives their music a more open, unfussed elan.

“It was the idea of a looseness and a sort of lack of complexity which we got really from working with the gamelan,” Ed explains. “And the idea of restraint, of not layering on too many influences, because in some of our previous material, we had gone a bit overboard in layering and layering synths. And this one we tried to hold it back.”

That increased dynamism through minimalism feels like a real turn in Plaid’s musical DNA, folding in on its double helix. Changes in their personal lives also helped usher in the calm. Andy is now a father and Ed moved back to rural Suffolk, where the two friends met as teenagers.

“It definitely has an effect on music making,” Ed reasons. “If anything it has made me want even less…to sort of go to a minimal sound in a way because there is so much space and peace there. It takes less to do more, if you know what I mean.”

You can hear this unhurried ease in album opener ‘Missing,’ which gently waltzes to harp synths and child-like chants. Even on the rambunctious ‘Unbank,’ the confident, almost lazy rumble of heavy metal riffs a la Van Halen and Muse ooze under a cloud of dusky gasps. ‘Tender Hooks’ follows similarly in a dreamy echo, falling like timed water drops in a crystal cave.

This kind of bucolic ornamentalism can be found throughout Plaid’s work, as far back as their earliest days as part of The Black Dog collective. Classics like ‘The Crete That Crete Made,’ ‘Rainbow Bridge,’ ‘Olivine’ and ‘Further Harm’ have belonged as much to outdoor sunsets as cyber cityscapes. Even ‘Buddy’ from 1999’s Rest Proof Clockwork migrates in this quieter direction. It is perhaps their most eccentric take on this theme, an easy-as-she-goes canoe trip down a sleepy underground river.

But that’s only one side of Plaid, which fans and newcomers will happily embrace on Scintilli. The other side is dance rhythms that play an equal role on this return. ‘Talk to Us’ jams to wheezing synths and lashing, stabbing bass, while ‘Thank’ then whirls and whips on a broken sidewalk of slamming beats. It’s the same old freak-out genius Plaid originally burnished their fame on, from the winding grooves of ‘Psil-Coysin’ on The Black Dog’s Spanners to the swimming attacks of 1995’s ‘Angry Dolphin’ to the whooshing marionette grooves of ‘Abla Eedio,’ on 1997’s Not For Threes.

“I think the idea of a dance is still really important to us and it’s sort of where we’re going,” Ed says with pride. “I don’t think we’ll ever get rid of this sense of rhythm and a rhythm you can dance to. The process of hearing music is like a dance. Internally, you’re dancing. Most music to me, anyhow, feels that way, it’s about a sort of movement.”

Where does that mutual commitment to motion come from? When Ed and Andy first met in the ’80s, they bonded over a mutual love of hip hop, techno and breakdancing. To this day, while mostly retired from dangerous moves, they continue to be inspired by the acrobatic, angular, circular grace of that now timeless street style.

“We still try to keep up with breaking,” Ed says, his voice lifting with more excitement as he gets into their old pastime. “I watch the various competitions. For me it’s lovely seeing the balance between the gymnastic, athletic style and the sort of footwork styles. It’s incredible how sophisticated it is now. It’s sort of way beyond Olympic gymnastics. Some of the stuff they can do is just phenomenal, the stuff we used to dream about really, these weird combinations of flares crossed with windmills with halos with fusion moves.”

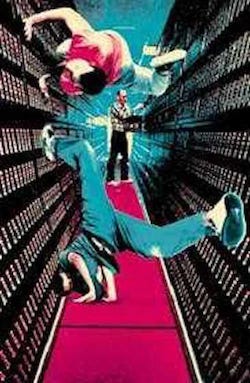

Those moves continue to inspire Plaid’s music, which sounds exactly like Ed’s descriptions. Perhaps the most telling image of Ed and Andy accompanied the release of Not For Threes. It showed how playful the pair really are: a photoshopped image of them breakdancing against the force of gravity, vertical in mid-motion, on the shelves of a staid mid-20th century library or data center.**

“When we were doing it, it was, ‘Can you do a windmill?’” Ed recalls of their more youthful days. “And then, ‘Can you do a one-handed windmill?’ But now it’s not really about that. It’s about how you go from one move to another and just amazing balance as well. A lot of the freezes people do is just mind-blowing. I still love it. It’s one of my favorite things really. I don’t really do it anymore, unless it’s with Andy.”

Andy has been mostly absent from our Skype meld. He’s been passing through here and there. The video screen is dead but you can hear him closing doors, moving this way and that. As Ed explains, Andy’s a busy dad now, and one imagines he savors any downtime he can get. But you can also picture him spinning behind Ed as he talks.

When asked what their favorite dance styles were, Ed offers a perfect portrait of their symbiotic artistry: “Andy was a good windmiller,” he says. “I was really more of a popper more than anything. I enjoyed locking, which is really tensing up all your muscles, like you’re having a fit. That was always my thing.”

Like their dancing, Plaid’s music is a unique combination of the tense and the whimsical, the earthbound and the airborne. But going deeper, there’s an upbeat melancholy that holds Plaid’s center of gravity. It’s at once up and down but always emanating from an optimistic core.

In 1992, Ed wrote one of the most dearly beloved techno tracks of all time, contributing the song ‘Norte Route’ to Carl Craig’s Intergalactic Beats compilation album. It’s a windswept surf through outer space, its wooden drums clocking the seconds of a cosmic breakthrough. (In a blast from the past, another storied act, Global Communication, recently used it as a prized highlight on their double-mix album from 2011, Back in the Box.)

Ed and Andy made their first big statement as Plaid with their debut album, 1991’s Mbuki Mvuki, which included breaks and Detroit techno-influenced classics like ‘Link’ and ‘Anything,’ while showing off their more playful and eclectic side on the ‘Scoobs in Columbia’ classic, sampling and cutting up Latin hollers, horns, guitars and rhythms to funky effect. As two-thirds of The Black Dog Towers team and as Warp artists on the IDM vanguard, their contributions to Bytes and Spanners, and on General Production Recording’s Temple of Transparent Walls (misprinted as Balls), won them many enduring admirers, including non other than Bjork.

In the mid-1990s, Bjork enlisted The Black Dog and then Plaid for various projects, starting with remixes (her Bjork Bitten By Black Dog promo featuring ‘Come to Me’ is especially magical) and including as part of her live band. In turn, you can her Bjork’s influence on Plaid’s many vocal works, including perhaps even Scintilli. The ghost of her siren-song mystic synthesis inspired other vocalist collaborations, like Plaid’s ‘Rakimou’ and ‘Ladyburst’ with Mara Carlyle. Bjork features on Plaid’s ‘Lilith.’ But Nicolette of Massive Attack and Shut Up & Dance fame also influenced Plaid. Recruiting them to co-produce parts of her second album, her Shirley Bassey tonalities and elastic range still echo in Plaid’s jazzier, warmer affairs.

It’s that attraction to the human as much as the machine, that still stands Plaid out as one of techno’s most humanistic projects, one that has had a chameleonic longevity spanning decades. Their extensive remix catalog, which includes the Plaid stamp on unique artistic voices and spirits, from Bjork and Nicolette to Grand Master Flash and the Furious Five and Studio Pressure to more technoid brethren like Brian Dougans’ Humanoid and their long friend, LA’s techno son, John Tejada, is captured on the excellent Parts in the Post remix compilation and the non-profit Stem Sell.

Like tricksters constantly playing a game of telephone with the Machine — the computer, synthesizers and samplers, artificial intelligence vocal software, robots — Plaid have managed to sync and align the human in a kind of perfect breaking flow that whirls and whips into the unknown and back again. As a duo, this is part of the Plaid dance that seems to keep the waves coming. Andy, a presence versus an absence in our conversation, in some ways represents that other side, the one unspoken, a continent of endless discovery. You can even see this philosophy imprinted in the Plaid logo and many of their album covers. Circles pronounce prominent interests in the supple and the infinite.

The cover of their 2001 album, Double Figure, is a good example. It has a Yin / Yang quality to it, the Taoistic dynamics of a water drop splashing upward toward a mythic seahorse with what looks like a rooster bending at the bottom, and enclosed polygons in between. The Tao has always evoked two fish swimming toward and around each other, chasing tails, like the moon or two planets spinning on the same axis. The Not For Threes cover has that sweep. Even the cover of Scintilli follows the same clock rotation, with its letters wrapping and folding in a three-dimensional swirl.

Unabashedly electronic, yet deeply human, Plaid continue to cut a path that shows us how new technologies like artificial intelligence and old sounds like the gamelan might enlighten the world in the right hands — hands and feet that grasp and turn. It’s the eternal dance. Breaking, fusing, windmilling, pop locking, spinning, the ebb and the flow — the future as fluid forever.

All these years later, these mysterious waves of Plaid are still bringing people together, from old peers to new pals. Ed says he generally doesn’t mind looking back. He realizes that most of the younger generation have never heard gems like his ‘Norte Route’ or ‘Angry Dolphin’ from the 1990s rave heyday. He also recognizes Plaid is just one of many sparks from the creative supernova of techno’s first golden age.

“You were hearing so many things you’d never really heard before,” Ed says fondly of that formative time. “A lot of the characters involved were really decent and were just about making music. There was no idea really of making lots of money from it or anything. These were just heartfelt tracks that were coming out.”

He pauses for a moment, as if his memory is probing, finding a deeper frequency that runs through the years and into the infinite, one just on the edge of words and song, like the halos and fusion moves from one era to another. “You can still hear the intention behind them,” he says slowly. “You can hear the meaning.”

This grace is what will survive when it comes to electronica’s hectic evolution. Listening to Scintilli, a genuine humanity always shines back through. Maybe Plaid is teaching robots how to sing and how to dream. On ‘Upgrade,’ the bass skids like that drunken Skype burble, echoing a future of unlimited possibility.***

But listening carefully from the other side, from the past back to the future, Scintilli is no doubt music made for and by humans. The heart-aching beauty of something like ‘At Last’ is calling out, asking us to wonder about techno’s ultimate purpose.

Plop. Plop. Pick up the line, it seems to say across time. Feel the sparks fly. And maybe someday, one wonders, a tearful robot may hear us and reply.

“Thank you. We needed that. Welcome back.”

*With the advent of new A.I. innovations like ChatGPT, Midjourney, and soon their more overt implementation in search platforms like Bing and Bard, the role of technology in everyday life is growing ever more pronounced.

Plaid has never shied away from trying out and using new technologies, which I think makes them a valuable lens by which to understand the present and future, as well as the past, as fears and hopes grow around yet another wave of techno-social change.

**As part of the promotion of Plaid, post Black Dog, Warp Records released a particularly powerful image of Ed and Andy in 1997 breakdancing inside a row of stacked books or data drives (hard to tell which, though I vote for the latter). This is the best surviving copy of the image I could find online…

***Plaid have in fact continued to hit their stride after their fuller return with Scintilli. They have released five albums since, almost one every two or three years, along with E.P.’s and a Peel Session. Particular standouts are some of their best albums yet, including 2019’s Polymer and 2022’s Feorm Falorx.